David T. Koyzis

Someone recently posed a question on social media that, in my estimation, warrants a considered response: Would the Dutch polymath and statesman Abraham Kuyper wear a MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) hat? In other words, would Kuyper endorse the nationalism, especially the so-called Christian Nationalism, that has overtaken a large portion of the American electorate and has supported the presidency of Donald J. Trump?

I don’t believe this is difficult to answer. Although some fans of Kuyper have embraced the MAGA agenda and have enlisted his name and reputation in its support, I do not believe that he would approve. Why?

To begin, any form of nationalism is based on making too much of a genuine good, namely, nation and loyalty to nation. I discuss nationalism at some length in chapter 4 of Political Visions and Illusions under the title: “Nationalism: The Jealous God of Nation.” Each of the ideologies I cover in that book is based on taking something good out of God’s creation and elevating it to the status of a pseudo-god. Furthermore, each, with the partial exception of conservatism, is based on a redemptive narrative that mimics the biblical story of salvation. I explain this in some detail as follows. The nationalist redemptive story

generally runs along the following lines: The nation has existed from time immemorial, established perhaps by the gods or by God and given a particular historical mission to work out. But at some point the nation departs from its calling and falls under the oppressive rule of another people, perhaps a neighboring nation or a multinational empire. It may disappear completely or be scattered to the four winds, where it exists as a diaspora among other peoples, struggling to maintain its distinctive character. At some point, salvation comes when a national leader or a group of leaders rise up and throw off the yoke of oppression. Or they may gather the diaspora from exile and resettle their ancient homeland, where they can resume their way of life as a people. In such cases salvation is either explicitly or implicitly identified with liberation from the alleged tyranny of a foreign nation.

The similarity to the biblical redemptive narrative is, of course, unmistakable. God selects his own people from among the other peoples of the world, guiding them to the Promised Land. He establishes a covenant relationship with them, charging them with keeping his commandments. But they disobey and are punished by their pagan neighbors, who oppress them for a time. When the chosen people repent of their evil ways and call on God to help them, he sends a prophet to liberate them—from slavery in Egypt or from exile in Mesopotamia. He guides them back to the land, and the covenant is renewed. Finally God sends his own Son to take on the people’s sins and offer his saving grace once for all, to be followed by the final advent of God’s kingdom in its fullness. Nationalists, especially those whose culture had been shaped in some fashion by the Bible, easily adapt this story for their own purposes, assuming that God has chosen them for a special task.1

Although Christians throughout the world have fallen prey to this form of nationalism, Americans have been especially vulnerable to this treatment due to what might be called a secularized form of the old Puritan faith of New England, with its emphasis on what John Winthrop hoped would become a “city upon a hill” in a famous 1630 sermon. It has thus been easy for many Americans to take the biblical covenant between God and Israel and apply it to the American national community, even as they are unaware of the perils of so doing. The result is an ersatz religion that seeks an earthly salvation through human effort and places confidence in a messianic figure promising to lead them to the promised land.

This in large measure explains the somewhat lopsided focus on immigration in the current administration. A nation requires a certain degree of homogeneity if it is to achieve greatness. Less homogeneity implies greater disagreement, not only on policy matters, but even on the overall vision animating the nation. Greatness calls for greater unity of purpose, which will necessarily be lacking in a diverse population. If this diversity cannot be eliminated outright, we can at least try to limit it or perhaps, if possible, even suppress it. The United States has periodically seen outbursts of nativism since its founding. We are witnessing one now, and it will probably not be the last, even if this one proves to be short-lived.

By contrast, if we were to view our own national communities more modestly—namely, as explicitly political communities constrained by the ordinary limits of politics and by a patriotic loyalty guided by the norm of public justice—we would be far less likely to succumb to the fears engendered by those trying to protect or advance an artificial uniformity. As I see it, there are several reasons to avoid the nationalist temptation, reasons flowing out of this pseudo-redemptive narrative.

1. Nationalists tend to view the nation as an all-encompassing community of which other communities are mere parts. Although not all nationalists are totalitarian in the full sense, living out their convictions consistently in the policy process has definite totalitarian implications. This in turn leads to an overestimation of the role of politics, or perhaps more properly the state itself, and what it can accomplish in facilitating national unity.

2. Nationalists seek to homogenize a diverse population and a pluriform society and to press them into a single mold. In so doing, they are following a blueprint drawn up by the architects of other ideological visions, for whom diversity of perspectives and even a plethora of nonstate communities are viewed as threats. For many nationalists, the achievement of national greatness may necessitate suppressing those communities deemed to obstruct this larger goal. And the state is the chosen instrument to make it happen.

3. Nationalists therefore esteem politics too highly and assume it can be made an instrument, not of public justice, but of the popular will. Once again, this is not peculiar to nationalism. It is also true of democratism, which I cover in chapter 5 of Political Visions, and even of liberalism (chapter 2) and socialism (chapter 6) to a great extent. If we trace the history of liberalism, for example, back to the social contract theories of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, we can see that political community is a mere agreement amongst self-interested individuals fulfilling their own subjective aspirations rather than a community normed by public justice.

4. Especially under the current administration, this form of nationalism consists of bullying opponents into submission and overextending the limits of a nation—for example, by employing “fifty-first state” rhetoric against a neighboring country. That nationalism easily turns into imperialism should scarcely need to be pointed out, because it has happened again and again throughout the modern era. Today we can see it in Vladimir Putin’s designs against Ukraine, Viktor Orban’s use of the pre-1920 map of Hungary, and Trump’s threats against Canada and Greenland. That these last items have failed to make a dent in the President’s support base illustrates the power of a nationalist vision—or rather illusion—to deaden even common sense and otherwise good judgement

5. Ironically, although MAGA adherents make too much of politics, they evidently do not understand the political process in the real world and exhibit a striking naïveté concerning it. Building a consensus through patient negotiation and deliberation is, for ideologues, too slow. They prefer a strong man who will achieve their goals by decree from the top, even in the face of constitutional and legal standards and a polarized public. In short, they prefer to bypass ordinary politics and, as is typical of followers of an ideology, opt for autocratic means to reach their goals. Thus the paradox: while MAGA followers overestimate what politics can do, their lopsided focus on politics fundamentally misapprehends its true character.

6. This has implications for Christian Nationalists’ misuse of covenant theology. If the American nation is in a covenant relationship with God, along the lines of ancient Israel, we would then have to inquire which institution is responsible to enforce this covenant’s terms. A nation, especially when conceived in undifferentiated fashion, can never be a responsible agent but only an amalgam of pluriform social structures bound loosely together by certain common elements, such as shared culture and language. Yet generally the nationalist assumption is that this responsibility belongs to the state, viewed as the highest agent in that nation. This again makes entirely too much of the state as an institution, in addition to misapprehending its normative structure as led by public justice—a proximate justice falling well short of God’s final judgement.

As for the enlistment of Kuyper’s legacy for the MAGA agenda, many Christian Nationalists have gladly taken on Kuyper the warrior. Yes, there are battles to be fought within the political arena. Kuyper understood this only too well, and he was willing to court controversy in his efforts—in the churches, in journalism, in education, and in political life.

But Kuyper was also a conciliator, recognizing that his kleine luyden (literally “little people,” but perhaps better: “common folk”) were outnumbered by their fellow citizens who adhered to alternative worldviews. Somehow the orthodox Reformed Christians he led would have to live alongside their Roman Catholic, liberal, and socialist fellow citizens.

As such, Kuyper proved willing and capable of cultivating coalitions with leaders of these other communities for proximate political purposes that would benefit all citizens of the Netherlands irrespective of their ultimate convictions—something requiring patience and hard work. This is a reality that Christians captive to a nationalist ideology, who think they are carrying forward Kuyper’s legacy, have missed.

So, no, Kuyper would not wear the hat.

David T. Koyzis is a Global Scholar with Global Scholars Canada. He holds the Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame. He is author of Political Visions and Illusions (IVP Academic, 2019), We Answer to Another: Authority, Office, and the Image of God (Pickwick, 2014), and Citizenship Without Illusions (IVP Academic, 2024)..

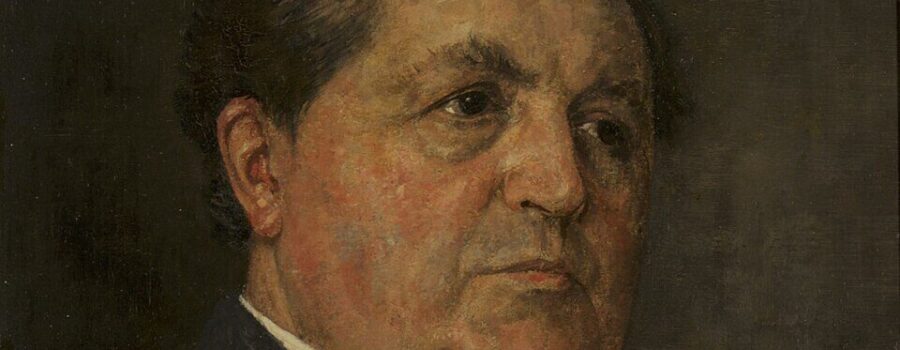

Image: Jan Veth, Portrait of Abraham Kuyper

- David Koyzis, Political Visions and Illusions: A Survey and Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2019), 98–99.[↩]