Michael J. Rhodes

Four years ago, my family joined millions of Americans in a vast array of political rituals. We watched candidates debate—and debated our friends and family in turn. I voted early and spent a few hours supporting a “get out the vote” effort. My wife helped one of our neighbors get to our neighborhood precinct on election day. We stayed up into the wee hours watching election night coverage with friends. While we waited for the results finally to be announced the Saturday after election day, we refreshed our iPhone apps constantly and kept a separate webpage open on our browsers. Political rituals dominated news headlines and our own waking hours all week.

But the most important political ritual of our election week occurred on Sunday evening, when I officiated my first baptism as an ordained pastor. Holding my beautiful niece in my arms, I poured the water on her head and joined her church family in claiming her as a child of the covenant.

Whatever else it is, baptism is a ritual of belonging. The baptismal waters offer a visible sign of a person’s ultimate allegiance. To pass through the waters of baptism is to enter that outpost of God’s kingdom known as the church. When those we baptize are babies, we perform this sacrament as a desperate plea to God to make good his promises, as a ritual welcoming our children into the visible church, and as a solemn vow to raise them to live as citizens of God’s kingdom. What could be more political than that?

Many of the political rituals that dominated our election week back in 2020 were filled with ambiguity. We prayerfully did our best to seek the good of the city to which God had sent us with our vote. And while good people who love Jesus and whom our family respects disagree with us, we celebrated that President Trump had been voted out of office. We believed his character, autocratic and anti-democratic tendencies, and many of his policies rendered him unfit for office. We were especially disturbed by the way he regularly lied about and disparaged immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.

But we also mourned. We mourned that we were deeply out of line with many of the policies of those for whom we voted. We mourned especially the failure of President Biden and Vice President Harris to defend the lives of the unborn. We mourned the deep fractures running through the body of Christ along national political lines. We mourned because we knew that many devoted followers of Jesus were genuinely as bewildered by our political choices as we were by theirs. Our American political rituals are always mixed with tears.

My niece’s baptism carried no such ambiguity. Baptism is a ritual of unrestrained joy. The God we worship is the Creator who hovered over the waters at creation, speaking all things into existence and holding them in place by the word of his power. He is the Liberator who split the waters of the Red Sea and brought his people out of the house of slavery that he might place his Name upon them. He is the Incarnate Lord who passed through the waters of baptism at the Jordan River and the Crucified and Risen King who calls his people to follow in his footsteps.

Baptismal waters run across our sacred story, catching up all God’s people in their current. When we baptize our children, we claim them for that story. We invite them to receive its promises and pledge their life-long allegiance to the only ruler worthy of their worship.

Of course, becoming a citizen of God’s kingdom in the midst of the kingdoms of our world is risky business. Jesus went straight from the water into his wilderness battle with the devil. Baptism welcomes us into a community that elicits Satan’s anger and worldly rulers’ suspicions. Small wonder that the baptismal liturgy of many traditions requires the participants to renounce Satan, the evil powers of the world, and their own sinful desires.

In the case of our children, we take the audacious step of making vows on their behalf. The church stands and pledges to raise these covenant children as part of a society that should, if all goes well, stand in constant tension with the very world in which it is called to love and serve its neighbors. We baptize them into a community whose constitution refuses—in its aspirations, at least—to organize its body politic around the ethnic, economic, national, and gender hierarchies other political powers find so irresistibly convenient.

Because there are deep wells of joy in these baptismal waters, it’s easy to forget the risk. These waters were made for drowning, after all—for dying to sin and ourselves, including those pesky status markers our individual selves so desperately desire.

On top of that, we know that the visible churches into which we welcome our children are absolute train wrecks, every last one of them. How could it be otherwise, when they’re made up exclusively of train wrecks like us? If we’re outposts of God’s kingdom, we’re outposts often in active rebellion against the desires of our divine ruler, in constant need of his intervening judgment, in order that we might not find ourselves finally condemned (1 Cor 11:32).

And then there’s the risk those we baptize pose to themselves. We claim citizenship rights on their behalf, but God knows many children who pass through these waters burn their citizenship cards later on. How dare we set this citizenship sign on our children’s heads, knowing that it must be confirmed by the kind of profession of faith that seems so seriously out-of-step with the world around us?

We dare because the Triune God invites us to dare. We dare because he has made lavish promises to his church, promises signed and sealed at the cross, promises to “us and our children and to all who are far off” (Acts 2:39). We dare because the water that trickles down our children’s heads reminds us of the blood of our King shed for the forgiveness of sins, and the holy, healing power of that same Spirit that raised our King from the dead and is at work within us. We dare because we believe that one day, his kingdom will come, and his will be done, on this very earth as it is even now in heaven. We dare because baptism is the rite of passage that welcomes us into a life of bearing witness to that coming kingdom.

I very nearly missed my niece’s baptism. I’d joyfully agreed to do it, but in the chaos of election week, it somehow slipped my mind. And that is the greatest danger of all. I don’t know all that faithfulness requires of God’s church in these strange times, but I know this: until the political affiliation poured over our heads means more than the one scribbled on our ballots, we will continue to wander in the political wilderness, susceptible to every strange wind of doctrine and every false god’s claim to be able to deliver the goods. Faithfulness requires we get our political ritual priorities right.

Four years later, it’s another election week filled with American political rituals. Once again, I find myself deeply committed to seeking the good of our nation by engaging electoral politics and am deeply concerned about the results. And once again, my most important political practice will not center on the ballot that gets counted on Tuesday, but the baptismal font where I’ll stand and baptize another niece on Sunday.

This election day, let’s remember our baptisms, even while the nations rage and we are caught up in their raging. Let’s invite our neighbors and our children into the waters, even during an election week. Let’s prayerfully imagine what our constitutional charter requires of this strange outpost of God’s empire, even as we disagree vehemently about how to live out our allegiance to God’s kingdom in the midst of this American one. Let’s worship the Risen King with lives of enemy love and neighborly justice, joyfully declaring God’s good claim over every inch of his creation.

The King has welcomed us through the waters of baptism for nothing less.

Michael J. Rhodes is the Lecturer in Old Testament at Carey Baptist College and the author of Just Discipleship: Biblical Justice in an Unjust World.

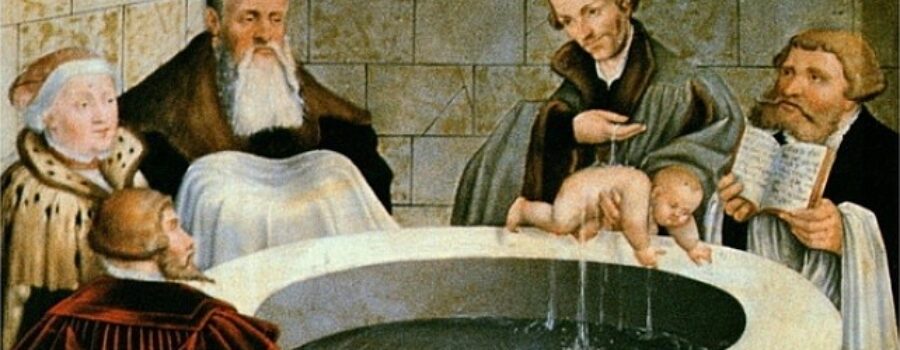

Image: Lucas Cranach the Elder, Philipp Melanchthon Performs a Baptism Assisted by Martin Luther