Shai Held

The following excerpt is adapted with permission from Shai Held, “‘With Fists Flailing at the Gates of Heaven’:1 Wrestling with Psalm 88, A Psalm for Chronic Illness,” in A New Song: Biblical Hebrew Poetry as Jewish and Christian Scripture, ed. Stephen D. Campbell, Richard G. Rohlfing Jr., and Richard S. Briggs (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2023), 142–55.

Psalm 88 is undoubtedly one of the darkest of the psalms. One scholar labels it “the most desperate of all laments”;2 another writer asserts that it presents “a wintry landscape of unrelieved bleakness”;3 and a third insists that the text is “unrelieved by a single ray of comfort or hope.”4 Yet Psalm 88 is even bleaker and more desolate than most scholars seem to realize—or allow.5

In a recent essay David Howard, Jr. goes so far as to refer to Psalm 88 as “the mother of all laments”6 and in terms of the bold and unapologetic voice it gives to human grief and suffering, it may well be. Yet (as Howard himself acknowledges) Psalm 88 stands out as much (if not more) for how it differs from other psalms of lament as for how it typifies them. In order to get at the spirituality of the psalm, we need to take careful stock of these divergences from the standard form.

Recall Gunkel’s enumeration of the common features of lament.7 Among the most significant are an invocation; a complaint or characterization of the psalmist’s predicament; an appeal for help; appeals and curses against enemies (sometimes coupled with wishes for the faithful); motivations for divine intervention; expressions of trust; articulation of certainty of being heard; and a vow of future action. Now, a psalm need not contain all of these elements in order to be considered a lament, but it is nevertheless striking how many are missing from Psalm 88. The psalm begins with an invocation (v. 2) and continues with an appeal to be heard (v. 3).8 Most of the rest of the psalm is the complaint, though one could argue that the rhetorical questions of verses 11–13 provide motivations for intervention. Psalm 88 contains no explicit appeal for help,9 which Gunkel considered the most important element of the psalms of lament.10 The psalm contains no expression of trust11 and does not give voice to a certainty of being heard, nor does the psalmist take a vow to praise God when he is saved. Most crucially, the core arc of the lament, the movement from lament to praise, is entirely absent from the psalm. The psalm ends where it lives: in darkness.

Consider, too, how much of what is conventionally said of psalms of lament does not apply to Psalm 88. Richard Clifford, for example, writes that laments could more aptly be referred to as petitions, “since [their] purpose is to persuade God to rescue the psalmist.”12 In Psalm 88, however, petition is marginal, if it is present all.13 If anything, the psalm is relentlessly focused on the ways that God has failed to respond to the psalmist’s repeated petitions for deliverance. Clifford adds that “The lament offers oppressed and troubled individuals a means of unburdening themselves before God and receiving an assurance.”14 One who recites Psalm 88 may well unburden herself, yet she will find no assurance at all in the psalm. Clifford further avers that “The lament enables the worshiper to face threats bravely and learn to trust in God.”15 Yet, as we will see, it is far from clear that Psalm 88 evinces much by way of trust. On the contrary, the worshiper who engaged with this psalm may well hear only that the psalmist’s trust in God has yielded nothing but vexation and frustration.

Emphasizing the importance of the waw adversative in psalms of lament, Claus Westermann notes that it serves to introduce a turning point where lamentation gives way to confession of trust or assurance of being heard. “The ‘but,’ ” Westermann writes, “designates the transition from petition to praise.”16 Yet in Psalm 88 the waw does quite the opposite: it leads into one final outpouring of lament, this one “all the more insistent on YHWH’s rejection of the psalmist in spite of his constant pleading”:17 “But as for me, I cry out to you . . . . Why, O Lord, do you spurn me?” (vv. 14–15). Westermann maintains that “In the Psalms of the O.T. there is no, or almost no, such thing as ‘mere’ lament and petition. . . . The cry to God is always underway from supplication to praise.”18 But as its subversive use of the waw adversative shows, Psalm 88 constitutes a dramatic (and deliberate!) exception to Westermann’s rule.19

Psalm 88 thus essentially strips away the glimmers of hope we conventionally find in the psalms of lament. Just how deep is the rupture between the psalmist and God? An array of scholars finds in verse 2a’s אֱלֹהֵי יְשׁוּעָתִי, “God of my salvation,” a hint of hope and even praise. Thus Marvin Tate, for example, writes that “Praise seems far away from Psalm 88, but in reality it is not; it even glimmers in the opening affirmation: ‘YHWH, the God of my salvation.’”20 Others suggest emending the text so that it reads אלהי שועתי, “My God, I cried out.”21 The emendation helps establish parallelism in an otherwise difficult verse,22 but to the best of my knowledge there are no manuscript variants to support it. Moreover, if one thinks that אלהי ישועתי introduces a glimmer of hope into a very dark psalm, emending the text eliminates that sole glimmer and “the only redeeming expectation present in the psalm is turned into yet another plea to God.”23

I would suggest we consider a third alternative, namely that the psalmist does indeed refer to YHWH as “God of my salvation,” but that he does so at least somewhat ironically.24 After all, the God to whom he calls has been anything but a God of deliverance to him. If the notion that the psalmist is speaking ironically seems far-fetched, consider what follows: 1) the declaration in verse 4, שָׂבְעָה בְרָעוֹת נַפְשִׁי, I am sated with misfortunes,” is clearly ironic, since it is usually some form of goodness or blessing that “sates” the psalmist (see, e.g., Ps 63:6: “I am sated as with a rich feast”; and Ps 65:5: “May we be sated with the blessings of Your house”).25 To announce oneself sated with sorrows is obviously to speak in a highly ironic way. 2) The opening of verse 6, בַּמֵּתִים חָפְשִׁי, is extremely elusive. But some have suggested that the psalmist says this ironically, since he is “free” only “from everything that makes life meaningful and enjoyable; free to be as good as dead.”26 3) The use of the word סָמְכָה in the accusation of verse 8, עָלַי סָמְכָה חֲמָתֶךָ, “Your fury lies heavy upon me,” is jarring, since the root ס־מ־כ often calls to mind God’s faithful and steadfast support. These three examples suggest that the psalmist is no stranger to irony,27 and that he is unafraid to employ it in direct address of God. Whether God is really the God of “my salvation” is one of the questions that most agonizes him.

As these examples of irony indicate, the psalmist is unabashed in calling God to account. In a subtle way the psalmist says so explicitly. Reminding God that he has been praying constantly, incessantly,28 the psalmist declares בַבֹּקֶר תְּפִלָּתִי תְקַדְּמֶךָּ, which NJPS renders as “Each morning, my prayer greets you” (v. 14). The Hebrew תְקַדְּמֶךָּ can indeed be taken neutrally, but it can also suggest hostility and confrontation,29 as in Psalm 17:13: קוּמָה יהוה קַדְּמָה פָנָיו, “Rise up, O Lord, confront them!” I wonder whether that meaning is at least hinted at here as well: the psalmist has not uttered gentle hymns each day but has accosted God and pleaded his case with passion (and, perhaps, with no small degree of fury too). In a similar vein, Tate points out that the reference to morning contains a note of bitterness, since morning was considered the time to expect God’s help, help that in the psalmist’s case never did come.30

The strife between the psalmist and God is brought to the surface by another anomalous feature of the text. In psalms of lament we typically expect to encounter three parties: the psalmist, the enemies who persecute him, and the God he prays will save him. But Psalm 88 lacks any mention at all of human enemies, and one wonders whether that is because God has been cast in the role of the enemy instead. After all, it is God who is declared responsible—again and again and again—for the psalmist’s woes.31

Why is the breach between the psalmist and God so profound? Psalms of lament depend on a longstanding relationship with God; part of what animates them is the fact that the psalmists have a past with God to draw on. Although the psalmists find themselves mired in affliction, as a rule they are confident—and they know from experience—that the God to whom they appeal is faithful and steadfast. As the psalmist’s situation was once, so it can be again.

With this in mind, I would argue that the key word of the psalm has been overlooked (or at least underappreciated) by most commentators. Towards the end of the psalm, we learn something crucial about the psalmist’s life, something that forces us to see his misery in a radically new light. The psalmist’s present predicament is no anomaly for him; he is not wrestling with a new, unforeseen torment after a lifetime of wellbeing and contentment. On the contrary, he has been גֹוֵעַ מִנֹּעַר, “dying since youth,” that is, he has been forced to endure lifelong, crushing chronic illness.32 It is one thing to struggle with acute illness after a lifetime of health; it is quite another to grapple with a debilitating illness of long-standing. In theological terms, the psalmist’s problem is not that God seems to have suddenly abandoned him after long years of protecting him but rather that God forsook him long ago and that his life has been defined by that forsakenness.

Imagine a strong, loving, durable marriage that suddenly encounters difficult times and then compare it to a lengthy marriage that has been fractured for decades. It is obviously far more difficult to find a basis for hope in the second scenario than in the first. The psalmist’s relationship with God is more akin to an irreparably broken marriage than to a fundamentally solid one that has suddenly reached an impasse. It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this distinction. The psalmist in Psalm 88 has no personal past to which he can turn for hope and assurance. Even if we take his invocation of God as “the God of my salvation” at face value, the psalm unfolds in a way that mimics the way his life has unfolded: by the time we have encountered the endless litany of suffering and woe, the “God of my salvation” is little more than a distant and faded memory.33 For all intents and purposes, the only God this psalmist knows is a God of inexplicable wrath and abandonment.

The fact that we learn of the chronic nature of the psalmist’s suffering only near the conclusion of the psalm is jarring, even devastating. Perhaps we had held out hope for him—and by extension for ourselves; perhaps we were put off by the unrelenting nature of his complaint— surely life is not all bleakness and heartache; and then it hits us: life has been this way for as long as the psalmist can remember. His lament reflects the reality of his life: the misery and the suffering just go on and on. At the end of the tunnel there is . . . only more darkness.

It is worth noting how at the opening of each of the three sections of the psalm (verses 2–10a, 10b–13, 14–19), the divine name moves backward one place in the sequence of words. Thus, verse 2 begins with יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵי יְשׁוּעָתִי (first place); verse 10b with קְרָאתִיךָ יְהוָה (second place); and verse 14 with וַאֲנִי אֵלֶיךָ יְהוָה שִׁוַּעְתִּי (third place). As Erich Zenger insightfully explains, “The invocation presented in all three sections with the Tetragrammaton underscores the intensifying drama. . . . The hiding of God’s face that is complained of in verse 15 is literally put into words.”34 The more the psalmist prays, the further away God seems to be. Subtly but palpably, God’s abandonment of the psalmist is rendered concrete.

Strikingly, as the psalm progresses the psalmist effectively ceases to petition God. In what appears to be the psalm’s one and only explicit petition, in verse 3 the psalmist implores God: תָּבוֹא לְפָנֶיךָ תְּפִלָּתִי הַטֵּה־אָזְנְךָ לְרִנָּתִי, which NJPS renders as “Let my prayer reach You, incline Your ear to my cry.”35 It’s worth noting that verse 3 could be interpreted as a memory of past cries for help, mentioned in verse 2, rather than a present-day prayer, in which case the psalm would be completely devoid of petition.36 But by the time we get to verse 10, קְרָאתִיךָ יהוה בְּכָל־יוֹם, “I call to You, O Lord, each day,” more than petitioning, the psalmist is complaining about God’s stubborn inaction in the face of his own constant outpouring. The same applies to verse 14, וַאֲנִי אֵלֶיךָ יְהוָה שִׁוַּעְתִּי, “But as for me, I cry out to You, O Lord.” The psalmist is praying but he is not really petitioning so much as remembering—and reminding God—just how fruitless his long history of petition has been.

When the psalmist unleashes a torrent of rhetorical questions—“Do You work wonders for the dead? Do the shades rise to praise you? . . .” (vv. 11–13)—there is an element of petition to his words.37 The psalmist reminds God of the desperate urgency of his plight; if God wants his praise, God ought to understand that they are both running out of time. Yet to the extent that we interpret the psalmist’s questions as petitions, we should note that they are only implicit, indirect ones. It’s as if the psalmist has been so hurt and so disappointed that he can’t quite bring himself to petition God directly. The psalmist still needs help, so he gestures at pleading for salvation; but he’s also exhausted and crushed, so much the most he can do is remind God of petitions past and hurl questions at God that (arguably) intimate a present-day request. As Artur Weiser astutely observes, the psalmist “cannot even nerve himself to make any more direct requests for God’s help.”38 As for Job, so for the psalmist speaking does not help, but silence does not seem like a live option either: “If I speak, my pain is not assuaged; and if I forbear, how much of it leaves me?” (Job 16:6).

In a number of psalms of lament, the pain of being distant from God comes coupled with the agony of social isolation. The author of Psalm 42–43, for example, complains of being far from God and God’s temple but also misses the “festive throng” with whom he once walked in pilgrimage to Jerusalem (42:5); for him the sound of “joyous shouts of praise” has been replaced by the very different sound of “breakers and billows” sweeping over him (42:5, 8). For the psalmists, to be separated from God is to be separated also from God’s people.

Psalm 88 picks up on this theme and forcefully amplifies it. Not only has God unleashed God’s fury on the psalmist, but God has turned his friends—those who might have comforted him in his affliction—away from him, making him “repulsive” in their eyes (88:9). Those of us stricken with chronic illness know this frustration well: just when we need our friends most, they move on, forgetting the depth of our suffering, or perhaps, being frightened off by it (it does not seem much of a stretch to connect “repulsion” at illness with fear of it). More than that, the psalmist is shut in, feeling “imprisoned” by his body and abandoned by his companions. He is desolated by isolation.39

Where does the psalm leave us? The concluding verse remains something of a crux; it is difficult to know how to punctuate, let alone translate, it: הִרְחַקְתָּ מִמֶּנִּי אֹהֵב וָרֵעַ מְיֻדָּעַי מַחְשָׁךְ. The two final words might mean “my companions are in darkness” (NRSV) or “darkness is my closest friend” (NIV). Although I cannot make a compelling grammatical argument for it, I am drawn to the suggestion that we take the Hebrew to be interrupted after מְיֻדָּעַי, thus yielding: “You have caused lover and friend to shun me, my companions (you have caused to shun me)—darkness!”40 However we render the final phrase, the key point is that “Like it or not, forsakenness has the last word in Psalm 88.”41

What are we to make of this agonized prayer? Many writers insist that despite its grave doubt and burning anger, Psalm 88 is a document of great, even heroic faith. Kathleen Harmon, for example, writes that “While Psalm 88 may appear to indicate loss of faith . . . it actually does quite the opposite. The very act of speaking to God when God does not respond is an expression of profound faith. The person who no longer believes would simply walk away.”42 This is true as far as it goes, but it raises a question rarely if ever asked by scholars: just what does the psalmist’s “faith” consist of? Faith is, obviously, a word that means many things to many people, and I wonder how helpful it is to use it without really attempting to flesh out what we mean by it. To be more concrete: the psalmist may still have something we would call “faith” in God, but does he still trust in God? Does he see God as reliable and faithful?43 Can there be genuine faith without trust? The answer may well be yes, but it seems odd not even to consider the question. More fundamentally, at this late date does he still harbor hope that God will intervene to save him?44 Attempting to give some substance to the psalmist’s faith, Leonard Maré writes that “He still speaks to God, he affirms his relationship (God of my salvation), he believes praise is the norm and wishes to return to it, he acknowledges YHWH’s attributes (faithful love, faithfulness, righteousness, wonderful works).”45 Yet Maré’s suggestion requires significant nuancing. It is certainly true that the psalmist still addresses God and that he wishes that he could return to a life dedicated to praising God. But as we’ve seen, it is not clear that the psalmist unequivocally “affirms” his relationship with God (irony is in part an expression of equivocation); he may dream of being restored to a life of praise, but it seems unlikely that he trusts that this dream will be fulfilled; and he does mention God’s attributes, but only as a distant memory, and in the context of anticipating soon being fully and finally cut off from them.46 We will need to work harder to try and understand just what we mean when we speak of the psalmist’s enduring “faith.”47

Given the intensity and duration of the psalmist’s suffering, given how many desperate prayers have gone unanswered; it is a wonder that he goes on praying at all.48 Robert Culley wonders why the psalmist would “offer such a prayer if there is no hope for an answer or if there is no hope of persuading YHWH to rescue?”49 Whether the psalmist is totally devoid of hope or only mostly so I cannot answer,50 but in any event I think the answer to Culley’s question lies elsewhere. Despite his anger and disappointment, the psalmist refuses to sever his connection with God. Or perhaps, as he himself sees the situation, he refuses to allow God to sever God’s connection to him. God may hide God’s face, but the psalmist will go right on talking because otherwise he will be utterly alone. In a sense, the psalmist’s ceaseless talking to God keeps God “present” even as the psalmist complains of God’s absence.

There is, of course, a theological dimension of all this. Walter Brueggemann movingly maintains that the psalmist prays because praying to YHWH is simply what Israel does: “To be Israel is to address God, even in God’s unresponsive absence.”51 Israel may feel abandoned, betrayed, abused but Israel will not be silence(d). As Brueggemann writes, “The faith of Israel is like that. The failure of God to respond . . . leads to more intense address. This psalm, like the faith of Israel, is utterly contained in the notion that . . . YHWH must be addressed, even if YHWH never answers.”52

But there is also an existential dimension to all this that we must not overlook. The psalmist has endured unspeakable suffering. As if the sheer reality of enervating illness has not been enough, he has been forced to confront persistent feelings of abandonment—both the God to whom he turned for salvation and the friends to whom he looked for solace have effectively left him for dead. But he is not dead, and he needs to be heard. To give voice to his suffering—physical, emotional, and spiritual—is to reclaim his own dignity.

An (Ambivalent) Theological Postscript

The author of Psalm 88 assumes that a very active providential hand is at work in his life; as Carleen Mandolfo puts it, “The supplicant of Psalm 88 never questions God’s active omnipotence in the affairs of the world.”53 God (alone) is the source of his woe and God (alone) can be the source of his deliverance.

For many modern readers (and, frankly, for me too), all this no doubt raises an array of difficult questions: What kind of God do we need to believe in, and what notion, if any, of divine providence do we need to have, in order to utter these psalms with integrity? If we don’t believe that God actively runs the world, or even if we don’t believe that God runs the world in quite so micromanaging a way, can the psalms of lament still have a place in our religious lives?

The psalmists cry out to God because they believe that God can relieve their suffering; they don’t just want to be heard, they want to be answered—and saved. The primary purpose of lament in biblical times was not catharsis but salvation. This leads some Bible scholars to assert that “Prayers of sorrow and complaint that expect no concrete answer have no point of contact with biblical lament.”54

I am not so sure that they are right. In lament, regardless of response, “suffering is given the dignity of language.”55 Suffering can render us passive, voiceless, mute. As Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik (1903–1993) teaches, there is something inherently redemptive about finding words for our pain. “A mute life is identical with bondage,” he writes, “a speech-endowed life is a free life.”56 Even before they are saved by God—or even, for that matter, in situations when they are not saved at all—the psalmists accomplish something transformative simply by giving voice to their afflictions.

What I am describing here may in part be a psychological process, but it is primarily a relational one. It is not just that the psalmists speak; it is that they speak to someone—and not just to anyone, but to the One who created them, loves them, affirms their dignity, and hears their cries.57 In our own time many of us are more confident of God’s solidarity than we are of God’s salvation (though, looking around at the world each day, I cannot but have severe doubts about both). That may indeed represent a vast gap, or even a chasm, between us and our biblical forebears. Yet they have bequeathed us something precious and potentially transformational: the insistence that we need not lie about our suffering, the awareness that honesty is never a sacrilege, the courage to cry out, and the confidence that injustice is to be resisted rather than accepted.

Soloveitchik speaks of the redemptive power of petition—to give voice to our needs is to some degree to redeem ourselves. What I am suggesting, somewhat tentatively, is that a similar logic may apply to lament. In full-throatedly declaring that our suffering is too great to bear, and in unabashedly insisting that we do not deserve the anguish that we endure, we participate in our own redemption. Again, this has a psychological and existential dimension, but it has a powerful relational and theological dimension too. If suffering can make us feel passive and victimized, lament can restore our sense of dignity and agency. In mustering the audacity to speak to God in this way, the psalmist—and we who recite his words—declare, against all evidence to the contrary, that we matter, both to ourselves and to God.

It takes remarkable courage to remind God that when we die, we will no longer be able to sing God’s praises (vv. 11–13). In these words we implicitly declare that we matter to God; that when we die, God will lose praise—but not just any praise, our praise. As Kristen Swenson writes, “Of all the other people in the world, or even simply within the psalmist’s community, the psalmist assumes that God would lose out by allowing her, in all of her particularity, to die at this time.”58 If we die, we intimate, God will miss us.

Yet all of this notwithstanding, for many of us, to pray the laments is to make theological statements we do not mean. Responding to a recent query from me about what he makes of the psalms of lament, a prominent Christian theologian responded: “Lament gives us a true expression of the angst of the sufferer and a false view of God.” But can one embrace liturgically what she rejects theologically? I am honestly not sure.

Shai Held is president, dean, and chair in Jewish Thought at Hadar Institute.

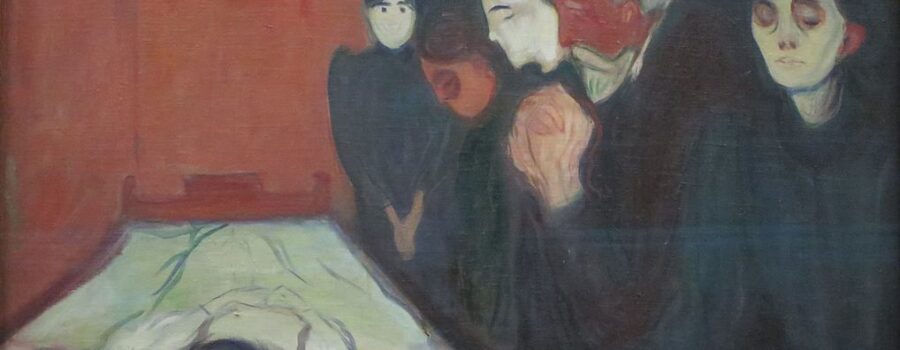

Image: Edvard Munch, At the Deathbed

- Held borrows this phrase from Kristin Swenson’s interpretation of Psalm 88, in Kristen M. Swenson, Living Through Pain: Psalms and the Search for Wholeness (Waco: Baylor, 2005), 141.[↩]

- David M. Howard Jr., “Psalm 88 and the Rhetoric of Lament,” in My Words Are Lovely: Studies in the Rhetoric of the Psalms, eds. Robert L. Foster and David M. Howard Jr. (London: T&T Clark, 2008), 132–146, at p. 132.[↩]

- Martin E. Marty, A Cry of Absence: Reflections for the Winter of the Heart (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 68.[↩]

- Artur Weiser, The Psalms: A Commentary (London: SCM, 1962), 586.[↩]

- For two notable exceptions see Carleen Mandolfo, “Psalm 88 and the Holocaust: Lament in Search of a Divine Response,” BibInt 15 (2007): 151–70; and Beth Tanner, “Psalm 88,” in The Book of Psalms, eds. Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth Laneel Tanner (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2014), 668–73. I came across Tanner’s commentary as I was completing my own study.[↩]

- Howard, “Psalm 88 and the Rhetoric of Lament,” 133.[↩]

- The rest of this paragraph summarizes (and closely follows) Robert C. Culley, “Psalm 88 Among the Complaints,” in Ascribe to the Lord: Biblical and Other Studies in Memory of Peter C. Craigie, eds. Lyle Eslinger and Glen Taylor (Sheffield: JSOT, 1988), 289–302, at pp. 292–93.[↩]

- Yet as we’ll see, one could suggest that the appeal to be heard in verse 3 is in fact a quotation of an earlier cry for help, mentioned in verse 2. It would thus not be a present-day appeal. So Erich Zenger, in Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51–100 (Minneapolis; Fortress, 2005), 394.[↩]

- The distinction between appealing to be heard and appealing to be helped may (biblically speaking, at least) be artificial; I am honestly not sure. In any case, as we’ll see, the psalm contains only one explicit petition and even this may in fact be a reference to a past petition rather than a present-day one.[↩]

- Hermann Gunkel, Einleitung in die Psalmen: Die Gattungen der religiösen Lyrik Israels (Götttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1985), 218.[↩]

- Toni Craven asserts that “One of the remarkable things about a lament is that despite the fact that God is frequently held responsible for the distress, the psalmists usually express unqualified trust in God’s good intention for them.” The author of Psalm 88 evinces no such trust and the psalm thus represents a dramatic exception to the rule. Toni Craven, The Book of Psalms (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992), 27.[↩]

- Richard J. Clifford, Psalms 1–72 (Nashville: Abingdon, 2002), 21.[↩]

- It may be present in verse 3 and is arguably implicit in the rhetorical questions of verses 11–13.[↩]

- Clifford, Psalms 1–72, 21. In this context note also Bernhard Anderson’s suggestion that “The laments are really expressions of praise, offered in a minor key in the confidence that YHWH is faithful and in anticipation of a new lease on life.” Bernhard W. Anderson with Steven Bishop, Out of the Depths: The Psalms Speak for us Today, 3rd ed. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2000), 60. Needless to say, Anderson’s claim has no purchase whatsoever on Psalm 88 (which, to his credit, he recognizes).[↩]

- Clifford, Psalms 1–72, 22.[↩]

- Claus Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms (Atlanta: John Knox, 1981), 72–73.[↩]

- A. Chadwick Thornhill, “A Theology of Psalm 88,” EvQ 87 (2015): 45–57, at p. 46.[↩]

- Westermann, Praise and Lament, 75.[↩]

- See, for example, Thornhill, “Theology of Psalm 88,” 46–47. And see also John Goldingay, Psalms, Volume 2: Psalms 42–89 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007), 644.[↩]

- Marvin Tate, “Psalm 88,” RevExp 87 (1990): 91–95, at p. 91. See also Leonard Maré, “Facing the Deepest Darkness of Despair and Abandonment: Psalm 88 and the Life of Faith,” OTE 27 (2014): 177–188, at p. 181.[↩]

- In (admittedly weak) defense of the emendation, one should note that the phrase אלהי ישועתי appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible, though ישועה does appear with other names for God. See, e.g., “El” in Isa 12:2 and Ps 68:20; and “Tzur” in Deut 32:15 and Ps 89:27. See Pyles, “The Depths of Darkness,” 16, n. 11.[↩]

- Thus yielding something like: “Lord, my God, by day I call for help, by night I cry out in Your presence.”[↩]

- Thornhill, “Theology of Psalm 88,” 51. Erich Zenger, among others, argues for maintaining the MT since “with its salvation perspective, [it] establishes the ‘positive’ contrast with the dominant negative statements, which is indispensable to the psalm.” Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 390.[↩]

- As I completed work on this essay, I was delighted to discover that Beth Tanner’s commentary had anticipated my own: “This is the first and last line of the psalm that is not one of anguish. Indeed, by the end of the psalm, this one line will scarcely be remembered for all the pain that pours out. In fact, by the end of the psalm, one may wonder if this epithet is an expression of great faith or great irony.” Nancy deClaissé-Walford, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth Laneel Tanner, The Book of Psalms (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2014), 671.[↩]

- For other negative uses of “sated,” see Job 9:18 and 10:15; and Lam 3:15.[↩]

- Davidson, Vitality of Worship, 290. This is cited virtually word for word, though without attribution, in Leonard Maré, “Facing the Deepest Darkness of Despair and Abandonment: Psalm 88 and the Life of Faith,” OTE 27:1 (2014): 177–188, at p. 183. Somewhat more soberly, Tate writes that חָפְשִׁי in the psalm means “set free,” that is, “relieved of the normal obligations of life, because family and community already judge the speaker to be dead and thus ‘free’ of the responsibilities of the living.” Tate, “Psalm 88,” 91. In the same vein, see also Anthony R. Pyles, “Drowning in the Depths of Darkness: A Consideration of Psalm 88 with a New Translation,” Canadian Theological Review 1 (2012): 13–28, at p. 17. Also worth noting in this context is John Goldingay’s astute comparison of “free” here to the expression “let go” used in business contexts to describe someone who wants to keep on working but is no longer wanted. Goldingay, Psalms, Volume 2, 649. Second Kgs 15:5, where בֵית הַחָפְשִׁית is used to refer to a place where lepers are quarantined, is likely also relevant here. Noting that the term חָפְשִׁי “usually denotes a free slave” (see Exod 21:5), Willem VanGemeren characterizes it as a “paradoxical expression, as though death brings freedom.” Willem A. VanGemeren, Psalms, Expositor’s Bible Commentary 5 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 659.[↩]

- The phrase הָיִיתִי כְּגֶבֶר אֵין־אֱיָל “I am a man without strength,” can also be taken ironically. The term גֶבֶר suggests strength and vigor; the psalmist is thus a man of strength and vigor devoid of . . . strength and vigor. On this, see Goldingay, Psalms, Volume 2, 648.[↩]

- Clinton McCann astutely observes that the psalmist’s use of three different words for crying out (צעק, קרא, שוע) serves to indicate that he “has exhausted every approach to God”—to no avail. J. Clinton McCann, “Psalms,” NIB 4 (Nashville: Abingdon, 1996), 1027.[↩]

- For this possibility, see Marvin E. Tate, Psalms 51–100, WBC 20 (Dallas: Word Books, 1990), 398; and Beth Tanner, in deClaissé-Walford, et al., The Book of Psalms, 671.[↩]

- Tate, Psalms 50–100, 403; see Ps 46:6; 90:14; 143:8; and Zeph 3:5.[↩]

- For an interpretation along these lines, see, for example, Richard J. Clifford, Psalms 73–150 (Nashville: Abingdon, 2003), 86. There appears to be some tension between the psalmist’s charge that God has actively assaulted and abused him, on the one hand, and his notion that God has turned God’s face away from him, on the other. In any case, the former image is dominant here. For another example of a lamenter who moves between accusing God of inexcusable passivity, on the one hand, and active cruelty, on the other, see Psalm 44 (compare vv. 11–15 with vv. 24–25).[↩]

- Although it seems extremely likely to me that Psalm 88 is about (chronic) illness, I do think it is possible to take the illness as metaphorical and to interpret the psalm as referring to some other form of (relentless, enduring) suffering. Note similarly Tate, who thinks the psalmist is ill but admits that “There appears to be no language in Psalm 88 which necessitates a direct reference to illness.” Tate, Psalms 51–100, 400. Tate is correct, unless we take מָחֲלַת in verse 1 to be a reference to illness (which Tate does not). See also McCann, “Psalms,” 1027, who notes that although the psalm seems at core to be about terminal illness, “the language is metaphorical and stereotypical enough to express other life-threatening situations,” as is evident from the fact that many traditional interpreters, both Jewish and Christian, understood the psalm to be giving voice to the suffering of an exiled people. See, for example, the commentaries of Rashi and Rabbi David Kimhi to the psalm.[↩]

- For a similar reading, see Beth Tanner, “Psalm 88,” in deClaissé-Walford, et al, The Book of Psalms, 671.[↩]

- Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 393.[↩]

- NIV and NRSV are similar. As Howard reminds us, הַטֵּה is the only imperative verb form in the entire psalm. Howard, “Psalm 88 and the Rhetoric of Lament,” 42, n. 26.[↩]

- See Erich Zenger in Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 394.[↩]

- Pyles declares that “The questions . . . are themselves a kind of plea” (Pyles, “Drowning in the Depths of Darkness” 19). Culley writes more colorfully that “Darkening the picture can be a form of persuasion.” Culley, “Psalm 88 Among the Complaints,” 291.[↩]

- Weiser, The Psalms, 586.[↩]

- Perhaps worth mentioning in this context is Carole Fontaine’s observation that “Those who suffer find their whole world bounded by experience of their pain. In a very real sense, every sufferer suffers alone and neither talk nor silence blurs that one reality.” Carole R. Fontaine, “‘Arrows of the Almighty’ (Job 6:4): Perspectives on Pain,” AthR 66 (1984): 243–48, at p. 244.[↩]

- Tate, “Psalm 88,” 93.[↩]

- Mandolfo, “Psalm 88 and the Holocaust,” 156.[↩]

- Kathleen Harmon, “Growing in Our Understanding of the Psalms, Part 2: Persisting in Prayer when God is Silent,” Liturgical Ministry 20 (2011): 52–54, at p. 53.[↩]

- Commenting on this psalm, Zenger writes that “When and where God can no longer be praised, his divinity is in question.” Zenger, in Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 396. This seems overstated to me. God’s divinity is not in question for the psalmist, but God’s goodness most certainly is.[↩]

- In the same vein Mandolfo writes: “There is no doubt that the supplicant in Psalm 88 contends and questions, but is there any evidence that she continues to trust or believe? And in what sense ‘believe’? There is no indication that the supplicant trusts that God will rectify the situation, but she prays nevertheless.” Mandolfo, “Psalm 88 and the Holocaust,” 164–65.[↩]

- Maré, “Facing the Deepest Darkness,” 187.[↩]

- More astutely, Zenger observes that the psalmist “evokes the image of the God who is proclaimed is Israel’s great traditions—which God now makes simply absurd for the petitioner.” Hossfeld and Zenger, Psalms 2, 395.[↩]

- Additionally, we must resist the temptation to soften the edges of the psalmist’s despair and thus to paper over the depth of his theological crisis. VanGemeren falls into this trap when he declares that “Though the psalm ends in a lament, faith triumphs, because in everything the psalmist has learned to look to the ‘God who saves.’” Such an interpretation flattens the text and refuses to confront its irresolution. VanGemeren, “Psalms,” 662.[↩]

- See, e.g., A.A. Anderson, The Book of Psalms (London: Oliphants, 1972), 623; and Karl-Johan Illman, “Psalm 88—A Lamentation without Answer,” SJOT 1 (1991): 112–20, at p. 120.[↩]

- Culley, “Psalm 88 Among the Complaints,” 291.[↩]

- It is worth contrasting the words of Mandolfo—”The supplicant of Psalm 88 is making an appeal, but is not for the removal of suffering, so far as I can see . . . she shows no sign of having any more hope of that happening[;] it is an appeal for explanation”—with those of Goldingay: “The one thing [‘why?’ questions] are not doing is asking for information, and if YHWH had an answer that could ‘solve’ the ‘problem of suffering,’ this would not mean that the suppliant could put away his or her pen and go home. The ‘Why?’ is more a challenge to action than an inquiry.” See Mandolfo, “Psalm 88 and the Holocaust,” 165; and Goldingay, Psalms, Vol. 2, 656. I’d be tempted to split the difference between these two approaches: the psalmist would obviously love for God to deliver him but by this point his hope has run thin (or perhaps run out), so barring salvation, he’d at least like an accounting of God’s appalling behavior. Of course, he may well be convinced that no coherent or defensible accounting is possible and so his question is actually more an accusation than a query.[↩]

- Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984), 81.[↩]

- Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms, 79.[↩]

- Mandolfo, “Psalm 88 and the Holocaust,” 166.[↩]

- Scott A. Ellington, Risking Truth: Reshaping the World through Prayers of Lament (Eugene: Pickwick, 2008), 29.[↩]

- Claus Westermann, “The Role of the Lament in the Theology of the Old Testament,” Interpretation 28 (1974): 20–38, at p. 31.[↩]

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah,” Tradition 17 (1978): 55–72, at p. 56.[↩]

- Coming at this from another angle, laments bind us to God even as we express disappointment with God; protesting God’s absence paradoxically makes God present.[↩]

- Swenson, Living Through Pain, 144.[↩]