David T. Koyzis

Most standard Protestant hymnals include Samuel J. Stone’s classic hymn “The Church’s One Foundation,” sung to the memorable tune, AURELIA, composed by Samuel Sebastian Wesley, grandson of Methodist founder and hymn writer, Charles Wesley. One of the hymn’s less sung stanzas testifies to the controversy that led Stone to write it:

Though with a scornful wonder,

men see her sore oppressed,

by schisms rent asunder,

by heresies distressed,

yet saints their watch are keeping;

their cry goes up, “How long?”

And soon the night of weeping

shall be the morn of song.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Anglican Bishop of Natal, John Colenso, caused controversy in the South African church when he publicized his doubts on the eternal punishment of the unsaved and questioned the historicity of episodes recounted in the Bible. This prompted Stone to write his famous hymn in 1866.

Although some may think that controversies within the church are a recent phenomenon, a reading of both the New Testament and subsequent church history will quickly reveal that church splits have been with us since the beginning. The major themes of these controversies have come at approximately semi-millennial intervals, revolving first around Christology, then ecclesiology, then soteriology, and finally anthropology.

Christology

First, Christology. After the coming of Jesus Christ and the foundation of the Christian church in AD 33, the gospel spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire and beyond. It has been suggested that the first region to boast a Christian majority was western Asia Minor—present-day Turkey—the location of the seven churches to which the author of the Revelation addresses his letters (Rev 2–3). By the middle of the first millennium the church was in the midst of controversy over the identity of Jesus Christ. Who was this Galilean miracle worker who had upended Judean society and met an untimely death at Roman hands? Was he a mere prophet? Was he a teacher? Was he God’s expected anointed one, that is, the Messiah? Was he a subordinate god to the one true God? Was he perhaps a composite figure situated between God and humanity?

The fourth-century North African priest Arius taught that Jesus was God’s creation and was not co-eternal with the Father. God is a single being, and Jesus is God’s creation with a temporal beginning to his existence. Arianism gained widespread influence in the Roman Empire, threatening not only the unity of the church but that of the empire itself.

This year marks the 1,700th anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea, summoned by the Emperor Constantine in 325 to settle the issue. While by some accounts Constantine himself was sympathetic to Arianism, he accepted the verdict of the bishops gathered on the Asian side of the Bosphorus for the sake of imperial unity: Jesus is the co-eternal Son of God, fully God and fully human. A later council, considered the Second Ecumenical Council, met at Constantinople in 381 and affirmed the divinity of the Holy Spirit, formulating what has come to be called the Nicene Creed, or the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, the most universal of the creeds of the Christian church. Together the two councils affirmed the trinitarian character of God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Subsequent councils addressed related christological issues, such as the relationship between the two natures of Christ and whether he possesses one or two wills. A seventh council decided, more controversially, that, because God had become incarnate in Christ and because Christ has a genuine human nature, he is capable of being portrayed in images—a decision that has defined the Orthodox tradition for more than 1,200 years but has been disputed by, for example, Zacharias Ursinus, the principal author of the Heidelberg Catechism (1563).

Of course, not all Christians accepted the decisions of these councils. The churches grouped together under the “Oriental Orthodox” label are dissidents from two of these. The churches in Syria and Mesopotamia dissented from the third council—of Ephesus in 431—which they believe unduly confused the two natures of Christ. They asserted that Mary was the mother of Jesus in his humanity only, rather than the Mother of God (Theotokos), as the council had decreed. The Coptic and Armenian Apostolic Churches disagreed with the fourth council, the Council of Chalcedon of 451, asserting instead that Jesus has a single divine nature. These disagreements led to the first schisms within the larger church catholic.

Ecclesiology

Second, ecclesiology. By the beginning of the second millennium of our era, eastern and western churches were drifting apart. The western Roman Empire was long gone by then, while the eastern Empire centred in Constantinople continued for another four centuries thereafter. According to the Orthodox, the church catholic consisted of five co-equal patriarchs with limited jurisdictions assigned to each. Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria together constituted a “pentarchy,” while some local churches, such as that of Cyprus, enjoyed autocephaly or self-government. However, in the western section of the church, the bishop of Rome—styled pope or pontiff—began to assert supremacy over the other bishops, including his four patriarchal colleagues. The eastern churches resisted this assertion, charging that, while the pope might be first among equals, he had no jurisdiction outside his own ecclesiastical territory. A local western addition to the Nicene Creed, asserting the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Son as well as the Father (filioque), further antagonized the eastern bishops, who had not been consulted on the issue.

Finally, in 1054 the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and the Bishop of Rome broke communion with each other. It was not the first time this had happened. An earlier break had occurred in 863, the so-called Photian schism, but this was subsequently healed four years later. Thus, it was not unreasonably assumed that the mutual anathemas of 1054 would eventually be rescinded and the unity of the church restored. Tragically, the Fourth Crusade effectively sealed the schism into permanence.

In 1204, European crusaders sacked Constantinople, temporarily ending the Roman Empire in the east and establishing in its place a Latin empire that lasted until 1261. Although the Pope, Innocent III, condemned the crusaders for their action, the damage was done, and nearly a thousand years later, eastern and western churches remain as far apart as ever. When the late Pope John Paul II visited Greece in 2001, he was largely shunned by the Greeks, who have long memories of the tragic events of eight centuries ago.

Soteriology

Third, soteriology. Although the Reformation had antecedents prior to the sixteenth century, most notably with the Lollards in England, the Hussites in Bohemia, and the Waldensians in Italy, Martin Luther is generally credited with having initiated it in 1517 by nailing his ninety-five theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. The central issue was: how are we saved? Granted, we do not save ourselves. As sinful human beings, we could not hope to accomplish our own salvation. Only Jesus Christ—true God and true man—can do this by means of his birth, life, death, resurrection, and ascension.

But might we be capable of co-operating with God’s grace in effecting that salvation? And what role do church authorities play in this? Rome asserted that she was the legitimate repository of God’s grace and that she could dispense this grace as she saw fit, citing tradition and such Scripture texts as Matthew 16:18–19. Rome also allowed that such grace could be dispensed for monetary compensation, thereby lopping off a few millennia from a purchaser’s temporal punishment in purgatory, a realm of fiery cleansing to be endured before one was allowed into heaven. There could be no assurance of salvation in this life. If one died in a state of mortal sin before a priest had the opportunity to absolve one of that sin, one’s eternal salvation was put in grave peril at the very least.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, a Dominican friar named Johann Tetzel was selling indulgences—that is, remission of temporal punishment—to fund the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. A young monk named Martin Luther was scandalized by this and, reading Paul’s letter to the Romans, came to understand that such actions made a mockery of the gospel. In reality, God’s grace is freely given to those whom he chooses, and nothing we do can possibly merit that grace. We are saved by grace through the merits of Jesus Christ, and not by the presumed merits accumulated by the saints.

Sadly, the Reformation shattered the western church nearly beyond recognition. Although there was substantial unity among the Reformers on the identity of the Bible as the Word of God and on the free nature of God’s grace, the Reformation left western Christendom divided into several major streams: the Lutherans, the non-Lutheran Reformed, the Church of England, the Anabaptists, the Socinians (unitarians), and those remaining with Rome. The Enlightenment and the various revivals further fragmented the church into thousands of denominations and, more recently, independent congregations, which became vulnerable to trends that would eviscerate the purity of the gospel.

Anthropology

This brings us to the fourth and final theme, namely, anthropology. In recent decades many churches have succumbed to the influence of trends in the larger society undermining a biblical anthropology. According to Genesis 1:26–27, God made humanity in his own image, an assertion reinforced in Genesis 5:1 and 9:6 (cf. Ps 8, as well as Sirach 17:2-4). Christian theologians have puzzled over the meaning of the divine image, some defining it as the possession of reason or some other uniquely human faculty, but it is best understood with reference to the authority God has given us over his world in response to his love.

Human beings are uniquely granted responsibility for shaping the world to meet their needs and to improve it in multifaceted ways. We take wildernesses and transform them into formal gardens. We build cities to house ourselves and to provide places for work and leisure. We create music, poetry, and novels. We craft visual arts of all kinds. We establish traditions binding in some fashion on future generations. Our descendants may follow these traditions strictly or adapt them further to suit their own changing circumstances. We organize ourselves into a multiplicity of communities, each of which has its own unique structure and task in God’s world. In short, we shape culture, and we do so in myriad ways, but always in response to God’s call.

However, the reality of our shaping of culture has tempted us to assume that we may do so in any way we please. Like our first parents in the garden, we are seduced into assuming that the world belongs to us and that we are sovereign over the course of our lives and of our civilizations. We ignore the norms God has built into his creation and act as though we are autonomous, living on our own terms and anchoring our identity in the freely choosing self. A biblical worldview affirms that our world belongs to God. The larger society, by contrast, tells us that the world, including our very selves, belongs to us and that it constitutes so much matter to be shaped according to our chosen predilections.

A century ago, a naturalistic view of science constituted the primary challenge to a biblical worldview. If the scientific method tells us that, for example, people do not rise from the dead and virgins do not bear children, then we can safely reject those parts of the Bible affirming such events as mythical and holdovers from a pre-enlightened antiquity. At the same time, so-called modernist theologians elevated religious experience to an exalted position over biblical revelation. The regnant anthropology of this era was thus a reductionist one, positioning humanity precariously between a naturalistic materialism and the free moral agency proponents were reluctant to relinquish.

These trends led to further schisms in the church of Jesus Christ. For example, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) broke with the former Presbyterian Church in the United States of America in 1936, and the following year the Bible Presbyterians broke with the OPC over eschatology, tobacco, and alcoholic beverages, among other things. Other denominations saw similar schisms take place as one after another of the major denominations was overtaken by the modernist trends.

In our century, a further shift in anthropology has occurred, but in continuity with those earlier trends. Under the influence of expressive individualism, or what I have called the choice-enhancement state, the larger culture has come to expand human autonomy to the nth degree. To be human is now seen to revolve around the capacity to choose, full stop. Our choices are our own, and no one else has the right to second-guess them. The content of these choices is now thought to be exempt from criticism from without.

The political implication of this shift is that government no longer favours some choices over others and permits an equality of expressed proclivities and even self-chosen personal identities, as long as these do not interfere with the rights of others to the same. This has given rise to a pro-choice movement whose singular issue is abortion but whose assumptions have now been extended to marriage, sexuality, and the end of life. Of course, personal choices have consequences, and bad choices have negative results for which governments will be expected to compensate. Thus, the paradox that efforts to remove government from the most intimate spheres of human activity (“There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation”) see it expanding its active presence to neutralize the effects of unwise decisions.

As they did a century ago, the major Protestant denominations have endorsed this development, often enthusiastically, adopting an ethos of indiscriminate affirmation. No longer do such churches disciple believers and call them to live according to biblical precepts; they now seek to affirm without discrimination people’s life choices under the guise of compassion and tolerance. Under such circumstances, the only sin worthy of the name is the failure sufficiently to affirm.

Some Christians argue that issues surrounding sexuality are secondary ones that can be safely put aside for the sake of unity. They may quote this well-worn adage: “In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, and in all things charity.” Unfortunately, the adage itself offers no criteria to enable us to distinguish essentials from non-essentials. However, given that Scripture affirms that “male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27) and that “the two shall become one flesh” (Matt 10:5; cf. Gen 2:24; Mark 10:8; Eph 5:31), I believe we have little choice but to conclude that our sexuality cuts to the very heart of who we are as human beings created in God’s image. Moreover, throughout the Scriptures—especially Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Hosea—we read of God likening the covenant with his people to a marriage and the people’s repeated unfaithfulness to adultery. Because of this we are now experiencing another wave of schisms as the major Protestant denominations are once more splitting over issues surrounding sexuality, resulting in the birth of the Anglican Church in North America, the Global Methodists, ECO Presbyterians, and the North American Lutheran Church, among others.

Hope for Unity?

What will be the end result of these latest church splits? Sadly, all four of these eras of church division have weakened our witness to God’s kingdom. Debates over Christology, ecclesiology, soteriology, and anthropology are not insignificant. Because each of these bears a crucial relationship to the central truths of the faith, we cannot simply ignore them or pretend that unity can be established on other grounds. Heresies remain with us and must be combatted if we are to maintain the integrity of our churches.

But there is hope. In the Old Testament we read of the tribal divisions of God’s people, especially the enduring one between Judah and the northern tribes. Even under David and Solomon, the greatest of the ancient Israelite rulers, the cleavage between Judah and Israel was barely papered over. Solomon’s levy of forced labour on the non-Judahite population severely backfired. Rather than securing the future of the Davidic dynasty, it led to Jeroboam’s rebellion against Solomon’s son Rehoboam and the permanent division of the kingdom. This fracture persisted into New Testament times in the form of the bitter animosity between Jews and Samaritans, with their competing places of worship and conflicting traditions.

But in Ezekiel we read these hopeful words:

Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I am about to take the stick of Joseph (which is in the hand of Ephraim) and the tribes of Israel associated with him; and I will join with it the stick of Judah, and make them one stick, that they may be one in my hand. When the sticks on which you write are in your hand before their eyes, then say to them, Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I will take the people of Israel from the nations among which they have gone, and will gather them from all sides, and bring them to their own land; and I will make them one nation in the land, upon the mountains of Israel; and one king shall be king over them all; and they shall be no longer two nations, and no longer divided into two kingdoms. They shall not defile themselves any more with their idols and their detestable things, or with any of their transgressions; but I will save them from all the backslidings in which they have sinned, and will cleanse them; and they shall be my people, and I will be their God (37:19–23, RSV).

There has never been a time when God’s people were unified and of one mind in all things. There has never been a time when battles have not been necessary to preserve the integrity of the gospel and the purity of Christ’s church. But by God’s grace, we can anticipate a moment when these struggles will have ended and God’s kingdom, present now in only partial form, will come to fruition. As Stone reminds us in his great hymn,

Mid toil and tribulation,

and tumult of her war,

she waits the consummation

of peace forevermore,

’til, with the vision glorious,

her longing eyes are blessed,

and the great church victorious

shall be the church at rest.

David T. Koyzis is a Global Scholar with Global Scholars Canada. He holds the Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame. He is author of Political Visions and Illusions (IVP Academic, 2019), We Answer to Another: Authority, Office, and the Image of God (Pickwick, 2014), and Citizenship Without Illusions (IVP Academic, 2024).

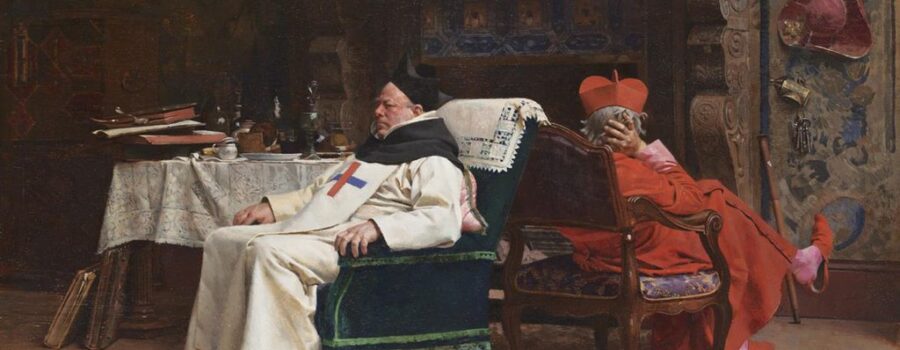

Image: Jehan Georges Vibert, The Schism