Andrew R. Stroud

For pastors and spiritual leaders, the stress, isolation, and myriad tensions—whether social, political, or theological—of the past several years have undoubtedly left many feeling discouraged, apathetic, and at a loss as to why they are even in ministry and how they are ever supposed to keep going.

In their short guide to pastoral ministry Pastoral Leadership: For the Care of Souls,1 Harold Senkbeil and Lucas Woodford endeavor to provide timely encouragement for those wearied by pastoral ministry and to reorient their focus to the primary—and essential—duty of that calling: the care of souls rescued and redeemed by the blood of Jesus Christ.

As they write, “The heart of all leadership and strategic planning is the care of souls” (126). The care of souls is “love in action—the enactment of the word of God…the way pastors demonstrate their love for the Savior, who first loved them” (127). Anecdotally drawing on their combined decades of pastoral experience and their own commitment to the faithful practice of love-in-action that is the care of souls, Senkbeil and Woodford provide a brief but incredibly helpful reminder of the weighty worth of pastoral ministry. They not only describe a “better way” to orient the tasks of pastoral ministry around the central importance of soul-care but also demonstrate soul-care and pastoral encouragement toward the reader.

***

Senkbeil and Woodford begin with a sobering reminder. They write, “Sheep just milling around on their own are a disaster in the making. They need protection. They need guidance. They need leadership. They need feeding. In short, they need shepherding” (xvi).

As the rest of the book demonstrates, these words are not written in a spirit of condescension or exasperation toward the flock of God. Rather, they remind the pastoral leader that those placed sovereignly under his care are valuable, worthy souls and that God has stewarded essential parts of their spiritual protection and formation to him as he labors in the grace and power of Jesus.

The care of souls is essential, the very heartbeat of pastoral ministry. To illustrate how quickly and easily, especially in our current cultural context, the priority of soul-care can be pushed aside or neglected altogether, Pastoral Leadership begins with a cautionary tale.

In chapter one, Lucas Woodford describes his early experiences of pastoral ministry—years of leading a church and a Christian school, of leading a congregation through a tumultuous building project—all tasks which led Woodford to believe that “if I worked more, tried harder, and was a better leader,” all would be well (5). Finally, he came to realize that leadership skills and principles alone were not enough for effective pastoral ministry. Nor were they at all enough for the care of souls. He relates that “it was also at this point that I began to see the care of souls…was far more than my ability to be a good leader” (10). The antidote to his burnout and discouragement, alongside getting help from his fellow leaders and the congregation itself, was to focus more intentionally on the care of souls by simply “giving them Jesus…rather than giving them myself” (11).

In chapter two, Woodford counters his cautionary tale with a necessary reminder that, while pastoral ministry does not only require leadership skills, it does require intentional and diligent focus on leading the sheep of Christ as part of effectively caring for their souls. Leader-less sheep are not cared-for sheep. This is an immensely practical chapter in which Woodford advises pastors to know their congregations, to know their expectations, to know the team of leaders around you, and to know what direction you hope to lead the sheep. Woodford encourages the reader to develop some sense of an awareness of “team dynamics,” communication skills, and other basic leadership skills that will help reduce leadership fatigue, risk of burnout, and vision-less care for the souls of the congregation.

Harold Senkbeil takes over in chapter three and writes about the soul-care of leading the sheep themselves. He wisely notes, “You’ve got nothing to give them you have not first received” (53). In this chapter, Senkbeil describes a simple but profound distinction between authority—in this case, the authority stewarded to pastors by Christ himself—and power, the raw wrenching of souls to and fro on the whims and personal preferences of the pastor (54). With this distinction between Christ-authorized authority and personal power in view, Senkbeil provides helpful guides and steps to achieve effective administrative and strategic goals in the practical leading of a congregation, all while maintaining a primary focus on the care of their souls in Jesus’ name.

Chapter four represents the practical demonstration of soul-care, even toward unknown readers. Senkbeil first identifies the issue of primary concern: pastoral burnout and the abandonment of ministry caused by loss of “pastoral identity” (93). Though Senkbeil provides little definition of what precisely he means by “pastoral identity,” this seems to refer to the pastor’s sense of personal calling and anchoring conviction as to what his pastoring is ultimately for. Its loss leads to pastors operating woodenly, as if they were merely figures in a play—filling a role, reciting lines until, finally, it’s just not enough anymore.

The disillusioned pastor feels spiritual numbness, as if “he’d developed callouses on his soul” (99). Ultimately, however, Senkbeil contends that “the real culprit is pride. We’re so damned arrogant that we think it’s all about us” (105). To remedy this problem, Senkbeil begins with the grace and forgiveness found in Jesus (111), even as he describes solutions such as counseling, medical intervention, and other tools of common grace that might save a man not only from losing his ministry but from losing his very life and soul (120).

Chapter five, written by both Senkbeil and Woodford, is a fitting conclusion. It is well described in a single word: balance. By willingly submitting to the intentions of God for his church to be led and shepherded by multiple leaders, gifted and filled individually by the Spirit, the church—made as it is of individual souls—is properly and healthily cared for. Yet so too are the leaders themselves cared for as their gifts and abilities are balanced and enhanced by those to whom they are accountable and to whose leadership and shepherding they submit. The balance which Senkbeil and Woodford describe leads not to a utopia of pastoral success where “never is heard a discouraging word” but to a place saturated with Jesus-dependency, where failures are met with grace, where soul-sickness is met with redemptive health, and where Christ’s sufficiency triumphs as his grace “is made perfect in weakness.”

***

There are few weaknesses in Pastoral Leadership: For the Care of Souls. It is a balanced and helpful book, sure to be an encouragement in some way to any pastoral leader who reads it. Minor points of difference might arise for those unfamiliar or uncomfortable with certain aspects of the authors’ Lutheran ecclesiology that are very briefly alluded to in places.

The section which raised the most questions in the mind of this reader was Harold Senkbeil’s description of pastoral burnout in chapter four. Senkbeil argues that pastoral burnout is primarily due to a crisis of what he terms “pastoral identity” (93). He writes, “I believe the largest factor in the startling number of pastors who resign their calls or are driven from them by dysfunctional congregations is the loss of pastoral identity” (93, emphasis added). He describes, with the insight of years of observing the process happen, the all-too-common way in which pastoral ministry dissolves as a man slowly loses his pastoral identity.

While perhaps outside the scope of this small book, this could have been a helpful moment to pause and consider the meaning—at least as Senkbeil understands it—of pastoral call. There is to Senkbeil a clear connection between call and pastoral identity. To lose the latter is to lose the former, or at least be in grave danger of doing so.

To his great credit, Senkbeil does not speak disparagingly of those whose depletion leads to departure from vocational ministry. In fact, he encourages them to find help and healing (117). Neither does Senkbeil imply that success in ministry is directly related to faithfulness. That is, faithfully doing the bidding of Jesus is not alone a guarantee for fruitful or prolonged ministry. Yet what we might call “failure”—pastoral burnout and the subsequent departure from office—is seemingly described by Senkbeil as the end of a negative chain of actions and reactions by a pastor, some intentional and some not.

But is there a place for “failure” in the lives and ministries of those who are, by most measures, faithful? Certainly, we would not excuse pastoral care that is willfully sinful or self-reliant. Yet could it be that, in some circumstances, pastors might be doing exactly what Jesus asks of his shepherds, in full submission to the call of God on their lives, and fail spectacularly by human standards, even to the point of removing themselves from vocational ministry to serve the Lord and witness to his kingdom in other endeavors?

Should we understand pastoral calling necessarily as a lifelong phenomenon, or might we better conceive of it as a particular service to a particular community for a particular time? Is vocational change synonymous with abdication? Or might it be, in some cases at least, the healthiest and humblest course of action available, one which may require and evidence a profound faith in the sufficiency and provision of Christ?

***

Overall, Pastoral Leadership is an excellent and helpful resource. Its readability, simplicity, and gentle tone make it a joy to read. Its content is general enough to be related to most circumstances, yet specific enough to provide applicable and relevant advice to particular difficulties of pastoral ministry.

Perhaps most helpful is the authors’ ability to describe how biblically qualified leadership functions in most church settings. It is perhaps most common in books about pastoral leadership to focus on the biblical qualifications relating to a man’s ability to teach, his moral character, or his marital and familial life. Yet it is also necessary to remember that elders are called to “manage the household of God.”

Senkbeil and Woodford are commendably careful in guiding their readers away from a vision of pastoral leadership more reflective of corporate management than Christ-like soul-care. Their heart of concern for the character of a pastor is always evident, implicitly and explicitly. Yet both Senkbeil and Woodford weave the explicit biblical expectations for pastoral character and care into the contextual specifics of a twenty-first century American church.

We need not be alarmed when Senkbeil and Woodford describe the importance of understanding “the basic dynamics of team ministry, personalities, how to regularly communicate, and what it takes to make it through the difficult and yet very rewarding reality of team ministry” (29). By encouraging pastors to lead well by, for example, communicating clearly (33) or maintaining a vibrant staff culture (35), they describe various—and sometimes neglected—ways in which a pastor can humbly and effectively live out the full array of biblical qualifications for the office.

Above all, the greatest quality of Pastoral Leadership: For the Care of Souls is its unflinching focus on the Savior and Shepherd of the Church, Jesus Christ, whose grace and peace are the greatest sources of soul-care to shepherds and sheep alike. Any and all pastors, especially in these seasons of difficulty and discouragement, would be well-served to carefully read and return again to Pastoral Leadership for the enrichment of their ministries, the encouragement of their hearts, and the care of their souls.

Andrew R. Stroud (MDiv, Virginia Beach Theological Seminary) lives in Norfolk, Virginia with his wife and two-year old daughter where they are active members of Trinity Presbyterian Church (PCA).

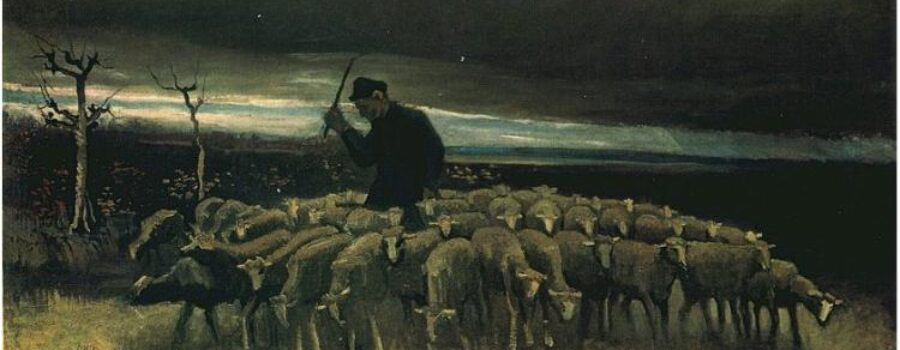

Image: Vincent van Gogh, Shepherd with a Flock of Sheep

- Harold L. Senkbeil and Lucas V. Woodford, Pastoral Leadership: For the Care of Souls, Lexham Ministry Guides (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2021).[↩]