Sandra L. Richter

I gave my first public message on the issue of environmental stewardship in 2005 at Asbury Theological Seminary’s Kingdom Conference. Historically, the goal of this conference has been to engage students in larger conversations regarding Christian responsibility across the globe. Standard topics have included training for effective cross-cultural communication; messages from courageous Christian cross-cultural workers (aka “missionaries”); organizations such as Word Made Flesh and SEND International; and ministries committed to assisting orphans, refugees, and trafficked women. Never had Asbury’s Kingdom Conference taken on environmentalism.

But in 2005, under the courageous leadership of ethics professor Christine Pohl, the committee took the plunge. It was a tense moment for everyone. In central Kentucky in 2005, this was not a topic that “the church” talked about. At least not from the pulpit. But being young and idealistic, I said yes to the event and dove in with a full heart. I was determined to reach my audience in a fashion that would engage and challenge without offending. And in the twenty-five minutes allotted to me, I preached my heart out. To my joy, my community responded with the same—wide-open hearts. The end result? This moment launched a movement at Asbury that is still moving forward.

We definitely had our challenges. There was more than one accusation of “hippie do-gooder-ism.” There were lots of questions about finances and labor, and there was one particularly telling faculty meeting in which I had to actually show my colleagues where to find the numbers on the bottom of their plastic water bottles and explain what the numbers meant! But we moved forward, and we created one of the most effective institutional recycling programs I’ve ever seen.

But as with so many efforts toward individual and systemic reform, the Asbury community was only able to respond to this challenge because the issue was addressed via the community’s own value system. In this case, Asbury needed to hear a biblical argument as to why environmental stewardship matters to the kingdom.

So how does one mount a biblical argument on this topic? Like all issues of faith and praxis, to determine whether a value is biblical, it must be subjected to a survey of the biblical text. As interpreters and exegetes, we must ask the question: Do I see this particular value or precept systematically represented in the text as an expression of the reign and rule of God? Or is this value limited to a marginal representation in the Bible via the particularities of situational ethics? To make an argument that environmental concern is a kingdom value the issue must rise to the level of the former—a consistent component of God’s instructions to humanity, a regular attribute of God’s communicated values and affections. That is what The Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters attempts to do, offer a biblical theology of creation care. Short and accessible, the objective is to give the Church a biblical argument. And as all biblical theology starts in Eden, this inquiry begins there as well.

What Does the Bible Say?

In the opening chapter of Genesis, God reveals his blueprint for creation. A close reading demonstrates that the questions the biblical author is attempting to answer are Who is God? What is humanity? And where do we all fit within this cosmic plan? In figure 1, we see that the reader is offered an answer to these questions via the literary framework of a perfect “week.” Here the interdependence of the cosmos is laid out within seven days of creative activity, crowned by the final day, the Sabbath. Thus, on days one through three we are offered three habitats (or kingdoms): (1) the day and night, (2) the sea and heavens, and (3) the dry land. On days four through six, the inhabitants (or rulers) of these various realms of creation are put in their proper places: (4) the sun and moon to rule the day and night, (5) the fish and birds to occupy the sea and sky, and (6a) the creatures who inhabit the dry land.1

The relationship between the first three and last three days of Genesis’ creation song communicates place and authority. Thus, on day four God creates the “two great lights” to “govern” (or “be lord of”; Hebrew māšal) the day and night (Gen 1:14–19). On day five fish and birds are created to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” the seas and skies (Gen 1:20–23). On day six the land creatures are created to occupy the dry land (Gen 1:24–25).

But as we approach the sixth day, we find that the literary structure shifts dramatically. Even the most casual reader can see that this day is given the longest and most detailed description up to this point. Why so much attention? Because this penultimate climax of Genesis 1 offers us the most breathtaking aspect of the Creator’s work so far. On this day a creature is fashioned in the likeness of the Creator himself—humanity (ʾādām) is created in the image of God.

Then God said, “Let us make humanity [ʾādām] in our image [ṣelem], according to our likeness; so that they may rule [Hebrew rādâ]2 over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” (Gen 1:26)

The profound implications of humanity (ʾādām) being fashioned and animated as God’s physical representatives on this planet cannot be overstated.3 Like the animated idols of Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts, humanity is a ṣelem (image), the animate representation of God on this planet. In essence, woman and man are the embodiment of God’s sovereignty in the created order. Here male and female are appointed as God’s custodians, his stewards over a staggeringly complex and magnificent universe, because they are his royal representatives. Like the fish and birds, humanity is commanded to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” their habitat. But because they are the image bearers of the Almighty, they are also commanded to “take possession of” (Hebrew kābaš), and “rule” (Hebrew rādâ) all of the previously named habitats and inhabitants of this amazing ecosphere as well:

God blessed them; and God said to them, “Be fruitful, multiply, and fill the earth so that you may take possession of it [kābaš].4 Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the heavens and every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Gen 1:28)

In the language of covenant, Yahweh has identified himself as the suzerain and ʾādām as his vassal. Moreover, Yahweh has identified Eden as the land grant he is offering to ʾādām. The final stanza introduces the ultimate climax of both the week and the message—the Sabbath day (Gen 2:1–3). This seventh day is set apart. It is sacred; it is holy. This day communicates that the universe in all of its breathtaking symmetry is finished, that the Creator is pleased. God has seated himself on his throne to revel in the beauty before him. Most important to us, the seventh day answers the question, “Who is in charge here?” The answer? The perfect balance of this splendid and synergetic system is dependent on the sovereignty of the Creator.5 And as God is enthroned over all the vastness of our universe on the seventh day, humanity’s installation on the sixth day announces that man and woman have been appointed as second in command, God’s stewards over this vast cosmos. This message is reiterated in Psalm 8, when a worshiper standing millennia beyond the dawn of creation reiterates the wonder of humanity’s position in the cosmos:

When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon, and the stars that you have fixed in place.

What is humanity that you should remember him?

Or the son of ʾādām that you should care for him?

You have made them [humanity] a little lower than the angels

and crowned them with glory and splendor,

You have made them lord [Hebrew māšal]6 over the works of your hands,

You have placed everything under their feet

Flocks and oxen, all of them!

Even the wild creatures of the field!

The birds of the heavens, and the fish of the sea,

whatever passes through the paths of the seas!

O Yahweh, our Lord,

how majestic is your name in all the earth. (Ps 8:3–9)

The message in both texts is explicit. Whereas the ongoing flourishing of the created order is dependent on the sovereignty of the Creator, it is the privilege and responsibility of the Creator’s stewards (that would be us) to facilitate this ideal plan by ruling in his stead. How? Like the other inhabitants of the earth, sky, and sea, the children of Adam are to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” the earth. But as the ones made in God’s image, we are also given authority over land and sea and sky and all their creatures. And like any vassal who has been offered a land,7 humanity is commanded to “take possession” of this vast universe per the instructions of his sovereign lord (Gen 1:28).8 In sum, humanity plays a critical role in God’s blueprint for the flourishing of this majestic ecosphere in which we find ourselves. Yahweh is indeed the ultimate sovereign, but humanity has been created as God’s representative to serve as custodian and steward enacting the Creator’s will by living out our vocation as a reflection of God’s image. We rule as he would rule. We are stewards, not kings.

Genesis 2:15 specifies humanity’s task further:

Then Yahweh Elohim took the human and put him into the garden of Eden to tend it [lĕʿobdâ]9 and to guard it [lĕšomrâ].10

In this second creation account, the message is repeated: the garden belongs to Yahweh, but human beings have been given the privilege to rule and the responsibility to care for this garden under the authority of their divine lord. This was the ideal plan—a world in which humanity would succeed in building their civilization by directing and harnessing the amazing resources of this planet under the wise direction of their Creator. Here there would always be enough. Progress would not necessitate pollution. Expansion would not require extinction. The privilege of the strong would not demand the deprivation of the weak. And humanity would succeed in this calling because of the guiding wisdom of their God. As I am wont to say in my classes, God’s ever-expanding universe was offered to his children such that they might always be captivated by its profound complexity, its fierce beauty, and its fragile balance. We were designed to love what God loves, and we were commissioned to seek the stars.

But we all know the story: humanity rejected this perfect plan and chose autonomy instead. And because of humanity’s position within the created order, all creation paid the price for humanity’s choice. Because of ʾādām, “the creation was subjected to futility” (Rom 8:20),11 “unable to attain the purpose for which it was created.”12 In an instant, God’s perfect world became ʾādām’s broken world—full of conflict, want, death, anxiety, and violence. And because of humanity’s strategic place in God’s plan, this twisted existence became the inheritance of all placed under humanity’s rule.

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul reflects on the impact of humanity’s sin on the cosmos and the glory of the world to come.

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that is to be revealed to us. For the anxious longing of the creation waits eagerly for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now. And not only this, but also we ourselves, having the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting eagerly for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our body. (Rom 8:18–23 NASB)

Paul speaks of all creation anxiously longing for “the revealing of the sons [heirs] of God” (Rom 8:19). Why does creation wait? Because “creation has been unable to attain the purpose for which it was created.”13 The ʾădāmâ (the “ground” in your translation) was subjected to ineffectiveness because of the rebellion of ʾādām (do you see the word play?). God’s chosen steward rebelled against his sovereign, and so the Garden has rebelled against him and is now trapped in the same self-defeating cycle as we are—“slavery to corruption” (v. 21). So just like the heirs of the kingdom, creation awaits its deliverance.

Thus, this passage offers us a poignant presentation of the great arc of redemptive history. As I often tell my students, redemption doesn’t start in Matthew 1:1 or even in Romans 3:23. It starts “in the beginning,” and concludes with the “a new heaven and a new earth” in which the river of life is once again free to flow and the tree of life graces its banks (Rev 21:21; 22:1–2). Redemption isn’t just about getting you or me into heaven (no fire insurance here!). Redemption is about restoring all creation. When the Last Adam returns, the chaos of the first ʾādām’s rebellion will be redeemed—the curse lifted, the cosmos liberated, and the earth healed from the effects of humanity’s sin (1 Cor 15:45). God’s ideal design for creation, as detailed in Genesis 1, will be restored. This very earth healed of its scars and washed clean of its diseases—just like the resurrected children of Adam (Rom 8:22–23). In other words, the redemption of this planet is built into the master plan.

The epic of Israel advances the same story. Like Eden, the “promised land” is a land grant—a fiduciary trust. The Mosaic covenant required that the flora and fauna of that land be stewarded with care. Sustainable agriculture was required.14 Exploitation of the wild creature or its habitat was forbidden.15 Abuse of the domestic creature was prohibited.16 Environmental terrorism was banned.17 Short term, desperation management that exhausted current resources in answer to the cry of the urgent was simply not acceptable in the theocratic government of ancient Israel. Even though this nation spent most of its existence on the razor’s edge of a subsistence economy, where the margin between “enough” and starvation was often imperceptible, Israel’s obedience to these covenantal mandates resulted in not only their personal economic success, but the long term care of the widow and the orphan as well.18 If this was Israel’s law as a landed people in the midst of a fallen world, what should ours be?

What Will We Say?

In my opinion, environmental stewardship is one of the most misunderstood topics of holiness within the Christian community. As I have traveled, written, and spoken on this topic in Christian circles for the last decade, I have found the Church largely paralyzed on this topic. Why is this? Why has the Church, the historic moral compass of our society, gotten so lost on such an important topic?

As I detail in Stewards of Eden, one reason is clearly politics. In America, the traditional political allies of the Church are not those of environmental concern. If you are pro-life, supposedly you cannot also be pro-environment. If you are a patriot, you cannot also be a conservationist. Thus, if you are a Christian, supposedly you cannot also be an environmentalist. But as citizens of the kingdom of heaven, the politics that direct the Christian’s life should not simply be those of his or her nation. Rather they must be the politics of the Kingdom. And in God’s kingdom, we are lessees not lessors. This planet and all its bounty are not ours; they are his. And he expects his property to look as good when he returns as it was when the lease was issued.

A second reason for our current paralysis is common to many issues of social justice—we the western majority voice are largely sheltered from the impact of environmental degradation on the global community. We don’t see how unregulated use of land and water by big business erodes the lives of the marginalized. Our front windows don’t overlook the decimation of the Appalachian mountains devastated by Mountain-Top Removal coal mining.19 The sterilization of fertile fields of Punjab, India at the hands of unrestrained industrial agriculture has not made its way into our newsfeed.20 The impact of untreated industrial chemicals and raw sewage on the Ganges River system that has rendered its future (in the words of the United Nations) as a “living system” unlikely is not our personal experience. We have not seen the images of Madagascar, where 88% deforestation has left the marginalized without recourse. So we often struggle to understand the issue of creation care as an expression of concern for “the widow and the orphan.”

Third, and perhaps most detrimental, is that we have been taught that the created order is bound only for destruction.

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief, in which the heavens will pass away with a roar and the elements will be destroyed with intense heat, and the earth and its works will be burned up. (2 Pet 3:10 NASB)

The resulting assumption is that it is ethically appropriate to use the earth’s resources as aggressively as possible to accomplish what really matters—the conversion of souls. This would be a logical response if the earth were indeed destined only for annihilation. But as Ben Witherington, Richard Bauckham, G. K. Beale, and Douglas Moo tell us, planetary annihilation is not God’s final intent. Rather, the images and metaphors employed in this passage and others like it (Mark 13:24–26; 1 Thess 5:2–3; Rev 6:12–17; Rev 21:1) are the stock typology of apocalyptic literature predicting judgment. Signs in the heavens and on earth, fire, and earthquake are all deployed throughout the Old Testament to describe the “Day of Yahweh,” throughout the New Testament to describe the Parousia.21 This is of course the day when Yahweh returns to this planet to reclaim the land grant. And although the continuity between this present world and the one to come is not fully understood, Rom 8:18–23, as well as Rev 21:1 and 22:1–2, make it crystal clear that God’s intention for this planet is not to annihilate it, but to redeem it.

In my experience, the body of Christ readily recognizes the disastrous effects of the fall in the arena of human relationships. Corrupt and abusive governments, bigotry and violence, the oppression of the weak and the deprivation of the voiceless—no one needs to tell the informed believer that these realities were not God’s original intent for humanity. Nor, in my experience, does anyone need to tell the committed Christian that it is the responsibility of the church to take a proactive stand against these distortions of God’s good plan. History teaches us that, at its best, the church has been among the first to identify the effects of the fall on human society and has often been the first to respond. But rarely, it seems, do we as Christians reflect on the effect of humanity’s rebellion on the garden. And rarely, it seems, do we consider how the reality of redemption in our lives should redirect our attitude toward the same.

Surely if the ultimate objective of our God is to reconcile the world to himself through us (2 Cor 5:17–21), the topic of environmental stewardship deserves to be on the table. And if the role of the redeemed community is to live as an expression of another kingdom—as Adam and Eve should have, as Jesus Christ has—how can we avoid this message that it is our responsibility as redeemed humanity to live in such a way that the intentional stewardship of God’s creation is evident in our lives? The apostle Paul says that our calling is to offer ourselves in worship to God, to discern and embrace “what the will of God is, that which is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom 12:2). And what is the will of God regarding creation?

Then Yahweh Elohim took the human and put him into the garden of Eden to tend it [lĕʿobdâ] and protect it [lĕšomrâ]. (Gen 2:15)

Adapted from Stewards of Eden by Sandra L. Richter. Copyright (c) 2020 by Sandra L. Richter. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com.

Sandra L. Richter is the Robert H. Gundry Chair of Biblical Studies at Westmont College. Richter earned her PhD from Harvard University’s Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Department and her MA in Theological Studies from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. She is well known for her book The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament (IVP) and her work on the intersection of Syro-Palestinian archaeology and the Bible. She has taught at Asbury Theological Seminary and Wheaton College, is in high demand as a speaker in an array of academic and lay settings, and is currently serving on the NIV translation committee. You can learn more about her most recent book, Stewards of Eden, in this video introduction.

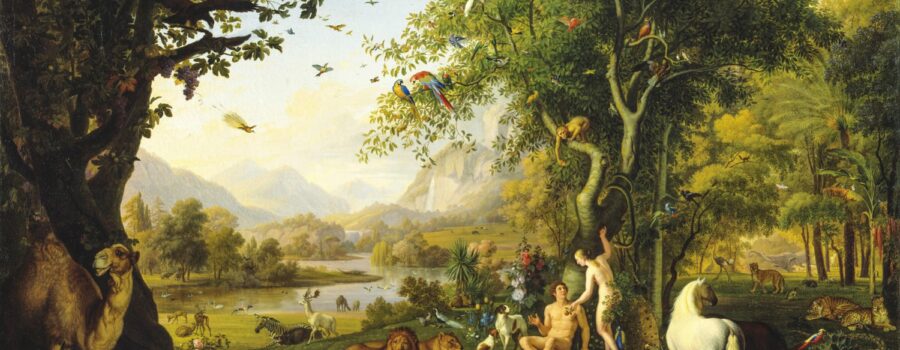

Image: Johann Wenzel Peter, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

- See Sandra Richter, The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008), 92–118; Meredith G. Kline, Kingdom Prologue: Genesis Foundations for a Covenantal Worldview (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 38–43.[↩]

- HALOT, s.v. “רדה,” p. 1190. Although most often translated “to rule,” the argument has been made that “the basic meaning of the verb . . . actually denotes the travelling around of the shepherd with his flock” (ibid.; cf. Lev 25:43, 46, 53; Num 24:19; and 1 Kings 5:4).[↩]

- See Catherine McDowell, The Image of God in the Garden of Eden: The Creation of Humankind in Genesis 2:5–3:24 in Light of the mīs pî, pīt pî, and wpt-r Rituals of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, Siphrut 15 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2015), and Sandra L. Richter, The Epic of Eden: Isaiah, A One Book Curriculum (Franklin, TN: Seedbed, 2016).[↩]

- HALOT, s.v. “כבש,” p. 460. “Subjugate” is a typical translation of this verb. It is found throughout the Bible in contexts in which a people group or conquering army has moved into new territory and taken possession of it (e.g., Num 32:22, 29; Josh 18:1; 2 Sam 8:11). For example, David asks his cabinet, “Has God not given you rest on every side? For He has given the inhabitants of the land into my hand, and the land is subdued [kābaš] before the Lord and before His people” (1 Chron 22:18 NASB). This verb is typically used regarding land, not animate creatures.[↩]

- See Kline, Kingdom Prologue, 38.[↩]

- HALOT, s.v. “משל,” pp.647–8; when combined with the preposition בְ this verb communicates placing someone into an office of authority (Dan 11:39).[↩]

- Richter, Epic of Eden, 69–91.[↩]

- For kābaš utilized with a land grant, see n. 4 as well as Josh 18:1 and 2 Sam 8:11.[↩]

- HALOT, s.v. “עבד,” p. 773. The most essential meaning of this verb is “to serve; to work.” When in the context of cultivatable land, it is typically translated “to till”; when with an animal, “to work with.”[↩]

- HALOT, s.v. “שמר,” pp. 1581–4.[↩]

- See Douglas J. Moo and Jonathan A. Moo, Creation Care: A Biblical Theology of the Natural World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 147–52 for further discussion.[↩]

- Douglas J. Moo, “Nature in the New Creation: New Testament Eschatology and the Environment,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 49 (2006): 461.[↩]

- Moo, “Nature in the New Creation,” 461. “The ‘vanity’ to which creation was subjected would appear to refer to the lack of vitality which inhibits the order of nature and the frustration which the forces of nature meet with in achieving their proper ends” (Murray, Epistle to the Romans, 303); cf. William Sanday and Arthur C. Headlam, The Epistle to the Romans, 4th ed., International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1900), 205.[↩]

- Sandra Richter, Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2020), 5–14.[↩]

- Ibid., 48–59.[↩]

- Ibid., 29–47.[↩]

- Ibid., 60–66.[↩]

- Ibid., 67–81.[↩]

- Ibid., 81–90.[↩]

- Ibid., 24–28.[↩]

- Richter, Stewards of Eden, 91–100; cf. Ben Witherington III, The Indelible Image: The Theological and Ethical Thought World of the New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 1:797–805; Richard Bauckham, Jude, 2 Peter, Word Biblical Commentary 50 (Waco, TX: Word, 1983), 299; Bauckham, “Jesus and the Wild Animals (Mark 1:13): A Christological Image for an Ecological Age,” in Jesus of Nazareth: Essays on the Historical Jesus and New Testament Christology, ed. Joel B. Green and Max Turner (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 4; G. K. Beale, “The Eschatological Concept of New Testament Theology,” in “The Reader Must Understand”: Eschatology in Bible and Theology, ed. K. E. Brower and M. W. Elliott (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1997), 11–52; James D. G. Dunn, A Theology of Paul the Apostle (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 101.[↩]