Joshua Coutts

Generations of Bible interpreters have wrestled with the question of how to read Scripture. In a postmodern era, we are as aware as ever of the impact our pre-understandings have on how we interpret the world, our experience, or even the Bible. At the same time, we retain a desire for some authority outside ourselves by which to set our course. And we are drawn to techniques and methods that provide some measure of confidence and control in the process of interpretation.

Interestingly, however, we find a strikingly similar set of concerns reflected in the Gospels, where Jesus is regularly engaged in conflict with opponents over how to read and approach Scripture. John’s Gospel in particular sheds light on this issue in ways that are as relevant as ever: John upholds the authority of Scripture and the importance of careful interpretation. Yet, at the same time, he alerts his readers to the limitations of exegetical technique alone.

Scriptural Conflict in John

In John’s Gospel, Jesus’s opponents are characterized as interpreters of Scripture—even expert exegetes. In John 7, they mock followers of Jesus as those who do “not know the law” (7:49). Likewise, they rebuke the blind man for presuming to “teach” them (9:34), for they are true “disciples of Moses” (9:28–29). And somewhat pejoratively, they tell Nicodemus that if he carefully interprets, or “searches,” the Scriptures, he will come to agree with their assessment of Jesus (7:52).1

Indeed, as those who keep the law and study Scripture, they are ideally positioned to oppose Jesus on the basis of Scripture. So, they point out that his Galilean provenance disqualifies him as “the prophet” (7:52), and his Sabbath-breaking (5:10, 16; 7:23; 9:16) demonstrates that he is “not from God” (9:16). Indeed, they likely regarded Jesus as the false prophet warned against in Deuteronomy 13:1–5, who would perform signs and lead Israel into apostasy (cf. 11:47–48).2 Consequently, they have him arrested and commend him to Pilate as worthy of death in accordance with their law (19:7). In these passages, opposition to Jesus is based consistently on scriptural grounds.

In preserving this material, John seems remarkably to have conceded scriptural territory to Jesus’ opponents. Jesus himself makes this concession when he declares to his opponents, “you search (i.e., exegete) the scriptures” (5:39). Yet, at the same time, Jesus indicates there is something fundamentally off in their approach to Scripture when he follows this up with “because you think that in them you have eternal life.” John hints, likewise, that exegetically based discussion alone is no guarantee of access to the truth when he reports that the Jews, who were all agreed on the authority of Scripture, were “divided” among themselves over Jesus (7:43; cf. 6:52; 10:19).

This is not to say that there is no place for exegetically based debate. Jesus regards Scripture as authoritative and appeals to it in his own defense: “Is it not written in your law, ‘I said, you are gods’? . . . and the Scripture cannot be annulled” (10:35). Likewise, he accuses his opponents of failing to keep the law (7:19). Moreover, he engages in exegetical techniques of the time in his self-defense, such as a “how much more” (qal wahomer) style argument in 7:23: “If a man receives circumcision on the sabbath in order that the law of Moses may not be broken, are you angry with me because I healed a man’s whole body on the sabbath?” (7:23).3

He also corrects the exegesis of his interlocutors, as for instance, in his response to the crowd’s scripturally based expectation that Jesus might produce bread from heaven: “It was not Moses who gave you the bread from heaven, but it is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven” (6:32).4 John himself, of course, shares Jesus’ perspective about Scripture as a non-negotiable authority and employs exegetical techniques used by Jewish interpreters more widely in his own interpretation of Scripture, such as linking different Old Testament passages via shared “catchwords” (e.g., Isa 6 and Isa 53 in Jn 12:38–40).

A Believing Posture

So far, all “sides” in John’s Gospel are agreed, and it would seem that Jesus and his interlocutors could simply “agree to disagree” over their interpretations of Scripture. But it is precisely at this point that John’s Gospel introduces an additional and crucial hermeneutical question: what is your posture toward Scripture and toward Jesus himself?

It is suggestive that Jesus does not engage Nicodemus as a fellow “Teacher of Israel” in an exegetical discussion but rather invites him to be born from above.5 If there is a hermeneutical issue implicit here, it is clarified in the conflict of John 5: Jesus acknowledges that the Jews “search” the Scriptures, but only after first charging that they have “never heard [God’s] voice . . . and do not have his word abiding in [them]” (5:37–38). The distinction between “searching Scripture” and “hearing the voice of God” indicates that biblical interpretation itself does not guarantee an encounter with the “word” of God. It is fitting, then, that Jesus concludes not with an invitation to read or understand Moses aright but rather to believe him: “If you believed Moses, you would believe me” (5:46).

Similarly, the crowd in 12:34 is exegetically correct to expect the Messiah to “remain forever” (John himself concurs that Jesus indeed abides forever with his followers through the agency of the Paraclete in 14:16–18). However, it is their failure to believe in him, John tells us (12:37), that leaves them blind to his true identity. Likewise, before the resurrection, the disciples did not yet “understand” the Scripture (20:9). Yet, afterward, they “believed the Scripture” (2:22). The shift from “understanding” to “believing” language is not simply charting a cognitive continuum from misunderstanding to comprehension. Rather, these passages mark a shift from the discourse of Scripture-searching or exegesis to the discourse of believing, a shift that is commensurate with John’s characterization of followers of Jesus, not primarily as “disciples” (over against the “disciples of Moses” in 9:28), but as believers.6

Consequently, John’s primary response to law-based accusations against Jesus is not to establish Jesus’s innocence vis-à-vis Scripture as such. Rather, John reframes debate in terms of Jesus’s own identity. So, in John 5, the charge of Sabbath-breaking is reframed as an issue of Jesus’s relationship to the Father. Similarly, although the dialogue of John 6:30–31 appears to feature Jesus correcting the exegesis of his Jewish interlocutors, this correction is prefaced by and grounded in the emphatic formula “Truly, truly, I tell you” (6:32), and followed by the Bread Discourse in which Jesus himself is elevated over the manna of the wilderness generation, as well as (more implicitly) over Moses and the law. It is fitting that John’s Gospel features as much, if not more, conflict among the Jews over Jesus (6:52; 7:43; 10:19) as between Jesus and his opponents over Scripture. For John, the crucial locus of debate is not Scripture and its interpretation, but the posture of the heart toward Scripture, and even more fundamentally, toward Jesus.

Faithful Reading

This is not to say that Scripture, properly understood, is actually displaced. That would set up an opposition between Scripture and Jesus against which John’s whole Gospel is levied. In John, Jesus pushes his interlocutors to interpret Scripture more faithfully, and it remains axiomatic that we encounter Jesus and grow in faith precisely in the context of reading and interpreting Scripture. Indeed, John’s Gospel itself, as part of the canon of Scripture, enables us to see and understand Jesus aright. Modern biblical exegesis has generated much that is fruitful and helpful and provides invaluable counter-measures against our tendency to read our own ideas and desires into Scripture.

However, John also registers a certain realism regarding the limits of human effort to rightly interpret Scripture. Truth is heard and understood not through exegetical technique alone, but through reading Scripture with a believing posture. Thus, John is also teaching us here how to read Scripture aright.

Through the characterization of Jesus’s opponents in the Gospel, John warns us that scriptural interpretation that is conducted in isolation from believing is dangerous. It deludes us into thinking that “searching the Scriptures” guarantees access to the truth, to right understanding. And so, ironically, “searching” or interpreting Scripture can inoculate us from the “word of God” (5:39).

John was not naïve. He was all too familiar with the reality of varying, even opposing, interpretations of Scripture and understood that they cannot all be equally valid. Long before Augustine and Anselm, he emphasized that believing aright necessarily facilitates reading and understanding aright.7 And he underscores that hermeneutics is inseparable from Christology. As Scripture fundamentally discloses the heart of God to us, our full apprehension of that revelation requires our participation. Therefore, rather than “think up” to the right understanding of Scripture, John invites us to “lean in” to it, just as the Beloved Disciple leaned in to the breast of the incarnate Word, who alone truly exegetes the Father (13:25; 1:18).8

Joshua Coutts completed his Ph.D. at the University of Edinburgh and serves as Assistant Professor of New Testament at Providence Theological Seminary, Otterburne, Manitoba. He is the author of The Divine Name in the Gospel of John: Significance and Impetus (Mohr Siebeck, 2017).

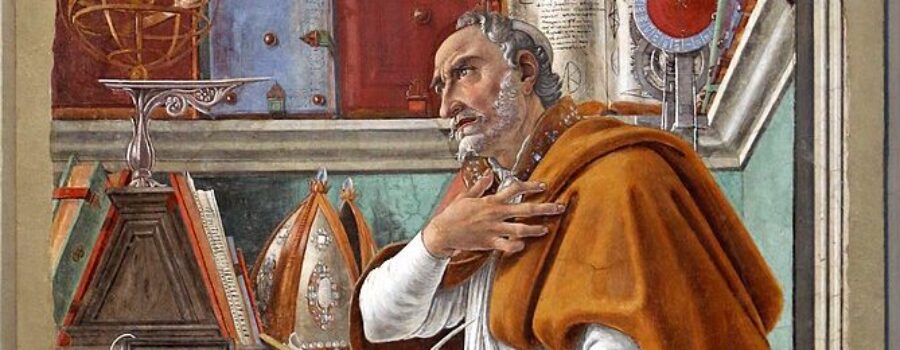

Image: Sandro Botticelli, Saint Augustine

- The language of “searching” (Hebrew darash, “to search,” and its cognate midrash) was used in early tannaitic tradition and by Qumran scribes to refer to the straightforward meaning or interpretation of Scripture. In later talmudic tradition, midrash acquires something of a more technical meaning in distinction from peshat, i.e., the literal wooden sense.[↩]

- Cf. Jn 7:31–32, and the use of planáō in 7:12, 47. The recurring identification of Jesus as a “deceiver” (planós), in both Christian and rabbinic texts, indicates strongly that this was or was perceived to be a standard criticism leveled against Jesus and/or his followers. G. N. Stanton, “Early Christian-Jewish Polemic and Apologetic,” NTS 31 (1985): 381–82. See, e.g., Matt. 27:63; Justin Martyr Dial. 108; Acts of Thomas 48; T. Levi 16.3; b. Sanh 43a, 107b.[↩]

- Jesus makes similar kinds of arguments in Jn 5:17, 22, and 10:34. As Dodd notes, John’s Jesus here deploys the kinds of arguments used by those who may have opposed him or his followers. C. H. Dodd, The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 79.[↩]

- Here, Jesus corrects the verbs in the Hebrew (“gives” not “gave”) and the subject of the verb: God, not Moses.[↩]

- See N. A. Dahl, “The Johannine Church and History,” in The Interpretation of John, ed. John Ashton (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986), 127.[↩]

- John uses pisteúō 98 times (compare 11x in Matthew, 12x in Mark, and 9x in Luke), and designates Christians as “believers” (participle of pisteúō, not the adjectival form pistόs) 21 times (compare 4x in the Synoptics combined). Trebilco argues that, especially in Paul, Acts, and John, “believing” had become a far more significant “identifier” than in the Old Testament or in Second Temple Judaism. Paul Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 89; cf. 116.[↩]

- In his Proslogion, Anselm of Canterbury offered what has become a classic theological affirmation: “faith seeking understanding” (fides quaerens intellectum). In this, Anselm agreed with Augustine of Hippo, who observed similarly, “seek not to understand so that you may believe, but believe so that you may understand” (crede ut intelligas). This comment occurs, interestingly, in a comment on John 7:17 in his Tractates on the Gospel of John 29.6.[↩]

- Jn 1:18: “No one has ever seen God. The only [God], who is in the breast of the Father has expounded/interpreted (exēgēseto) him.”[↩]