Hywel George

The Synoptic Gospels paint Jesus’ apostles warts and all. Their failures and slowness to learn are exposed as accents to their fledging faith, which is variously described as little, weak, or absent. The apostles are regularly cast in dim light, as those who ought to have known better. In contrast are those “minor characters” who exemplify great faith, despite disadvantages. In short, the apostles come across as genuine though “feeble, fallible followers.”1

However, John’s Gospel offers a remarkably different picture of the same people and events. The disciples are established much sooner as faithful followers who stick with Jesus through thick and thin. There is scant reference to their poor faith and more to their special training by the Lord Jesus.

This is not to suggest any contradiction at all between the Gospels. Rather, it suggests a subtle aspect of John’s agenda when writing his Gospel later than his brothers.

Internal Evidence

Glaring Omissions

Too much can be made of what John decides to leave out of his Gospel. He writes with his own purposes, so differences are to be expected.2 Nevertheless, there are trends in his Gospel that warrant investigation.

Statements about the apostles’ weak or fickle faith occur frequently and consistently in the Synoptics, but John omits them (Matt 8:26; Mark 4:40; Luke 8:25). Notably, these blemishes are sometimes dropped from narratives which otherwise well represent the Synoptics’ account, making it all the more curious. For example, John records Jesus’ walking on the water but leaves out Peter’s failure and Jesus’ admonition (Matt 14:31). Many other blunders where the apostles come across as foolish or ignorant are absent, especially where they earn the Lord’s rebuke (Matt 16:22; 19:13; Mark 8:32; 10:13–14; 14:51–52; Luke 18:15).

Around Jesus’ passion, we know “they all forsook him and fled” (Matt 26:56; Mark 14:50), but John leaves this out. In its place he makes unique inclusions, highlighted below. Around Jesus’ resurrection, the apostles are backgrounded in the Synoptics. They are silhouetted as those dominated by doubt and fear, compared with those shining women who believed. One can hardly miss the stark relief in which they are held. Also, if the long ending of Mark’s Gospel can be taken as a late addition, it could be understood as representing the overall Synoptic opinion of the apostles after the resurrection. The assessment finds them doubting, unbelieving, and scathed by Jesus’ rebuke “for their lack of faith and their stubborn refusal to believe those who had seen him” (16:11, 13, 14).3 However, John passes over all of this entirely, making no reference to faithless fear, doubt, or unbelief at all (cf. Matt 28:17; Mark 16:11–14; Luke 24:11, 37–38).4

Unique Inclusions

In the Synoptics, the disciples are listed later on into Jesus’ ministry, and before they confess him as Christ (Matt 10:2–4; Mark 3:14–19; Luke 6:14–16). John includes different data. The apostles are said to believe on Jesus early (2:11) and identify him as Christ and Son of God from the beginning (1:41, 49). These things occur even before Jesus’ ministry begins in earnest and before the events of Caesarea Philippi.

When Jesus’ ministry does begin, even at this early juncture, John reveals that Jesus’ disciples are those who are baptising penitents on behalf of Jesus himself (3:22 cf. 4:2).

The unique discourse in John 6 provides occasion for John to point out that, while many disciples fell away offended, the apostles remained faithful to Jesus, though his teaching was hard (6:66–69). Their loyalty to him is clarified by their readiness to die with and for him (11:16; 13:37). On 11:16, Carson observes that so-called “doubting” Thomas reflected “not doubt but raw devotion and courage.”5

In John, copious attention is given to the private ministry of Jesus which he devotes to the apostles, especially chs. 13–17. This includes special preparation and equipping for ongoing ministries. Within this material, several sections are especially pertinent. John presents the apostles as those with a special relation to Jesus’ teaching and his Holy Spirit (14:26; 16:13–15) which grants them unique authority (20:22–23). They are peculiarly appointed as Jesus’ friends to bear fruit for him (15:15–16). In Jesus’ prayer (ch. 17), he sets apart the disciples as special men who believe, receive, and preach the words of God about Jesus. There are only a few characters in the prayer, and the human characters besides Judas are of only two categories: the apostles and those who will believe in Jesus through their word.

Although in the synoptics, “all fled,” John’s presence is noted at Jesus’ crucifixion (19:25).6 After Jesus’ resurrection, John completely passes over any faithlessness in the apostles. Instead, he includes their irrepressible eagerness and joy (20:2–8, 20). Upon reaching the empty tomb in 20:3–8, John and Peter see what is there. Three different verbs for “to see” are used in swift succession, suggesting that they are realizing the significance of what had happened—they “saw and believed.”7

Before Jesus ascends, John lavishes space on apostolic encounters with the risen Lord. He spotlights again their preparation for ongoing ministry in the Church (20:30). All this being so, one wonders: Why does John include Peter’s denial (18:15–27)? Perhaps for the sake of establishing Peter’s dazzling restoration by Jesus himself, which includes Peter’s particular commission to shepherd Jesus’ flock, the church (21:15–17).

The stumblings of the apostles which John chooses to include are more benign than in the Synoptics. Compare the exasperated rebukes of the Synoptics with the mild encouragements of John’s Gospel (Matt 15:16; 16:8 cf. John 4:31–34; 11:12–15; 13:8; 14:8–9).

External Circumstances

Most understand that John’s Gospel was written later than most of the epistles.8 In the intervening time, the apostles had come under scrutiny and met opposition within the church. There were false teachers and bold individuals willing to speak in competition with and opposition to the apostles. Many refused to submit to their authority and accept their doctrine (Gal 1:6–9; 1 Tim 1; 4; 6:20–21; 2 Tim 1:15; 3; Jude 4). A special mention goes to infamous Alexander who resisted “our words” (2 Tim 4:14).

In several places, the epistles include the occasional tone of self-defence and reluctant self-attestation—particularly in Corinthians, but elsewhere too (Gal 1:11–2:1; 6:17; Eph 2:20; 3:5; 2 Thess 3:9; 2 Pet 3:2; Jude 17). John seems personally aware of this difficulty when writing (1 John 1:1–4; 2 John 7–11). This was doubtless a sensitive thing for them to tackle as servants marked by humility and willing to become nothing for Jesus’ sake (1 Thess 2:6).

Since this ecclesiastical friction constitutes part of the environment in which John wrote his Gospel, it may go some way toward explaining the different way in which John paints the apostles. Part of John’s agenda in writing the Gospel was certainly to clear up errors and rumors in the churches, exemplified by 21:20–35.9 This objective may have extended to the correction of the broader intolerable attitude in corners of the church which was begrudging of the apostles.

Conclusion

The Synoptic Gospels depict the disciples in a more historiographical mode: they grow in understanding and faith in Jesus; they are graciously helped along a faltering journey; then they are specially commissioned to service in the church. This is certainly the truth. However, John’s Gospel deliberately casts them as more potent characters. They are reliable, faithful followers of Jesus, especially chosen and trained to carry his authoritative teaching in the church. This may have been a considered corrective move by John in order to address pressing issues of authority in the fledgling Christian community.

If this is true, then part of John’s objective is that Christians should think rightly of the apostles. While they are mere men, sinners saved by grace, they are also the mouths through which the world has heard the good news of Jesus (17:20). Christians ought highly esteem and heed the apostles as ambassadors of Christ. We are to receive and pass on their doctrine (2 Tim 2:2).10

Postscript

Other features of John’s Gospel admittedly may pose a problem for the above observation. In this author’s estimation, they are outweighed but warrant further examination. Included in John’s Gospel are Peter’s denial, Peter’s strike against Malchus, and James and John’s angling for thrones. Strangely omitted is Peter’s weeping contrition and the designation of Peter as “the rock.”

Hywel George is a pastor in Maesycwmmer, Wales, United Kingdom and a graduate from Union School of Theology. You can follow him on Twitter @_HywelGeorge.

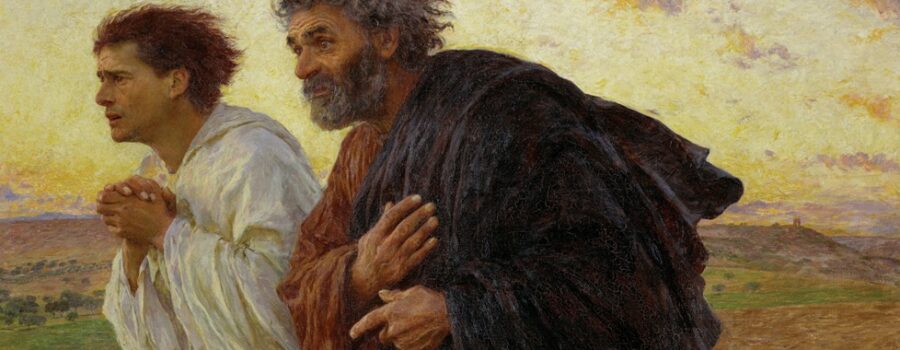

Image: Eugène Burnand, The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning of the Resurrection

- Cornelis Bennema, Character Analysis and Mircale Stories in the Gospel of Mark (WUNT 339; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), 413–26.[↩]

- Donald A. Carson, The Gospel According to John (Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1991), 49–58. Donald A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Leicester: Apollos, 1992), 160–66.[↩]

- Carson, Moo, and Morris, Introduction, 102–4.[↩]

- John 20:19 refers to fear, but given the circumstances, it is probably legitimate and not necessarily faithless. The scene of Thomas’ doubt is unique to John’s Gospel but only occasions a tremendous profession of faith that Jesus is Lord and God.[↩]

- Carson, John, 410.[↩]

- For the identity of the beloved disciple see Carson, John, 472–73.[↩]

- The three verbs are βλέπω (v. 5), θεωρέω (v. 6), ὁράω (v. 8).[↩]

- Carson, John, 82–87. Carson, Moo and Morris, Introduction, 166–68.[↩]

- Carson, John, 681–83.[↩]

- For a good examination of the apostles’ doctrine as it is in oral tradition, see David Wenham, From Good News to Gospels: What Did the First Christians Say About Jesus? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 36–64.[↩]