Tremper Longman III

We live in a fallen world. Still, while broken, we glimpse the beauty of God’s creation. We are fallen people. Nonetheless, while sinners, humans bear the image of God and reflect his glory, though dimly.

As fallen people living in a fallen world, we experience various forms of suffering in our personal and our corporate lives. No one escapes suffering, including Christians. The promise of the gospel is not to remove us from suffering, but to preserve us through suffering in Christ, which empowers us to suffer in hope and with joy.

Peace amid Peril?

That is the point that the apostle Peter is making to his contemporaries, who lived in a culture that was much more toxic to Christianity than our culture is today, at least for those of us living in the West.

In all this you greatly rejoice, though now for a little while you may have had to suffer grief in all kinds of trials. These have come so that the proven genuineness of your faith—of greater worth than gold, which perishes even though refined by fire—may result in praise, glory and honor when Jesus Christ is revealed. Though you have not seen him, you love him; and even though you do not see him now, you believe in him and are filled with an inexpressible and glorious joy, for you are receiving the end result of your faith, the salvation of your souls. (1 Peter 1:6–9)

Is the church today reflecting the joy and hope in the midst of suffering about which Peter writes?

My impression is that she is not. Rather than joy and hope, I see, hear, and read expressions of relentless fear and anger. This fear and anger, at least among some vocal American Christians, is directed toward the so-called secular culture and its political and intellectual elites, whom they believe are eroding the Christian values on which they suppose our country was founded. They see the legalization of abortion and same-sex marriage as well as the diminishment of religious liberty as dangers to the faith. Public expressions of fear and anger from Christians are common in public places.

Today, these issues are compounded by fear of a pandemic that rages throughout the world, a pandemic that has led to unparalleled economic devastation. People on ventilators. Lost jobs. Stuck in our rooms. Wearing masks.

Shouldn’t Christians be anxious and even angry?

Peter, it seems, would say no, we shouldn’t—because our reactions to the testing of these trials prove the genuineness of our faith. If we persist in fear and anger rather than joy, then we fail to grab hold of the reality of God’s promises and even cast doubt on our salvation. If we abide in fear and anger, then the watching world will be repulsed by rather than attracted to our faith.

But, let’s be honest, fear and anger are real emotions. Joy and hope are indeed hard to come by in the midst of lost jobs and pending disease. How do we cope?

Thank God that he has given us a way to process our fear and anger through turning to him in prayer. Indeed, he has given us a powerful collection of prayers that can serve as a template for our own prayers in the midst of struggle—the book of Psalms.

John Calvin famously called the book of Psalms a mirror of the soul. He put it this way:

The varied and resplendid riches which are contained in this treasury it is no easy matter to express in words…. I have been accustomed to call this book, I think not inappropriately, “An Antatomy of all the Parts of the Soul;” for there is not an emotion of which any one can be conscious that is not here represented as in a mirror.1

Not a single emotion that we feel is absent from the psalms, and that includes fear and anger. How do the psalms express our fears and our anger in a way that leads to joy and hope?

Giving Anger to God

We first turn to a group of psalms that the prolific and insightful biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann called psalms of disorientation.2 Laments are psalms that we pray when life is confused, crazy, troubled. There are different types of laments, but some of the most powerful are those that express anger. The psalmists clearly are angry with those who have harmed them as well as God himself.

Take Psalm 69 as an example. The psalmist starts by crying out in pain, “Save me, O God, for the waters have come up to my neck” (v. 1). He goes on to speak about those who are bringing suffering into his life: “Many are my enemies without cause, those who seek to destroy me” (v. 4). Indeed, the psalmist believes he suffers at their hands because of his devotion to God: “For I endure scorn for your sake” (v. 7).

While he expresses his desire for God to rescue him, he also tells God he wants him to harm his enemies. He wants God to punish them for what they have done to him:

May the table set before them become a snare;

may it become a retribution and trap.

May their eyes be darkened so they cannot see,

and their backs be bent forever.

Pour out your wrath on them;

let there be no one to dwell in their tents.

For they persecute those you wound

and talk about the pain of those you hurt.

Charge them with crime upon crime;

do not let them share in your salvation.

May they be blotted out of the book of life

and not be listed with the righteous. (69:22-28)

Many Christians balk at this kind of imprecatory language in the psalms, but if we are honest, we ourselves have felt this passion toward others—the person who let us go, the person who may have infected us with the virus (or the country from which it came), the secularist who wants to remove our religious freedom, the politician who instituted a policy with which we disagree.

But notice what the psalmist is doing here (and there are a number of laments which contain these types of imprecations). He is not saying, “God, give me the resources and the opportunity to hurt my enemies!” No, he is rather saying, “God you hurt them!” And there is a world of difference here. The psalmist is turning his anger over to God. God will do what he will do in response to the harm done to us. In essence, what the psalmist does is in keeping with Paul’s later admonition to those who are angry: “Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: ‘It is mine to avenge; I will repay,’ says the Lord” (Rom 12:19).

Interestingly, as is well known, almost all of the laments, including those with these hard-hitting imprecations, end with statements of confidence or joy. This generalization includes Psalm 69, which concludes with a section of praise that begins, “I will praise God’s name in song and glorify him with thanksgiving” (v. 30). Though this transformation certainly took place over a period of time and not in a second, the psalmist was able to work through his anger to a place of joy in the midst of suffering.

Confidence in Tribulation

There is another type of psalm which is particularly helpful as we struggle through our pain to a place of joy and hope. And these are psalms of confidence.3

Brueggemann, whose work was mentioned above, insightfully points out that the psalms have prayers that are appropriate for those times when God answers our laments. They are psalms of reorientation or thanksgiving prayers (for example, Psalm 30). And then, ultimately, we return to a time of orientation where we sing hymns again (for example, Psalm 24 or 98).

But what happens if God does not answer our laments? Here we might consider psalms of confidence, psalms that we sing in spite of our continued suffering. These express the type of attitude Peter claims that Christians should hold in our suffering world.

In Psalm 23, the composer announces, “Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I will fear no evil for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me” (v. 4). Later we hear him say to God, “You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies.” Or we might also consider Psalm 131 where the psalmist in the face of threat says, “I have calmed and quieted myself, I am like a weaned child with its mother; like a weaned child I am content,” (131:2) after which he then turns to the congregation to exhort them to “put your hope in the Lord both now and forevermore” (v. 3).

Praying toward Peace

In spite of the false claims of some that faith always leads to health and wealth, God does not promise that his people will escape the suffering of the world. So what differentiates Christians from others in a world of pain and suffering? Again, we return to Peter. We suffer not in anger and fear, but in joy and confidence. We turn our anger and fear over to God in prayer, and as we put our trust in him, we can experience that “peace of God, which transcends all understanding” (Phil 4:7) which the gospel brings. The world will then know us not by our anger and our hate, but rather by our love, and by that love the world will know that we are God’s (John 13:35–36).

Tremper Longman III (B.A., Ohio Wesleyan University; M.Div., Westminster Theological Seminary; M.Phil. and Ph.D., Yale University) is Distinguished Scholar and Professor Emeritus of Biblical Studies at Westmont College. His most recent books are Confronting Old Testament Controversies: Pressing Questions about Evolution, Sexuality, History, and Violence (Baker, 2019), The Bible and the Ballot: Using Scripture for Political Decisions (Eerdmans, 2020), and How to Read Daniel (InterVarsity Press, 2020). His books have been translated into seventeen different languages. He is one of the main translators of the popular New Living Translation of the Bible. His website may be found at tremperlongman.com.

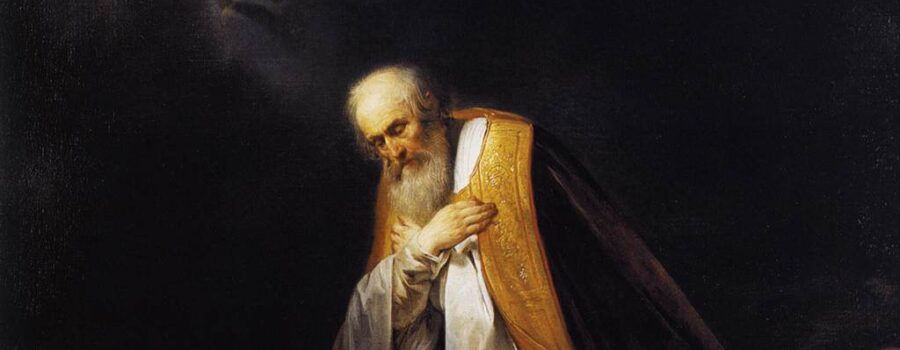

Image: Pieter de Grebber, King David in Prayer

- John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, trans. James Anderson, Calvin’s Commentaries 4 (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 2005), 1:xxxvi–xxxvii.[↩]

- Walter Brueggemann, The Psalms and the Life of Faith, ed. Patrick D. Miller, Jr. (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1995), 3–32.[↩]

- For a helpful study of psalms of confidence, see Glenn Pemberton, After Lament: Psalms for Learning to Trust Again (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 2014).[↩]