David T. Koyzis

In the book of Exodus we read that God’s people were slaves in Egypt for centuries before Moses led them across the Sinai Peninsula to Canaan, liberating them from their oppressive overlords and giving them a new life in a new land. Since then, the category of oppression has played a significant role for Jews and Christians alike.

God created human beings in his own image, and all persons share this image equally, irrespective of sex, race, nationality, and intelligence. This is the great truth that motivated nineteenth-century abolitionists to combat the institution of slavery that held the American South in its grip. How could a Christian possibly treat another human being as a piece of property to be exploited for his labour without adequate compensation, to be bought and sold and separated from spouse and family, to be treated as subhuman? Not all historical examples of slavery were based on racial differences, but in the New World slavery certainly had a racial character.

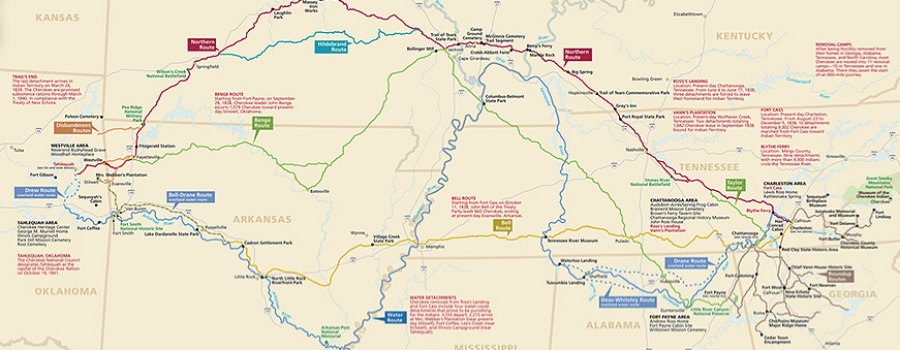

To make matters worse, Europeans in North America displaced the aboriginal populations, moving them westwards to free up their lands for settlement and cultivation, pushing them onto reserves constituting a small portion of the lands they had once occupied. Old World diseases wiped out many of the aboriginal peoples, but those who survived were treated as trespassers on their own territories. The Trail of Tears, in which the southeastern tribes were sent to Oklahoma between 1830 and 1850, is a stain on the American historical record. So widespread were such examples of oppression that some people are inclined to view the entirety of American history as tainted by the reality of white oppression of nonwhite peoples.

The details of history, however, sometimes resist the simple stories we tell. In 2018 Smithsonian Magazine published an article that upends the usual tales of oppression: How Native American Slaveholders Complicate the Trail of Tears Narrative. Prior to their deportation, the Five Civilized Tribes—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—inhabited the American southeast, living in much the same way as their European neighbours. This similarity included that “peculiar institution” of slavery. On his thousands of acres along the Mississippi River, Choctaw Chief Greenwood LeFlore kept 400 black slaves. Even John Ross, Chief of the Cherokee, who unsuccessfully campaigned against the Indian Removal Act of 1830, was himself a slave-owner and defended slavery.

Paul Chaat Smith, a Comanche and curator of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, expresses what many people might have expected to hear:

“Obviously,” Smith said, “the story should be, needs to be, that the enslaved black people and soon-to-be-exiled red people would join forces and defeat their oppressor.” But such was not the case—far from it. “The Five Civilized Tribes were deeply committed to slavery, established their own racialized black codes, immediately reestablished slavery when they arrived in Indian territory, rebuilt their nations with slave labor, crushed slave rebellions, and enthusiastically sided with the Confederacy in the Civil War.”1

Since at least the French Revolution, tales of slave revolts and other rebellions against oppressors have acquired a certain romantic glow. Spartacus’ revolt against the Romans in 73–71 BC is remembered by some as a proto-Marxist proletarian revolution. Marx himself was an admirer of Spartacus, whose legacy inspired, among others, film director Stanley Kubrick and Soviet Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian. Even Moses has been treated as a great liberator by Cecil B. DeMille, who made two cinematic versions of the biblical story, and by the directors of the 1998 animated musical The Prince of Egypt.

So what gives? How can one group of people who have suffered oppression go on to oppress others? Why didn’t the Five Civilized Tribes conspire with African-American slaves to unseat their white overlords and establish a more egalitarian society?

Some academics have come up with a theory of intersectionality to account for this phenomenon. This changes the larger narrative to some degree, as now the lines separating oppressors and oppressed intersect, putting some people in more than one category, thereby creating a hierarchy of oppression. If you are a European-descended heterosexual woman, you may be oppressed as a woman but are in an oppressing class as a white and as a heterosexual. If you are nonwhite and a lesbian, you find yourself triply disadvantaged within the larger societal system of oppression. In the case of the southeastern aboriginal peoples, their leaders had absorbed the values and ways of their southern white neighbours, aping their oppressive practices, and joining with them in keeping black slaves.

While intersectionality introduces an element of complexity into the simple story of oppression as told especially by Marx and his followers, I would suggest that the biblical redemptive narrative better accounts for slave-holding aboriginals in so far as it recognizes that oppression is but one manifestation of the reality of sin. In light of this, we need to be aware of two factors that complicate the usual stories told about oppressors and oppressed.

First, we need to clarify what it means to be oppressed. Because of our sinful nature, we often claim to be oppressed when we simply dislike having to live under standards and norms that conflict with our desires. In a culture that celebrates individual self-seeking and the freedom to “march to a different drummer” nearly for their own sake, there is a tendency to try to diminish ties of obligation that cannot be reduced to our free wills. As such, a child might conceivably claim to be oppressed when her mother asks her to come in from outside and make her bed. Or we may think ourselves oppressed when compelled to pay taxes, to submit to certain government regulations, or to accept limitations on the use of our property. While governments sometimes go to excess in all three areas, we need to be careful not to group such excesses together with outright slavery and the persecution of minority groups and political opponents.

Second, after we have come to a clearer understanding of oppression’s meaning, we should still be wary of grouping people into fixed categories. This way of thinking definitely has Marxian origins. Marx divided humanity into two classes defined by their relation to the means of production. In the mature capitalist stage of history, the capitalist class, or the bourgeoisie, faced off against the continually expanding industrial working class, or the proletariat. Because the bourgeoisie monopolized power over society, exploiting their superior position for their own benefit, the proletariat would suffer at their hands until they were numerous enough to overcome their oppressors, expropriate the means of production, and distribute them to everyone equally. The classless society that would supposedly ensue was attractive enough to command the loyalties of millions in the century following Marx’s death.

Marx’s expectations were not, of course, borne out by subsequent history. But his ideas live on in contemporary notions of oppression that categorize people according to their status as oppressors and oppressed, even if economic class is no longer the major criterion.

In the real world, as we relate to each other on a daily basis, we will quickly discover that the title oppressor cannot be easily assigned to a particular group of people, primarily because this status will not hold still. As soon as we think we have identified and labelled the oppressors, something happens to upend our conclusions. Those victimized in the past turn right around and victimize others. Once the party claiming to represent the working class has overturned its capitalist overlords, it begins to persecute dissidents and those it deems to be obstructing the new order’s arrival, irrespective of what they have actually done. In their efforts to build a better world, revolutionaries typically end up turning on their own followers, creating a society more oppressive than the one they overturned. This is true of the Soviet Union, whose founders replaced a decadent and corrupt tsarist regime with one that would murder tens of millions of people over the following years.

Yes, there are oppressors and victims of oppression. No one can doubt that mandatory racial segregation oppressed African Americans for generations. Even now the government of China is persecuting Muslim Turkic-speaking Uyghurs in its western Xinjiang province. Beijing is also closing churches and arresting pastors, such as the Rev. Wang Yi of the Early Rain Covenant Church in Chengdu. It is not difficult to locate examples of oppression, and we are right to work and pray to correct these evils as part of the biblical mandate to do justice.

However, as Bishop Lesslie Newbigin has correctly observed, “while oppression and injustice are undoubtedly an important part of the human scene, most people are in an ambivalent position, oppressors in some situations and oppressed in others.”2 Indeed, as soon as we begin to see ourselves as victims, we easily become blind to our capacity to victimize others. I saw this dynamic at work during a visit to Israel and the Occupied Territories twenty-five years ago, as each side persistently declined to take responsibility for the miseries it had inflicted on the other, its victim status somehow giving it the moral high ground irrespective of its members’ actions.

The biblical redemptive story offers a truer analysis of the human condition than a Marxist or quasi-Marxist reading could ever do. Even intersectionality falls short as an explanation for the Five Civilized Tribes’ enthusiasm for slavery. Here’s Newbigin again: “Before the cross of Jesus there are no innocent parties. His cross is not for some and against others. It is the place where all are guilty and all are forgiven. The cross cannot be converted into the banner for a fight of some against others.”3

It is not simply that aboriginals were aping their European neighbours. Like all people, they were subject to sin, which worked itself out in how they lived their lives and organized their communities. A recognition of the universality of sin and the need for forgiveness could help to heal divisions and to bring reconciliation in the midst of an increasingly polarized society. Only then are we likely to stop pointing the finger at others and look into our own hearts, seeking forgiveness for our sins of omission and commission, as well as extending forgiveness to others.

David T. Koyzis is a Global Scholar with Global Scholars Canada. He holds the Ph.D. in Government and International Studies from the University of Notre Dame. He is author of Political Visions and Illusions (IVP Academic, 2019) and We Answer to Another: Authority, Office, and the Image of God (Pickwick, 2014).

Image: Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Map, National Park Service

- Ryan P. Smith, “How Native American Slaveholders Complicate the Trail of Tears Narrative,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 6, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-native-american-slaveholders-complicate-trail-tears-narrative-180968339/.[↩]

- Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel and a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids and Geneva: Eerdmans and WCC Publications, 1989), 150.[↩]

- Ibid., 151.[↩]