David Koyzis

When I was 21 years old, I had an opportunity to visit what was then called Czechoslovakia, still in the iron grip of a Communist Party ruling unopposed since 1948. As a member of the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact, it had borne the brunt of the interventionist Brezhnev Doctrine eight years earlier, with Soviet and allied military troops crushing Alexander Dubček’s liberalizing Prague Spring.

During our stay soldiers appeared everywhere in the streets of the capital city, and our student group had the uneasy feeling of being in an occupied country. However, we had an even more vivid sense that ordinary Czechs had long ago ceased to believe in the fictions being disseminated by the regime. Two episodes in particular gave me an insight into the true sentiments of the people.

First, our group of university undergraduates was given an opportunity to speak with a representative of the country’s foreign ministry. He presented to us his department’s official stance, which was to maintain a defensive posture against a possible West German invasion. Remarkably, our group was permitted to ask questions afterwards. A young man posed the obvious query, which in some fashion was likely on all of our minds: Why worry about Germany when the last country to invade was Russia? We perked up our ears for the response, wondering whether we’d hear the truth or something else.

Our host was very gracious. He paused for a moment and sighed. Then he spoke, choosing his words carefully. We had to understand, he said, his own position at the foreign ministry, where he was limited to implementing policy and had no authority to make it. Or something along those lines—I no longer recall the exact phrasing. Perhaps he was a typical bureaucrat, such as we might find working in any government department anywhere. Yet I came away with the distinct impression that he was telling us a story he himself did not find altogether credible.

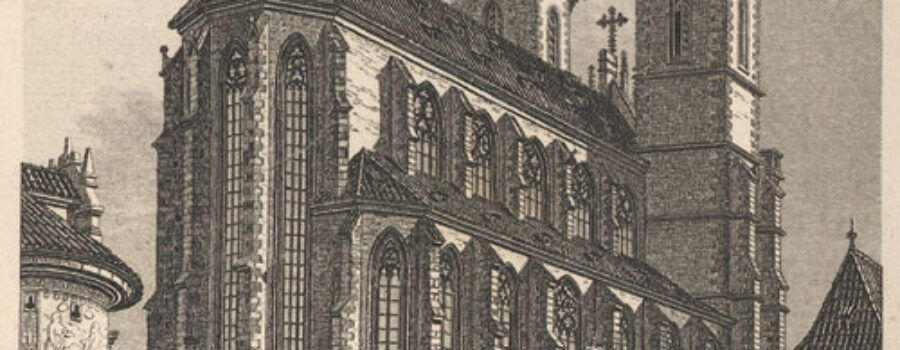

Second, while standing in the Old Town Square about 400 metres east of the Vltava River, I was admiring an old church building—the Church of the Mother of God Before Týn, a 14th-century edifice controlled for 200 years by the proto-protestant Hussites.1 As it appeared to be surrounded on all sides by smaller buildings, I tried in vain to find an entrance. As I was obviously a foreigner and looking somewhat lost, a quite friendly man came up and started talking to me in German, a language still familiar to older people who had grown up during the Habsburg era. With my dark hair and eyes I couldn’t imagine why he would think I was German, but German tourists from both east and west were probably the most common visitors at the time. We quickly switched to English, and he offered to buy any foreign currency I might have for twice the official exchange rate, something that was technically illegal but to which the authorities seemed to turn a blind eye. Being young and moderately daring, I readily offered him my US dollars and Swiss francs in exchange for more korunas than I could manage to spend in the remaining days of our visit.

I asked how to get into the church, but rather than giving me verbal directions, he offered to accompany me personally inside. As no worship services were being conducted, people were milling about, admiring the gothic interior. On his own initiative he began to talk politics, which surprised and unnerved me. Quite openly, he told me that one day they would kick out Leonid Brezhnev and the Russians and bring back Dubček. He made no effort to whisper, his voice echoing faintly inside the sanctuary.

Despite this seditious talk, the other visitors paid no attention. I glanced about nervously, expecting at any moment to draw the attention of the police. But nothing happened. That’s when it occurred to me: no one actually believed the official ideology anymore. People were keeping their heads low, living reluctantly within the redemptive narrative told by a “liberating” ideology, anticipating the day when the regime would be gone. When the end did come thirteen years later, I was not as surprised as many others that it happened so quickly.

I recalled my youthful visit to Czechoslovakia while reading Rod Dreher’s new book, Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents (Sentinel, 2020). A sequel to his 2017 book, The Benedict Option, it explores past trends that forced Christians to congregate into small groups to preserve their faith in the midst of state-imposed atheism. Dreher believes that the stories he was told by those who lived through communist tyranny have relevance for us, who are in danger of being lulled into a “soft totalitarianism” in which mass incarceration and state-sponsored murder are replaced by the subtle pressure of social and economic ostracism by elites in the grip of an ostensibly progressive agenda. This book lays out in stark terms the conditions that make the formation and nurturing of such small communities necessary.

I found compelling the testimonies of those who survived Marxism-Leninism and provided aid and comfort to dissidents and victims of the regime. Dreher dedicates the book to one of these: Father Tomislav Kolaković (1906–1990), a Jesuit priest born and raised in Croatia who relocated to Slovakia during the Second World War. Kolaković’s principal contribution was to energize communities of faithful Christians through the Nazi and communist occupations of central Europe. The network of Catholic communities he inspired, known as the Family, suffered persecution following the communist takeover of Czechoslovakia, later emerging to become the nucleus of an underground church paving the way for the Velvet Revolution. While the institutional church in Slovakia and elsewhere succumbed to the pressures of the regime and thereby compromised the gospel message, the underground churches, because they were based on small intentional communities imbued with the principles that Kolaković and others taught, were able to endure at a certain distance from the official ideology.

Drawing on Hannah Arendt (The Origins of Totalitarianism), Philip Rieff (The Triumph of the Therapeutic), Czesław Miłosz (The Captive Mind), Robert Putnam (Bowling Alone), and others, Dreher offers a daunting vision of modernity and postmodernity, in which a contemporary West, pulled from its deep spiritual roots, is following an agenda hostile to historic Christianity. This agenda revolves largely around a “Myth of Progress…which has for generations defined progress as the liberation of human desire from limits” (67). The Sexual Revolution is a large part of this, but so are consumerism, “woke capitalism” (chapter 4), “surveillance capitalism,” and identity politics.

In my own Political Visions and Illusions, I have described the “choice-enhancement state” as the latest stage in the centuries-long development of liberalism, in which the quest to expand the range of choices available to the individual has enlarged the scope of state action beyond the narrow limits envisioned by such early liberals as John Locke and Adam Smith. Under such a regime, oppression is so broadly defined as to render intolerable any standard that diminishes the number of options for the sake of encouraging virtue and discouraging vice. A government in the grip of this ideological vision will thus come to regard churches and faith-based organizations as problematic at best. Dreher understands this dynamic better than many of his fellow Christians.

Given these developments, Dreher attempts to answer the question, “Can It Happen Here?” (89). In other words, can the totalitarianism that reigned across a wide swath of the Eurasian continent during the twentieth century recur in the west, including North America? Based on his conversations with survivors of Nazism and communism, Dreher believes it can. Furthermore, it is most likely to come on the tails of a collection of agendas styled progressive. Yet the “Right” is scarcely exempt from Dreher’s criticism:

Relativism clad in free-market dogma aided the absorption of the therapeutic ethos by the Religious Right. After all, if true freedom is defined as freedom of choice, as opposed to the classical concept of choosing virtue, then the door is wide open to reforming religion along therapeutic lines centered around subjective experience.2

Even conservative churches have succumbed to a therapeutic spirit in which suffering becomes inconceivable and “bearing pain for the sake of truth seems ridiculous” (13). We may not have arrived at this gloomy future yet, but we need to be prepared for the possibility. How? Primarily by forming and maintaining the sorts of communities Dreher extols in his earlier Benedict Option. These will help us to nurture the faith and to defend truth until a more favourable moment arrives.

Is Dreher correct in his forecast? One reviewer has observed that Dreher appears motivated by fear and lacks any sense of joy or hope. Another accuses him of reviving the heated rhetoric of the Cold War. Yet having grown up living across the street from a man who had been a prisoner in the Soviet gulag for ten years after the Second World War,3 I can easily comprehend how such personal trauma heightens one’s alertness to trends that might replicate such conditions at home. Thus, we ought not be surprised at the apprehensions survivors would express to Dreher over the direction taken by their post-communist or adopted homelands. Could too expansive a nondiscrimination regime produce a climate in which faith-based communities, with their distinctive standards for membership, will be suppressed? Could a therapeutic focus on the expressive individual create an inhospitable climate for churches which by their very nature call members to subordinate their own wills to God’s word? We would be unwise to deny such possibilities.

Having studied and written about political ideologies for decades, I believe that all ideologies have totalitarian potential. They may not lead to forced labour camps or mass murders, but they do make claims which compete on a basic level with the traditional religious faiths, and they do require sacrificial victims, if only in damaged reputations and fewer career opportunities. This is why we need above all to be spiritually discerning in our assessment of them.

Yet, political ideologies do not operate in a contextual vacuum. All of us, whatever our ultimate convictions, live and work within the larger panorama of God’s creation. Even if a Supreme Court justice proclaims that “[a]t the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life” (Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 1992), the cosmos itself remains stubbornly unpersuaded, impervious to our subjective notions of its meaning or lack thereof.

The Dutch statesman and polymath Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920) alerted us to the reality of God’s common grace,4 which encapsulates the biblical dictum that “he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matt 5:45 RSV). Even if we fail to acknowledge the Giver, we nevertheless receive his gifts, availing ourselves of the fertility of the soil, electrical energy, shelter from the elements, nourishing meals, and so much more. Our shared cultural project is a genuine blessing of God, as we, who are created in his image, continue to live and work out what is often called the cultural mandate (Gen 1:26–28). A common world makes it possible for believers in different faiths and ideological visions to communicate and co-operate with each other within the same institutions and communities. I doubt that Dreher would openly disagree with any of this, but if he were to make more of God’s common grace, he might be more hopeful in his assessment of our shared human future.

Indeed, even beyond God’s common grace, there is reason for hope, especially if we expand our horizons to cover a shrinking globe, made even smaller by the online communication platforms that have blossomed during the COVID pandemic. In recent years I have reoriented my own academic ministry beyond North America, with special attention to Brazil, where my first book was published in Portuguese translation in 2014. In 1980 there were 120 million people in that country, of whom about 6 percent might be considered evangelicals. Thirty years later Brazil had a population of 195 million, with evangelicals amounting to 22 percent. This year Brazil’s population is estimated to stand at nearly 213 million, and as of seven years ago the evangelical population was thought to have reached 28 percent. Yet, even with this explosive growth of evangelicalism, Brazil remains the largest Roman Catholic country in the world.

Brazil is not alone. Philip Jenkins’ writings have demonstrated that the global centre of Christianity has moved from its traditional geographic locations in Europe and North America to sub-Saharan Africa, east Asia, and Latin America. If Christians are being persecuted at levels unseen in centuries, it is not because of a secular conspiracy to finish off a dying religion. Quite the opposite: the church is growing quickly around the world, and many tyrannical regimes, most notably that in Beijing, feel threatened by the gospel’s steady advance.

Dreher’s book is timely, and his warnings need to be heard. Regrettably, there is always a place for contemporary Jeremiahs, following the ancient prophet, to speak to those who have become complacent and too comfortable with the mores of the larger culture. We ought not to dismiss Dreher’s concerns just because we prefer to hear something less negative or because he doesn’t address other issues worthy of concern. At the same time, we have ample cause to hope, given that our faith is in Jesus Christ, whose kingdom will have no end.

So, yes, we must continue to nurture our Christian churches and day schools, our Christian universities and publishing houses, our home Bible study groups, and so forth. But we should do so in the spirit not of circling the wagons but of joining hands with our fellow believers around the world and, with them, living out the biblical command to love God and our neighbour in the present age. The future belongs to Jesus Christ, and we can take heart that the negative trends to which Dreher rightly alerts us constitute only a temporary setback in the progress of his kingdom.

David T. Koyzis is a Global Scholar with Global Scholars Canada. He holds the Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame. He is author of Political Visions and Illusions (IVP Academic, 2019) and We Answer to Another: Authority, Office, and the Image of God (Pickwick, 2014).

Image: Our Lady of Tyn, from J. E. Födisch, Gemälde von Prag und dessen Umgebungen (1869)

- See https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hussite.[↩]

- Dreher, Live Not by Lies, 13.[↩]

- See https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23132216/john-h.-noble.[↩]

- See https://abrahamkuyper.com/.[↩]