Sarah Lawson

What does it mean to have a large word-hoard? Can I trust a leechcrafter? And how scared should I be of hell-hawks? In short, how do I know what rare words mean? These three words are hapax legomena (words which only occur once) in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings,1 and scholars like me aim to find a method for answering these and similar questions for the rare words of the Bible.

Hapax legomena refers to “words which only occur once in a given corpus.” The corpus may be a single work, a collection of works, an author’s entire body of work, or an entire language. For my research, the corpus is the New Testament in its original Koine Greek.

Now, some treat such singular words as “golden specks in the whole work”2 which bear special significance or can unlock entire worlds of meaning within a text. However, it is a simple matter of mathematical probability that up to 50% of the vocabulary of any given text would be unique.3

All of this is to say that hapax legomena aren’t special. They’re just rare . . . and extremely common.

But why are rare words so common?

Commonly Rare Words

Statistical linguist George Zipf popularised4 what eventually became known as Zipf’s Law, which states that in a given corpus of language use5 there is a distribution of words broadly following a formula where “the rth most frequent word has a frequency f(r) that scales according to f(r) ∝ 1/r^α for a≈1.“6

In non-math speak, this means that the second most frequent word will appear roughly half as often as the most frequent, the third most frequent will appear a third as often as the most frequent, and so on.

The most frequent word in the Greek New Testament is ὁ (“the”) at 19,865 instances. According to Zipf’s Law, we should expect the 10th most frequent lexeme εἰς (“into”) to appear 1/10th as often, roughly 1,986 times (it appears 1,767), the 20th ἐκ (“from”) to appear 1/20th as often, roughly 993 times (it appears 913), the 30th ἔρχομαι (“to go”) to appear 1/30th as often, 662 times (632), and so on.7

This is not a perfect law, and there have been attempts to refine it,8 but the pattern is clearly there.9 Depending on how you count and which texts you use, there are approximately 3,414 words which appear only once in the Bible, which account for nearly 25% of the total vocabulary. In the New Testament alone there are approximately 1,934 hapaxes of 5,436 lexemes,10 or 36% of the total vocabulary.

So, there are a lot of “rare” words. So what?

Overlooking Hapaxes

Unfortunately, these words tend to be largely neglected.11 Plenty of the Bible’s original words have been studied to within an inch of their lives, but these tend to be the more common or theologically dense words.

The rest have somewhat languished on the sidelines as lexicographer after lexicographer has simply assumed they know what the word means because they know (or think they know) what the verse means or because they trust the guy who came before and haven’t wished to spend their limited time and resources investigating a word which only affects one line in the entire Bible.12 Add to this the general animosity toward word-studies in biblical studies in general since James Barr’s paradigm-shifting work in 1961, and we find that little new linguistic study has been done on words outside of the core theological vocabulary in decades.

However, it is my contention that studying these rare words is of vital importance if we want to truly understand the text at hand. Some could fundamentally change how we understand the teachings of the Bible, but most won’t. A great many of these words may indeed have very little impact on our understanding of the Bible at all. But thousands of very little impacts add up to a potentially very large impact, and our current understanding could suffer a death of a thousand cuts.

To put it another way, imagine that our current understanding of the Bible, due to the under-study of these rare words, is like Swiss cheese, full of little holes. It’s still cheese, it’s still delicious, but not as “full” as it might otherwise be if we could fill in the holes.

So how do we fill in the holes?

Reading the Rare Words

Generally, when linguists examine the meaning of words—that is, their semantic potential—they like to get native speakers involved. But, alas, as a “dead” language, Koine Greek has no native speakers anymore, despite sharing a number of characteristics with the Katharevousa and Demotic (Standard Modern Greek) dialects of Modern Greek. So, for my research I have to plumb the depths of contemporary linguistic methodology and devise a few strategies of my own to get the job done.

My proposed method is eclectic, taking a number of different approaches from different schools of linguistic thought. While most pastors and lay Bible readers won’t engage in this kind of study, they can certainly benefit from its fruits, and it may prove intriguing and helpful to get an inside look at the type of legwork involved in unravelling the riddle of rare words. What follows is a flyover summary of sorts:

1. Examine the phonology of a word, how the sounds work together and change over time. This rarely affects meaning but is important groundwork.

2. Look at the morphology of the word, how the meaningful “bits” of the word come together contribute to the word, like Lego building bricks.

3. Analyse the semantics of the word. This step may include componential analysis, prototypicality, frame/domain delimitation, conceptual metaphor involvement, and semantic change processes over time.

4. Look at the etymology of the word, both scientific and folk, to see where the word came from in history and the minds of the people who used it. Care must be taken here to not read meanings into the word of which the users were not aware.

5. Examine the cotext, or written context, of the word. Of special interest here are what words overlap or contrast meaning with it (paradigmatic relationships), how it relates to the words around it in the text (syntagmatic relationships), and the words or ideas it appears with throughout the ancient Greek extant literature (collocations). This often involves reading dozens if not hundreds of lines of ancient Greek, and as such tends to be the most time-consuming part of the process. Discourse analysis can also aid in thinking about how the genre of the text, speech-act theory, coherence, and prominence might affect what the word means.

6. Look at the context, or world outside the text, of the word. What was the relationship like between the writer and their audience? Did the writer refer to any other texts as they wrote? Does this word have any special connotations? And how have people understood this word throughout history? Just because we’re doing a word-study doesn’t mean we forget good hermeneutics!

7. Consider the text critical data such as the ancient translations of the Bible into Latin, Syriac, Coptic, and Armenian, as this can create a kind of Venn-diagram of possible senses of the words. Also of interest is how the early Greek Church Fathers understood it as native speakers, and whether any copyists along the way understood it differently.

8. Finally, I summarise all that information into a (hopefully) coherent argument as to what the word means in a far more detailed manner than any current dictionary can.

“God, Who Gives . . . Generously?”

Let’s look at an example step by step. ἁπλῶς, an adverb found in James 1:5, is translated by almost every English edition of the Bible as “generously.” However, my method shows that this is not accurate and misses some of the artistry James includes in his writing.

1. Looking at the phonology, ἁπλῶς was likely originally pronounced approximately /hæp ‘los/, and no other phonological issues exist for this word.

2. Examining morphology, the word is comprised of two morphemes: an adverbial suffix of manner and the base morpheme whose root word ἁπλοῦς (uncontracted ἁπλόος) referred to a singleness of purpose, sincere, open, or straightforward. This core meaning sometimes extended to generosity. When compared with other derivatives of this root ἁπλότης, ἁπλοτομέω, ἅπολωμα, ἁπλωτικός and verb form ἁπλόω, there is a recurring concept of singularity and simplicity.

3. Semantically, the core components of ἁπλῶς are [+simplicity] and [+manner of action], with an occasionally cancellable [+singularity] feature also present. As I delimited the domains in the ἁπλῶς frame I found a quite wide range of senses, outlined below:

| ἁπλῶς Frame | |

| Domain | Explanation |

| Moral and Ethical Qualities and Related Behaviour | A manner of behaviour which is morally simple or pure |

| Honesty/Sincerity | A manner of behaviour which is sincere or open; upright |

| Moral Simplicity | A manner of simple action manifested in generosity |

| Logical Simplicity | A manner of simple action manifested in unconditionality |

| Pejorative Simplicity | A manner of action which is naïve, foolish, without refinement, artless, or superficial |

| Wholeness Simplicity | Totality, essentiality, or absoluteness of action |

| Purpose | Singleness of purpose of action |

| Mind | Singleness of mind |

| Communication | A simple or straightforward manner of verbal expression |

| Measurements and Numerals | Singularly, in one way |

| Giving | A manner of giving by the initiative of the giver without incurring obligation from the receiver |

| Common Behaviour | A manner of action which is moderate or ordinary |

In terms of semantic change over time, it appears the sense of “singularity” was the initial sense, used as early as the 7th century BCE by Plato and Xenophon (Thuc. 3.18.4). The lexeme then underwent a change through metaphorical use which resulted in expansion toward the sense of “simplicity,” then to “openness” and “sincerity,” and possibly on toward “generosity.” It appears the same process further expanded the semantic range to the specific sense of “simplicity in verbal expression.” The reason for this semantic change appears to be a conceptual metaphor involved with ἁπλῶς wherein moral purity is singleness / moral impurity is multiplicity. This could explain why the initial senses of “singularity” and “simplicity” expanded toward more moral concepts of honest, openness, sincerity, and generosity.

4. Examining the etymology reveals that ἁπλόος, contracted to ἁπλοῦς then derived to ἁπλῶς, is the direct opposite of διπλόος (διπλοῦς/διπλός) meaning “double.” No data earlier than this still exists. Some propose a root of *pel- “to fold” connecting it to Latin “Simplus, duplus…,” “simple, double,” and Germanic/Gothic “tweifl” “doubt” though this is uncertain at best. The connection to διπλόος suggests a “single” or “simple” sense.

5. Considering cotext, I’ve found the ἁπλῶς lexeme is in contrastive and inclusive relationships with many lexemes referring to “giving” type actions. It also has an overlapping relationship with ἁγνῶς (purely motivated, sincere), ἁπλοῦς (simple, sincere), ἁπλόω (to make single), ἄδολος (guileless, sincere) and εἰλικρινής (unalloyed, pure). It is in an opposite complementation relationship with φειδομένως (sparingly). It is also in an opposite complementation/infinite series relationship with διπλοῦς (twofold, double) and δίδυμος (double), τρίδυμος (triple), τετράδυμος (quadruple), and onward.

In terms of necessity, while it indeed has a possible relationship with “generosity,” it has an expected relationship with “singular” and “moral purity.”

This lexeme could be part of an antithesis construction where τοῦ διδόντος θεοῦ πᾶσιν ἁπλῶς (God who gives to all [in ἁπλῶς manner]) is contrasted with μὴ ὀνειδίζοντος (not reproaching/insulting). Suggesting a possibility of a meaning opposite to “reproachfully/insultingly.”

This word is reasonably common outside of the Bible, so there is much collocation data with which to work. In over 1500 instances, it only modifies a form of δίδωμι “to give” 9 times. I suggest that if “generously” were the most salient sense of this lexeme, we would expect to see it collocated with δίδωμι more frequently. Compare this to 57 occurrences of it modifying a form of λέγω in line with the communication sense of simplicity of speech, which most lexicons currently list as less prominent, if at all.

Moving to discourse analysis, the script activated by δίδωμι may initially seem to favour a sense of “generosity” for ἁπλῶς. However, that these words are so rarely collocated suggests ἁπλῶς may not actually be part of the expected script for δίδωμι. This lexeme may be introducing a schema which returns a number of times in James to do with single- versus double-mindedness, either positioning God as inherently singular in motive/mind or the person to whom God gives as characterised by singularity of motive/mind. The latter would position the one who receives as the counterpoint to the δίψυχος “double-minded” and create a stronger tie between Jas 1:5 and the following sentences, though the former is more likely syntactically.

6. Looking at context, though James does not appear to draw on any particular text in this line, the intertextual relationship between James and the Shepherd of Hermas could prove illuminating. The Shepherd of Hermas, which has been argued to be highly dependent on James, is particularly fond of using ἁπλῶς in the sense of “simple goodness” and “without hidden agenda.” This could indicate that Hermas—and those in his social semantic group, which was very similar to the original audience of James—may have understood this word primarily in these terms, rather than “generosity.”

Connotatively, ἁπλῶς has a [+ethical goodness] value which is quite strong relative to the denotative senses. This connotation likely contributed to more and more positive senses gaining inclusion in this lexeme over time, similarly to the English word “pure” moving from “unmixed/homogenous” toward “clean” then “free from moral corruption.”

7. Turning to the text-critical data, such as the early translations, the Latin Vulgate uses “affluenter” which has the senses of “abundantly” and “luxuriously.” The Syriac Peshitta uses ܦ݁ܫܺܝܛܳܐܝܺܬ݂ which has the senses of “simply,” “generally,” “foolishly,” “stand erect,” “buy without warranty,” and “freely/liberally.” The Sahidic Coptic uses ϩⲁⲡⲗⲱⲥ, which has the senses of “simply,” “rather/instead,” “openly,” and “in short/basically.” And the Armenian uses առատապէս, which has the senses of “abundantly,” profusely,” and “fruitfully.”

The Latin and Armenian overlap in the sense of “abundantly,” which when attached to a verb of giving agrees with traditional interpretation. The Syriac only overlaps with these in the sense of “liberally,” which appears to be an obscure sense of this word, only listed in one lexicon.13 The most salient sense of the Syriac, “simply,” overlaps with the most salient of the Coptic, which agrees with what I have argued is the most salient sense of the Greek. This data tends toward the traditional “generously” interpretation; however, it is clear that some early interpreters also understood ἁπλῶς differently, preferring a “simply” type reading. There are no textual variants or mentions of this verse in the Greek Church Fathers.

8. In summary, I’ve found that the most salient sense of ἁπλῶς is centred on “singularity” or “simplicity” from which, via a conceptual metaphor, a number of other domains emerged over time. This is supported by the morphology and etymology. The cotext was particularly illuminating for this lexeme, as I found very few instances supporting a traditional interpretation, and the cotext of James in particular with the theme of “single- vs double-mindedness” strongly supports a “singular” interpretation. The use of this word in a similar sociocultural context which is argued to be highly dependent on James, the Shepherd of Hermas, is also a strong piece of evidence supporting a “simplicity” type sense. Among evidence supporting the traditional interpretation, the early translations were the strongest, however the Coptic stands as an indication that “generously” was not the only early interpretation.

So what’s the “payoff,” so to speak? In light of all the above, I argue that James uses ἁπλῶς to introduce his theme of single/double by characterising God as a single-minded giver, simply motivated, or without strings attached. Thus, the traditional English translation “generously,” while not completely off the mark, is misleading and obscures some of the careful skill James put into his work.

Filling in the Holes

This attentive and eclectic approach affords a pathway for scholars to fill in a few of the lexicographic holes in New Testament research. While I do not expect any given individual word to drastically change how we understand a passage, I suspect a thousand tiny changes in nuance across that 25% of the biblical vocabulary may have a significant impact on our understanding of and appreciation for one of the most influential texts in history.

Sarah Lawson is a PhD student at Charles Sturt University, a council member and preacher at Mount Barker Baptist Church, and a teacher of Certificate III Christian Ministry and Theology at King’s Baptist College. You can find a few more hapax tidbits here.

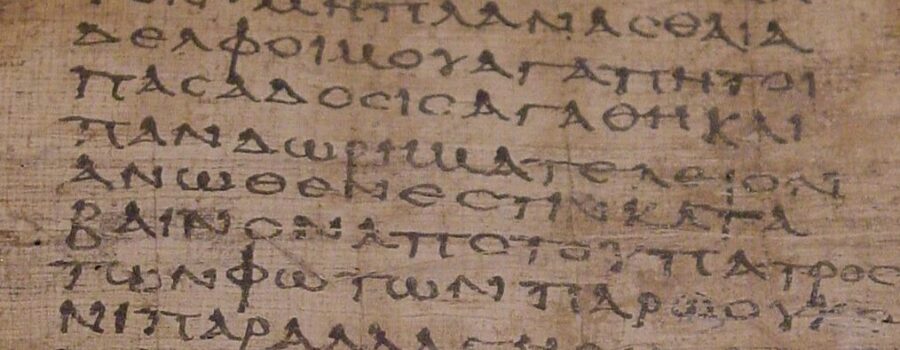

Image: Papyrus 23 (c. AD 250)

- Jason Fisher, “Some Contributions to Middle-Earth Lexicography: Hapax Legomena in The Lord of the Rings,” in The Years Work in Medievalism, ed. Edward Risden (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2012), 36–48.[↩]

- Robert Burchfield, Unlocking the English Language (New York: Hill and Wang, 1991), 12.[↩]

- F. Fan, “Squibs: An Asymptotic Model for the English Hapax/Vocabulary Ratio,” Computational Linguistics 36.4 (2010): 631–37; H. Baayen, “The Effects of Lexical Specialization on the Growth Curve of the Vocabulary,” Computational Linguistics 22.4 (1996): 455–80; A. Kornai, “How many words are there?” Glottometrics 4 (2002): 61–86.[↩]

- He was not necessarily the first to notice it—Jean-Baptise Estoup (1916) and Felix Auerbach (1913) both noted the correlation. C. D. Manning and H. Schütze, Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), 24; F. Auerbach, “Das Gesetz der Bevölkerungskonzentration,” Petermann’s Geographische Mitteilungen 59 (1913): 74–76.[↩]

- This law applies to every language—contemporary, ancient, extinct, as-yet-untranslated, and even fictional—and every corpus of significant size (more than a few sentences), human-created or computer-generated.[↩]

- G. Zipf, The Psychobiology of Language: An Introduction to Dynamic Philology (London: Routledge, 1936); G. Zipf, Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1949); S. T. Piantadosi, “Zipf’s Word Frequency Law in Natural Language: A Critical Review and Future Directions,” Psychon Bull Rev. 21.5 (2014): 1112–30.[↩]

- C. J. Fresch, A Book-by-Book Guide to New Testament Greek Vocabulary (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2019), 1, 13–14.These frequency rates were confirmed by Fresch in a personal communication (as his book only provides the highest and lowest frequencies for each ten-word list but lists the lexemes in alphabetical order).[↩]

- Notably by Benoit Mandelbrot with: f(r) ∝ 1/(r+β)^α.[↩]

- The resulting values for our examples are: εἰς (1,564), ἐκ (875), and ἔρχομαι (607). Still not perfect, but closer. B. Mandelbrot, “An Informational Theory of the Statistical Structure of Language,” in Communication Theory, ed. Willis Jackson (London: Butterworth, 1953), 486–502; “On the Theory of Word Frequencies and on Related Markovian Models of Discourse,” in Structure of Language and its Mathematical Aspects, ed. Roman Jakobson (Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, 1961), 190–219; Piantadosi, “Zipf’s Word Frequency Law in Natural Language,” 1112–30.[↩]

- R. Morgenthaler, Statistik des neutestamentlichen Wortschatzes (3; Zurich: Gotthelf, 1982), 38, 67–157, 168, 173.[↩]

- Helen Mardaga, “Hapax Legomena: A Neglected Field in Biblical Studies,” Currents in Biblical Research 10.2 (2012), 264–74.[↩]

- J. A. L. Lee, “The Present State of Lexicography of Ancient Greek,” in Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker, ed. B.A. Taylor et. al. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 66–74.[↩]

- It is possible this occurrence is as a result of the traditional interpretations of Jas 1:5.[↩]