Helen Paynter

“Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father.” (Matt 10:29)

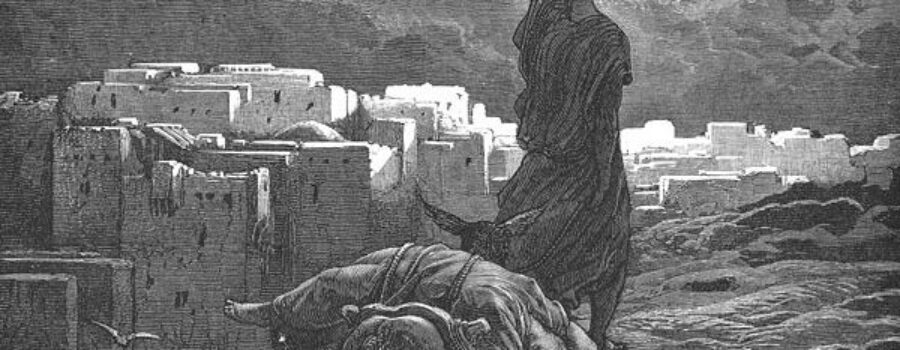

Judges 19 tells the gruesome story of an unnamed woman’s violent brutalization. But let’s begin by giving this woman a name.

Now, we shouldn’t read too much into her namelessness in the Scripture. Her husband isn’t named, either, nor her father, nor her abusers. But, because I’m going to speak about her a lot, because I want to dignify her memory, I’m going to give her a name. It’s the name I’ve called her for years. I’ll call her Beli-Fachad. It is Hebrew for “fearless one.”1

Very well.

But why is this story in my Bible? Why is this account of ancient mob violence in my sacred text? Quite frankly, why should I be obliged to read about rape, murder, and mutilation in this thing they call the “good book”? Don’t we get enough of this sort of thing on the evening news? In the past, I’ve had to send out a trauma warning before preaching this text, for crying out loud. Why should the Bible need a trauma warning?

What if Ghulam stumbled across this story? Ghulam grew up in Pakistan. And when I say “grew up,” I mean that at the age of eleven she was pulled out of school to marry a forty-year-old man. She’d hoped to become a doctor. Now she’s just concerned with whether she will survive the pregnancy she will conceive when she ovulates for the first time.

Or what if Salimata read it? Last summer, Salimata’s family sent her from the UK, where they live, on holiday to Senegal. One day, taken into the countryside on the promise of a picnic, she was bewildered and terrified to find herself in a group of screaming girls, pinned down and cut, so that she will never enjoy sex, and childbirth will endanger her life.

Ghulam and Salimata. Young women with no autonomy over their own person, no one listening to their opinion or seeking their consent. What might they think if they read about Beli-Fachad, whose own brief moment of autonomy is snuffed out, as her father hands her back over to the husband she has fled—her consent not sought in this male-only transaction?

Why is this story in Ghulam and Salimata’s Bibles? Perhaps because they would find themselves there. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it.

Or why is it in Olivia’s? Nine-year old Olivia Pratt-Korbel, was playing peacefully in her home in Liverpool when a man burst in through the front door.2 Earlier that day he’d fired two shots at someone he had a grudge against, and now he was running for his life. As he pushed open the door looking for somewhere to hide, he was shortly followed by his enemy, carrying a gun. Olivia had just enough time to scream, “Mum, I’m scared” before she was hit in the chest by a bullet intended for someone else.

Why on earth would Olivia’s Bible contain the story of Beli-Fachad? Perhaps because for those seeking to come to terms with her senseless death, they would find her in the story of another young woman who got caught up in something that had nothing to do with her, who stumbled into the violent rivalry of men, who ended up the victim of their brutality. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it.

What if this story were to fall into the hands of the family keeping vigil over little Mahmoud, who is in the Special Care Baby Unit of the Al-Quds hospital, Gaza—directly above the Hamas command centre which has its headquarters in the basement, trapped between the threat of imminent bombing by Israeli forces, and the knowledge that their baby’s tiny lungs will not survive being taken off the ventilator?

If Mahmoud’s family did open a Bible in Judges 19, they would find there the story of another human shield—a woman used to protect a man, as he literally stood behind her and then threw her out to endure the baying mob, a woman whose life was expendable because it was of less value than her master’s. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it.

Why is this story in our Bibles? How does it help?

It might help us when our social media feeds are full of the instrumentalization of violent deaths, like those of Omer and Omar. They were two four-year-olds killed in the early days of the Israel-Hamas war.

Little Omer was murdered in his own home when Hamas attacked the Kibbutz Nir Oz on 7 October. Little Omar was killed in retaliation just four days later in an airstrike on Gaza.

But since those murderous events, both their deaths have become the playground for propagandists. They have been both paraded and denied, with accusations of staged photos, dolls, and fake news.3 Claim and counter-claim. A story we find reflected in Beli-Fachad’s—as her own tragic death was exploited by her master for his own manipulative purposes, to whip up hatred and retaliatory violence. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it.

Why is this story in our Bibles?

I’ll tell you why this story is in our Bibles. Because it matters. Because the suffering and death of that low-status woman was significant in the story of God’s people. Because the atrocity she endured was not shrugged off as just one of those things. Because the narrator—and the Divine narrator who guided him—noticed. And cared. And memorialized. Because when the litany of ancient Israel’s abominations was being itemized, this story mattered enough for inclusion.

And that is why the story is in Ghulam and Salimata’s Bibles. That is why the family of Olivia might find hope in it. Because they find themselves here. Along with little Mahmoud, Omer, and Omar. Along with all the other expendable people that history forgets. Along with all the other people whose bodies are tools for others to use. Along with all the other children who get caught in the crossfire of battles that are not of their making. Along with all the women who find themselves in the hands of brutal men. Beli-Fachad’s story is theirs. Her trauma matters, and so does theirs. Her memory is held in the heart of God, and so are theirs. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it.

But I’m not done. Because I have to tell you that generations of—mostly male—interpreters have inflicted further violence upon Beli-Fachad and her memory.

So we must ask another question. Does the story matter? Does it really matter whether this story is told—and how?

The raped women and children of the Congo might think so. They might think it’s important that the story is told. When he received his Nobel peace prize for his work with the victims of extreme sexual violence, surgeon and Pentecostal pastor Denis Mukwege said this:

The Congolese people have been humiliated, abused, and massacred for more than two decades in plain sight of the international community. Everyone is using the natural resources of Congo, yet few are thinking it’s a stain on humanity to treat women and children the way they do. In the West they need our minerals for their phones, laptops and electric cars. But buying conflict materials is not acceptable and the world can’t say it didn’t have the possibility to stop it.4

Mukwege is speaking of victims whose stories aren’t considered very important. One might hope that the biblical commentators would share his compassion.

But sadly, Beli-Fachad’s story has been overlooked and over-written by many commentators through the years. They have described these final chapters of Judges as “an appendix on various themes” or have decentered her by declaring the story to be “all about hospitality” or “all about homosexuality.” A living commentator has minimized the crime against her by writing that the “heterosexual” rape is preferable to the threatened “homosexual” rape. One modern commentator wrote three pages of comment upon the story without using a single female pronoun.

What does that say to the rape victims of the Congo?

It matters that we tell Beli-Fachad’s story, and the story of those like her. Those of us who choose preaching topics and decide what matters are referred to in intercessory prayer must not replicate the mistake of these commentators. Rather, we should take our cue from Scripture itself, which memorializes nameless nobodies like Beli-Fachad.

And it matters how we tell her story.

Because, among those commentators who didn’t just write her out altogether, many of them found a different way to dishonor her memory. And that was by victim-blaming her. For centuries, Beli-Fachad’s brutal gang rape and murder has been described as her own fault. A direct consequence of her own actions in leaving her husband and being unfaithful to him. And when I say “through the centuries,” I mean right up to the present day. A commentary published just a few years ago said, “In the miserable end of this woman we see the hand of God punishing her for her uncleanness.”

There are at least two things wrong with this. First, the allegation against the woman is made on very slim textual grounds. And second, and far more importantly, God never—never—employs sexual violence against someone as punishment for their sins. For this purpose it doesn’t matter whether she had been unfaithful to her husband or not. He owed her his covenant loyalty, or at the very least he owed her protection out of common humanity.

Does it matter how we tell Beli-Fachad’s story?

Yes. It matters to the countless people—especially but not exclusively women—who have made disclosures of abuse or assault and then been told that it was their own fault. The victim of domestic abuse whose abuser tells her if only she didn’t infuriate him he wouldn’t hit her. Or who is told by her minister to go back home and pray to become a better wife. Or who is described by a social worker as a glutton for punishment because she doesn’t “just leave him.”5 Or the young girls abused by a pedophile ring in Rotherham, whose attempts to find safety were long delayed by police attitudes that they were just slutty white trash.6 Or the rape victim in Ireland whose underwear was held up in court by the defense barrister, who invited the jury to conclude that she had been expecting sex. Victim blaming. Victim blaming. Victim blaming.

It matters how we tell her story. And those of us who are called to interpret Scripture to the people of God must take this responsibility very seriously indeed.

But I want to conclude with one more story. And this is the most terrible of all.

I want to tell you about a man who—like Beli-Fachad—was born in Bethlehem in Judah. Like her on that fateful day, he had nowhere to lay his head. Like her, he was seized and held before a baying crowd before being given over to their bloodlust. Like her, he was lied about. Like her, he took the place of another who was under threat. Like her, he was stripped and beaten. Like hers, his body was broken. Like her, he died in dishonor and shame.

And in this way, he is Beli-Fachad. And he is Ghulam and Afisha. He is Salimata and Olivia; he is Mahmoud and Omer and Omar. He is all of these people, as he bears in his body not just the guilt of sin but its brutal weight.

Thanks be to God: Scripture remembers Beli-Fachad and all she endured. Because not a sparrow falls, but the Father sees it. And thanks be to God: the Savior participates in her suffering, in the suffering of the world.

It’s Friday. In the Ukraine and Russia, it is Friday. In Gaza and Israel, it is Friday. In the thousands of homes where abuse is going on, it is Friday. In the situations in this city, this country, and this world, where humans are still enslaved, it is Friday.

But thanks be to God: Sunday will come.

Helen Paynter is a UK Baptist minister and Tutor in Biblical Studies at Bristol Baptist College. She is the founding director of the Centre for the Study of Bible and Violence and the author of several books, including Telling Terror in Judges 19: Rape and Reparation for the Levite’s Wife, Blessed Are the Peacemakers: A Biblical Theology of Human Violence, The Bible Doesn’t Tell Me So: Why You Don’t Have to Submit to Domestic Abuse and Coercive Control and God of Violence Yesterday, God of Love Today? Wrestling Honestly with the Old Testament.

Image: Gustave Doré, The Levite Carries the Woman’s Body Away (Jud. 19:28–30)

- I explain why I’ve chosen that name for her in my book Telling Terror in Judges 19: Rape and Reparation for the Levite’s Wife (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020):

On 16 December 2012, a 23 year-old woman, Jyoti Singh, got onto a bus in Delhi along with a male friend, Awindra Pandey. It was 9:30 p.m. and they had been watching a film together. On their way home they had been set down by a rickshaw driver in a dangerous area and were relieved to find a bus apparently going to their destination. It was a private bus, and there were only six other people on it (all of them men), including the driver. It is unclear exactly what happened next. It may have been that the men intended to rob the couple. It may be that they were looking for a woman to rape. What is clear is that an hour and a half later, Jyoti and Awindra were thrown off the moving bus, semi-naked. Awindra had some limb fractures and bruises. Jyoti had been beaten, bitten all over her body, and raped many times, including with a hooked iron bar. Her bowel injuries were unsurvivable and she died in hospital around a fortnight later, but not before she had made a dying declaration which was used in the trial of the men eventually convicted of the atrocity. In fact, one of her three statements was made through the use of gesture rather than speech, but was nonetheless described by the judge as “true, voluntary and consistent.” Jyoti’s death sparked international outrage and mass, violent protest in Delhi and beyond. It will be clear that this story has many points of similarity with that of Beli-Fachad. Both women were assaulted in a place that should have been safe but turned out to be murderous. For Beli-Fachad, it was the Israelite city of Gibeah (vv. 11–13); for Jyoti it was a bus. (Jyoti and her friend had been set down by the rickshaw driver in an unfamiliar part of town; they probably gave a sigh of relief when they were able to board a bus to their destination.) Both women were travelling with a man who might have been expected to protect them, and who managed to survive the night’s events, when the women didn’t. Both women were raped and abused by night, then discarded (v. 25). Both women’s murders evoked widespread outrage and violent reaction (chapters 20–21). Both women have been blamed for the assault that killed them. Indian law prohibits the naming of victims of sexual violence. Until Jyoti’s anonymity was waived by her family, the Indian press dubbed her Nirbhaya, meaning fearless; a tribute, I think, to the courageous way in which she resisted her attackers, fought for life for a fortnight afterwards, and made a dying declaration which testified powerfully after her death. For these reasons, because of her enduring voice and her silent but powerful testimony, I chose the Hebrew translation of ‘Nirbhaya’ as the name for the woman of the biblical story: Beli-Fachad, Without-Fear.[↩]

- Robyn Vinter, “Olivia Pratt-Korbel Said ‘Mum, I’m Scared’ Before Killer Shot Her, Court Told,” The Guardian, March 7, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/mar/07/olivia-pratt-korbel-scared-killer-shot-her-court.[↩]

- Marianna Spring, “Omer and Omar: How Two 4-Year-Olds Were Killed and Social Media Denied It,” BBC, October 25, 2023, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-67206277.[↩]

- See Christina Lamb, Our Bodies, Their Battlefields: War Through the Lives of Women (New York: Scribner, 2020), 316.[↩]

- See Natalie Collins, Out of Control: Couples, Conflict and the Capacity for Change (London: SPCK, 2019), 102.[↩]

- See Helena Kennedy, Misjustice: How British Law Is Failing Women, (London: Vintage, 2018), 296.[↩]