D. Glenn Butner, Jr.

The history of US immigration policy is rife with a denial of due process for migrants. There are many US laws that offer provisions for migrants to lawfully enter or remain in the country, sometimes even without a visa, but systems have consistently been in place to prevent these laws from being followed.

For example, in 1996, the Clinton Administration signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) which allowed for expedited removal (i.e., removal without trial) of migrants without papers.1 In the 2000s, the Bush administration launched Operation Streamline, which began mass trials of up to 70 migrants in a single shared hearing, with each individual having only moments to plead a case before a judge.2

Because many US immigration violations are considered a civil offense rather than a criminal offense, immigrants are technically not afforded constitutional protections for criminals such as guaranteed legal representation.3 Many migrants are not represented in court, or they rely on pro bono work from lawyers. In the 2010s, the Obama administration expedited hearings for children resulting in a dramatic increase of children not finding pro bono legal representation before trial. Their cases were decided without adult representation.4

Most recently, the Trump administration has deported or attempted to deport migrants without trial to third country prisons, where they will face incarceration of unknown lengths often in countries known for human rights violations. Denial of due process in the past has resulted in the deportation of US citizens, the detention of migrants who are lawfully present, and the deterrence of migrants who have a legal basis for entering the United States. Newer Trump policies risk widespread criminal incarceration of migrants with no criminal record or criminal activity.

In this article, I will argue that Protestant social ethics demands due process be given to migrants. But what does this term mean? I could point to many features of US law to define due process; for example the fourteenth amendment prohibits the “State [from] depriv[ing] any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”5 However, the term can also be taken more colloquially to refer to access to a fair legal process for determining innocence or guilt. Since I am not a lawyer, this is the meaning I will be using for the term in this article. Rather than weighing in on technical legal matters, this article will insist that migrants6 are owed a fair legal process for determining their innocence or guilt in terms of immigration law and criminal law. The nature of government and the nature of justice require that migrants have a fair legal process for determining innocence and guilt, especially given a robust theological anthropology that affirms both the image of God and the fallenness of humanity.

Due Process and the Purpose of Government

Due process is owed to migrants because of the nature and purpose of government. While earthly governments consistently fall short of God’s standards of justice, as Samuel warned the Israelites from the first days they asked for a king (1 Sam 8:10–18), God permits and establishes governments, in all their imperfections, so that they may work toward promoting justice. This pursuit of justice is one important component of government’s even broader charge to promote the common good.7 Romans 13:1–5 describes governments as God’s servants who punish the wrongdoer and do good to the innocent. Yet, to fulfill this purpose, the assumption is that the government must be able to discern who has done good and who has done wrong, a discernment that requires a process and the consideration of evidence. A government that denies a process through which it can discern innocence from guilt is a government that is fundamentally failing at its God-given purpose.

One might object that the government can know what immigrants have criminal violations or are illegally present without recourse to a trial. I have four concerns with this objection: First, governments make mistakes all the time, so a trial ensures that the government can prove its case to a judge or jury. Without a trial, surely more innocent people will be wrongfully punished. Second, while deportation without trial may seem justifiable given an obvious lack of papers for some migrants, US law and policy has many provisions which would allow these undocumented individuals to lawfully stay in the United States. Without a fair process allowing these individuals to present cases for asylum or other protective statuses like parole or Temporary Protected Status, the government is acting contrary to its own laws, undermining its purpose. Third, where simple deportation could be viewed as returning someone to where they lawfully belong, the Trump administration has been incarcerating individuals both in the United States (like the preceding administrations of Presidents Biden and Obama, for example) or abroad. Incarceration is a harsher punishment and so demands more robust scrutiny. Fourth, due process is a central aspect of the nature of justice, which leads to the second reason why migrants deserve due process.

Due Process and the Nature of Justice

The nature of justice itself provides a second reason why migrants deserve due process. The Christian tradition has long seen the virtue of justice as something oriented to all human beings. Thus, the Puritan William Ames explains that the object of justice is our neighbor. “This means everyone who is or may be a partaker with us of the same end and blessedness.”8 Much earlier, Augustine of Hippo similarly remarked, “Justice is the virtue which accords to each and every man what is his due.”9 It is the nature of justice that it is owed to all human beings, regardless of immigration status.

Justice has classically included several facets, especially (1) distributive justice, which pertains to the distribution of economic goods; (2) retributive justice, or justice in punishing; and (3) commutative justice, which gives each person what they are owed in particular interactions. The Old Testament law has clear teachings which would demand due process as a matter of retributive justice (e.g., incarcerating an immigrant) and commutative justice (e.g., directly considering the process owed to a migrant in legal matters).

Scripture is clear that migrants are owed due process. Consider Leviticus 19:34, which calls Israel to “regard the alien who resides with you as the native-born among you.” Immediately after this, Leviticus also insists on fairness in measurements (19:35–36), weighing and determining things honestly. Deuteronomy 1:16–17 is even more clear:

Hear the cases between your brothers, and judge rightly between a man and his brother or his resident alien. Do not show partiality when deciding a case; listen to small and great alike. Do not be intimidated by anyone, for judgment belongs to God.

Note how the justice of the judge is linked with the justice of God, who is clearly identified as impartial in judgment (Acts 10:34; Rom 2:11; Gal 2:6; 1 Pet 1:17). Justice is not an abstract idea, but a divine attribute to which we are called to conform. In its most basic, biblical form, due process demands that migrants be heard and impartially judged. This is a matter of justice.

Pragmatism can be an enemy of justice. One might object that it is unreasonable or infeasible to offer a trial to each of the millions of undocumented immigrants present in the United States, much less to each of the additional millions of migrants that are apprehended or turned away at the border each year. The demand for so many trials may not seem feasible. I admit that there is a certain eschatological dimension to Christian ethics.10 We await a kingdom of perfect justice that is only inaugurated, and so we must balance the justice we can already embody with the justice that has not yet appeared with the return of our Savior and King.

Even if I put on the mantle of the pragmatist for a moment, I must insist that there are great strides that can be taken toward the justice of due process in the US government. For example, the Bush and Obama administrations spent $7.6 billion from 2004–2009 on a “cyber-fence” consisting of radar, cameras, and motion sensors deployed along the southern border.11 This expense happened despite the fact that a prior project using the same technology had spectacularly failed during the Clinton administration, a fact known to many of the lawmakers who voted to fund the fence. The goal here was not establishing security but providing the illusion of security to attain votes. Had lawmakers pursued justice rather than the appearance of justice for the sake of gaining votes to preserve power, they could have easily redirected that $7.6 billion toward providing hearings for migrants. Given the many billions of dollars currently being redirected toward immigration apprehensions under the Trump administration, I am convinced that it is possible to also redirect enough money toward criminal and civil procedures for immigrants to make great strides toward offering due process.

Due Process and the Humanity of Migrants and Government Officials

Finally, migrants are owed due process because of who they are as human beings bearing the image of God (Gen 1:26–27) who, like all of humanity, are born in sin due to Adam and Eve’s fall (Gen 3; Rom 5:12–21). As human beings, migrants have an inherent dignity and worth that demand our respect, regardless of their immigration status. It’s true that the image of God in human beings does not give much specificity to our moral decision-making. After all, image-bearers can still be incarcerated or deported, for example, so bearing the image does not resolve questions about immigration enforcement. However, the inherent dignity of all human beings does explain why the Old Testament was particularly concerned to care for those who were vulnerable. Their dignity was more easily ignored, so special care was mandated for their protection. While many Ancient Near Eastern societies offered legal protection for groups like the poor, the orphan, and the widow, Israel was unique in also insisting on protections for the migrant (Deut 14:29; 16:11; 24:17–20; etc.).12 This addition was partly due to the inherently risky situation in which migrants found themselves, but special concern was also partly due to Israel’s experiences as oppressed foreigners in Egypt (e.g., Exod 22:21).

Human beings are also fallen. This means that some immigrants will deserve incarceration, deportation, or other penalization. A robust legal process ensures that the state prosecute such offenders as a matter of justice for the protection of the people. This role for the legal process is good! Evidence consistently shows that immigrants of any status are less likely to commit crimes, especially violent crimes, than citizens.13 This is likely in part due to the harsher sentences like deportation awaiting migrants but not citizens; criminal screening of immigrants before entry surely also plays some role.14

Yet, the fall extends to all human beings (Rom 3:23), migrant or citizen—including those tasked with maintaining justice. Calvin succinctly summarizes one result of the fall in his Instruction in Faith: “The intellect of man is indeed blinded, wrapped with infinite errors and always contrary to the wisdom of God; the will, bad and full of corrupt affections, hates nothing more than God’s justice.”15 Given these noetic and volitional effects of sin, which not only prevent us from knowing God but also from embodying the virtues of wisdom and justice, due process is extremely important.

A transparent process for trying migrants entices even a sinful, depraved heart toward justice. The vice of fear of consequences for acting unjustly may restrain unjust rulings when hearings are in public, while the vice of vainglory may lead an indifferent judge or jury toward acting justly, not out of virtue, but selfishly seeking affirmation and applause. When trials proceed in secret, sin is more likely to distort just rulings. Therefore, the Christian ought to advocate for due process for migrants as a necessary dimension of justice befitting the purpose of the state and protecting the migrant who bears God’s image while still allowing for prosecution for those guilty of crimes.

In light of these moral principles, presidential administrations for decades have failed to live up to biblical standards and can rightly be critiqued. The escalation of suspension of due process for migrants under the Trump administration deserves even more forceful condemnation. To such acts the prophet Isaiah still speaks today: “Woe to those who call evil good . . . who acquit the guilty for a bribe, and deprive the innocent of his right!” (Isaiah 5:20, 23).

Glenn Butner is Associate Professor of Theology at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, MA. He writes in dogmatic theology and social ethics, including Jesus the Refugee (Fortress Press, 2023) and a forthcoming book tentatively titled Christians and Borders. He attends First Congregationalist Church of Hamilton and has served in nonprofits, chaplaincy, and in ministry with displaced migrants.

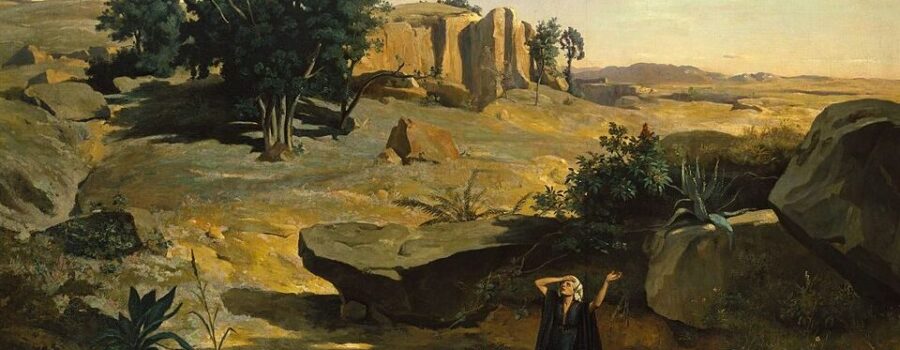

Image: Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Hagar in the Wilderness

- María Christina García, The Refugee Challenge in Post-Cold War America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 120.[↩]

- See Joanna Lydgate, “Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline.” (Berkeley, CA: Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity & Diversity, 2010) Accessed online, July 12, 2025: https://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/Operation_Streamline_Policy_Brief.pdf.[↩]

- Mark R. Amstutz, Just Immigration: American Policy in Christian Perspective (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2017), 44.[↩]

- Linda Dakin-Grimm, Dignity & Justice: Welcoming the Stranger at Our Border (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2020), 11.[↩]

- Note that the phrase “any person”—this is not a principle for citizens alone.[↩]

- I use the term “migrant” rather than immigrant because there are many individuals who are present in the United States, both lawfully and unlawfully, who are not technically immigrants because they do not have permission to settle here, but who nevertheless are temporary residents who might face incarceration, deportation, or other penalties. “Migrants” thus covers expansive groups like lawful permanent residents, refugees, parolees, recipients of temporary protected status, tourists, and undocumented immigrants.[↩]

- On government’s charge to protect the common good, see Bradford Littlejohn, “The Civil Magistrate,” in Protestant Social Teaching: An Introduction, ed. Onsi Aaron Kamel, Jake Meador, and Joseph Minich (Davenant Press, 2022), 30–41.[↩]

- William Ames, The Marrow of Theology, trans. John Dykstra Eusden (Durham: Labyrinth, 1968), II.16.3. Emphasis added.[↩]

- Augustine of Hippo, City of God,abridged version, trans. Gerald G. Walsh, Demetrius B. Zema, Grace Monahan, and Daniel J. Honan, ed. Vernon J. Bourke (New York: Doubleday, 1958), 19.21. Emphasis added.[↩]

- This is so much the case that Richard Hays has identified eschatology and the new creation as one of three focal images summarizing the entirety of Christian ethics. See Richard B. Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament: A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1996).[↩]

- Robert Lee Maril, The Fence: National Security, Public Safety, and Illegal Immigration Along the U.S.–Mexico Border (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), 177. Maril’s book offers a lengthy and detailed account of the recurring folly of a high-tech border fence.[↩]

- Christiana Van Houten, The Alien in Israelite Law, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplemental Series 107 (JSOT, 1991), 34–35.[↩]

- For a survey of this data, see D. Glenn Butner, Jr., Jesus the Refugee: Ancient Injustice and Modern Solidarity (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2023), 100–9.[↩]

- It is worth noting that overstaying a visa is not actually a crime but merely a civil offense. Estimates vary, but some think as many as half of undocumented immigrants have overstayed a visa.[↩]

- John Calvin, Instruction in Faith (1537), trans. and ed. Paul T. Fuhrmann (Westminster John Knox, 1977), 25.[↩]