Trevor Laurence

In the Bible, time is liturgical. The lights in the heavens are given to mark the appointed feasts of the Lord, sacred times for meeting with God.1 Israel’s calendar is organized around worship—cycles of work and rest, fasting and feasting, confession and cleansing, remembrance and rejoicing. These immersive rhythms continually rehearse God’s faithful works in history and choreograph communal life around communion with God, teaching Israel who she is before God and how she is to live before his face, embedding Israelite bodies and imaginations within a cosmos in which God’s gracious acts are determinative and entrance into his presence in worship is humanity’s chief end. Time, consequently, carries meaning; calendrical chronology is suffused with memory and expectation; and when something happens2 in the Bible may be as revelatory as what happens.

Indeed, God frequently acts in time to the rhythm he has set, utilizing chronological correspondence to help Israel and us discern the significance of his works. It is no coincidence that Israel crosses the Jordan into Canaan on the same day that she began preparation for the first Passover and the journey out of Egypt through the Red Sea:3 the crossing of the Jordan is a second exodus that brings to completion what was begun in the first. Accordingly, when God sees fit to tell us when an event occurs, we would do well to consider if that marking of time is intended to generate connections and communicate correlations.

The opening of Acts 2 is one such instance. “When the day of Pentecost arrived” (v. 1) introduces the account simply enough, but the time indicator links the events of Acts 2 with Israel’s liturgical time and God’s works in redemptive history, situating Christ’s giving of his Spirit within a network of associations that further reveal the meaning of what takes place in Jerusalem.

The Liturgy of Sinai

The day of Pentecost (Gr. πεντηκοστή, “fiftieth”) refers to Israel’s Feast of Weeks, which occurred “seven full weeks from the day after the Sabbath” (Lev 23:15) of Passover, “fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath” (Lev 23:16), and is thus rooted in a liturgical movement that begins with Passover.

In Leviticus 23, God proclaims that the fourteenth day of the first month is his Passover (v. 5), with the fifteenth day beginning the Feast of Unleavened Bread, a seven-day observance (vv. 6–8). The day after the Sabbath of the Passover week is the Feast of Firstfruits, celebrating the beginning of the harvest: “When you come into the land that I give you and reap its harvest, you shall bring the sheaf of the firstfruits of your harvest to the priest, and he shall wave the sheaf before the LORD, so that you may be accepted. On the day after the Sabbath the priest shall wave it” (vv. 10–11). And fifty days after the Feast of Firstfruits is the Feast of Weeks, marking the completion of the harvest with another holy convocation (vv. 15–22).

The timing of these feasts recapitulates the journey from Egypt to Sinai. In their captivity to Egypt, Israel observed the original Passover, journeyed to and through the Red Sea, and came to Sinai where they received God’s law roughly fifty days later (Exod 19:1–11). Israel’s liturgical calendar mirrors the movement of redemptive history: in their ritual life, they will celebrate the Passover, the firstfruits of the harvest, and the harvest’s culmination fifty days later.4 Why? Because the exodus is the beginning of a harvest that comes to completion at Sinai.

In the beginning, God plants a garden and brings up trees from the ground, and he brings Adam up from the ground5 and plants6 him in the garden with a commission to be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth with his seed.7 Adam is to grow up into a cultivated garden for God’s presence in the pattern of the garden of God’s presence he is called to cultivate.

After the blight of sin infects God’s garden, the seed of Abraham goes down into the soil of Egypt,8 and there grows into a great nation (cf. Gen 46:3): “the people of Israel were fruitful and increased greatly; they multiplied and grew exceedingly strong, so that the land was filled with them” (Exod 1:7; cf. Gen 1:28; Ps 80:9), ripe for a reaping. With the exodus, God commences the harvest of a people whom he purposes to plant like a garden on his sanctuary mountain (Exod 15:17), a harvest that is consummated around fifty days later at Sinai when God reveals his presence, gives his law, and constitutes Israel as the covenant nation with whom he will dwell. Once planted in the land that God will give, Israel is to be a new and holy Edenic garden-dwelling, a bountiful field, a fruit-bearing vineyard in whose midst God lives,9 the human expression of the arboreal imagery that ornamented the temple (1 Kgs 6–7), and the exodus-Sinai event is God’s harvest of a garden-people for his presence from firstfruits to final gathering. The Feasts of Firstfruits and Weeks, set as they are in liturgical time, together celebrate Israel’s harvest of her fruitful fields in the land of God’s presence and God’s harvest of Israel out of Egypt to be a fruitful field for his presence, the vineyard-garden where he reigns and resides.

Rather wondrously, these thematic associations with Israel’s liturgical calendar emerge in the New Testament as well, particularly in the events surrounding Jesus’ dying and rising. Jesus celebrates the Passover and goes to the cross as the lamb whose blood covers his people, delivering from judgment. On the day after the Sabbath of Passover—Sunday, the Feast of Firstfruits—Jesus makes his exodus out of the grave in resurrection life (Luke 9:31), raised from the bondage of death as “the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep” (1 Cor 15:20).10 And fifty days later, having ascended into the presence of God, from his throne on high Jesus gives the Spirit who writes God’s law on the hearts of men, constitutes his new covenant community, and harvests a people for his holy presence—a vineyard that will abide in the true vine (John 15:5), a garden-temple for God’s dwelling (1 Cor 3:9) who will bear the Spirit’s fruit of holiness and fill the earth.

Christ’s giving of his Spirit at Pentecost is a new Sinai event that completes the movement of his exodus-resurrection, a harvest of a new humanity in Jesus the firstfruits to be the garden people with and within whom God makes his residence.

Sinai in Jerusalem

With the lens stimulated by the timing of Acts 2 in place, the range of events at Pentecost comes more clearly into focus as the fulfillment and surpassing of Sinai.

Moses led God’s people through the waters of judgment into freedom, releasing Israel from the oppressive powers that enslaved her. While Israel waited below, Moses ascended Mt. Sinai and “went up to God” (Exod 19:3). There, the Lord revealed his theophanic presence in the sight of all the people (Exod 19:11) with a thick cloud and the loud sound of thunder and trumpet, descending in fire and wrapping the mountain in smoke (Exod 19:16–18). Atop Sinai, Moses saw a pattern of the tabernacle11—Sinai was a model temple mount—and God’s presence in the glory cloud which descended upon Sinai would eventually rest over and fill the tabernacle (Exod 40:34–38; Num 9:15–18) and take up permanent residence in the temple (1 Kgs 8:10–11), in both cases driving out the priestly ministers with his glory.

At Sinai, God gave Israel his law, establishing her as a holy nation and royal priesthood under his kingship (Exod 19:6). Of course, Israel quickly descended into idolatry, rebelling against God’s covenant word, and Moses appealed to the Abrahamic promise in intercession so that the Lord would relent from consuming them in his wrath (Exod 32:13–14). Nevertheless, when Moses came down from Sinai and saw that the people had broken loose “to the derision of their enemies” (Exod 32:25), the Levites answered his call for judgment within Israel—cutting 3000 men with the sword—and were set apart as priests (Exod 32:27–29).

And these are in many respects the contours of the story of Pentecost.

Jesus leads God’s people through the waters of judgment into freedom through his death and resurrection, releasing them from the oppressive powers that enslaved them. While the new Israel whom he had gathered around himself waits below, Jesus ascends the heavenly Zion and goes up to God (Acts 1:9–11). Fifty days after Christ’s exodus, the Lord reveals his theophanic presence in the sight of all with “a sound like a mighty rushing wind” (Acts 2:2) that fills the entire house and “divided tongues as of fire” (Acts 2:3) that appear and rest on each person there, descending in cloud and flame. The mountain-top pattern of the tabernacle is realized in the church: God’s presence in the glory-cloud which descended upon Sinai now rests over and fills every disciple of Jesus (Acts 2:4), taking up permanent residence in the temple that is his people, and in this case, his priestly ministers are indwelt with—not driven out by—God’s glory.

Jesus gives the Spirit who writes God’s law on the heart, reuniting the scattered nation of Israel (Acts 2:5; cf. Ezek 37:15–28) under his messianic kingship,12 anointing them with his Holy Spirit as his holy nation and royal priesthood.13 At this Sinai event, however, many receive God’s covenant word (Acts 2:41) as Peter appeals to the Abrahamic promise and announces a forgiveness in Jesus that saves from the consuming wrath of God (Acts 2:38–39). And rather than the judgment of swords in flesh, those gathered at Pentecost are “cut to the heart” (Acts 2:37) with the word of Christ; 3000 die and rise in faith and baptism (Acts 2:41), washed and consecrated as priests of God; and this new community receives not derision but “favor with all the people” (Acts 2:47).

Recounting God’s entrance into his temple at Zion, Ps 68:17 proclaims, “Sinai is now in the sanctuary.” Recounting God’s entrance into his temple-people at Jerusalem, Acts 2 declares, “Sinai is now in the saints.”

The Tower and the Temple

It is difficult to miss echoes of Babel in the Pentecost narrative. In Gen 11, a humanity united in rebellion is scattered when God comes down, multiplies their language, and confuses their speech so that they cannot understand. In Acts 2, a humanity from among the scattered nations is united in faith when God comes down and uses multiplied languages so that they can understand the gospel, stimulating a confusion that gives way to astonishment and curiosity and, finally, repentance.14

But appreciation of the rumblings of Sinai in Acts 2 discloses a more fundamental, indeed a more beautiful, coherence between Babel and Pentecost.

The tower of Babel is built to have “its top in the heavens” (Gen 11:4), to connect heaven and earth, the dwelling places of God and men. Babel’s tower is an idolatrous high place, a false attempt to ascend into God’s presence, a counterfeit temple, a man-made “mountain of God.”15 Intended to manufacture a place for God’s presence on earth, Babel is a pseudo-Eden, a pseudo-Sinai, a pseudo-Zion. And its perversity is magnified by the fact that, while God’s temple is the place of worship where he makes his name dwell (Deut 12:5, 11; 1 Kgs 8:16, 29; 9:3), Babel is an exercise in self-worship whose end is to “make a name for ourselves” (Gen 11:4).

Pentecost is the reversal of Babel, yes, but not merely because scattered peoples are united and multiplied languages yield understanding. More basic than that, Pentecost is the reversal of Babel because it is Sinai’s fulfillment rather than Sinai’s forgery. Where Babel seeks to attain God’s presence as an imitation holy mountain, Pentecost is the gift of the very presence that descended upon God’s holy mountain poured into the hearts of his people. Babel strives in vain to be a man-made temple of God—a temple-building project concocted by the “children of man” (Gen 11:5)—and God comes down in judgment to stop them from making their name. Pentecost is the gracious inauguration of a God-made temple of men—a temple-building project whose raw material is the children of God—and God comes down in blessing to make them the dwelling place for his name.

“When the Day of Pentecost Arrived…”

“When the day of Pentecost arrived, they were all together in one place” (Acts 2:1). In Jerusalem on the Feast of Weeks, on a day charged with the memory and significance of liturgical time, God continued and culminated the very work which the day of Pentecost celebrated. On the festival of God’s Sinai-harvest, those gathered together in Jerusalem would be swept up into a consummating recapitulation of Sinai, harvested to be God’s garden-people, the holy vineyard for his holy dwelling. Fifty days on from Christ’s firstfruits resurrection, they would be filled with God’s glory-Spirit, made into the temple-mountain where God’s presence abides16—the fulfillment of Sinai’s hope, the substance of Babel’s pale dream.

Trevor Laurence is the Executive Director of the Cateclesia Institute and the author of Cursing with God: The Imprecatory Psalms and the Ethics of Christian Prayer (Baylor University Press, 2022).

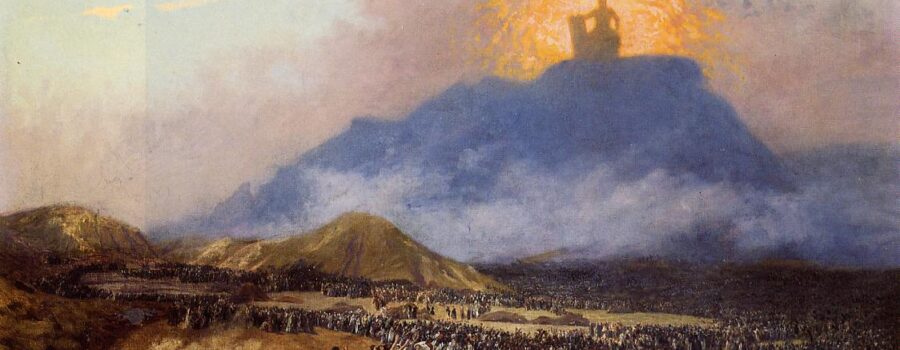

Image: Jean-Leon Gerome, Moses on Mount Sinai

- Cp. Gen 1:14 with Lev 23:2.[↩]

- As well as how long it happens.[↩]

- The tenth day of the first month. See Josh 4:19; Exod 12:3[↩]

- On the association of the Feast of Weeks with the events of Sinai, cf. F. F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, NICNT (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1988, rev.), 49–50; L. Michael Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord?: A Biblical Theology of the Book of Leviticus, NSBT 37 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 35; G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God, NSBT 17 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 204.[↩]

- The phrase מִן־הָאַדָמָה is repeated in vv. 7, 9 of Adam and the trees of the garden, suggesting deliberate correspondence.[↩]

- The verb שִׂים (frequently translated “placed” or “put” in Gen 2:8) can have agricultural connotations, as in Isa 28:25.[↩]

- Cf. the suggestion of James B. Jordan, Through New Eyes: Developing a Biblical View of the World (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1988), 90.[↩]

- Note the spatial orientation of the Bible’s descriptions of Egypt: God’s people go “down to Egypt” (e.g., Gen 12:10) and come “up out of Egypt” (e.g., Gen 45:25), like going down into the grave and rising up in resurrection, like going down into the earth a seed and rising up in budding life (cf. 1 Cor 15:36–38).[↩]

- Cf. the abundant agricultural imagery used to describe Israel in, e.g., Num 24:6; Isa 5:1–7; 27:2–6; 61:3; Pss 1:3; 72:16; 144:12; Jer 2:3, 21; Hos 14:5–8; Amos 9:15. Of particular note is the narration of Ps 80:8–9:

You brought a vine out of Egypt;

you drove out the nations and planted it.

You cleared the ground for it;

it took deep root and filled the land.

This is the language of harvest and trans-plant. The flip-side of this imagery is manifest in the regular descriptions of the wicked as chaff, thorns, vegetation that impedes fruitfulness and must be cleared away.[↩] - And note that Paul’s reference to Christ as the firstfruits shortly gives way to the agricultural imagery of seeds being sown and rising in new life in vv. 36–38.[↩]

- E.g., Exod 25:9, 40. Indeed, Sinai was not only the place where God disclosed the pattern of the tabernacle; it was itself a pattern of the tabernacle, divided into three zones of increasing holiness, the most holy of which—the place of God’s presence—could only be accessed by a singular priestly mediator. On this, see Mary Douglas, Leviticus as Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 59–65.[↩]

- Notice that the focus of Acts 2:5 is on the presence of Jews from every nation under heaven. This is the anticipated eschatological regathering of Israel under the Davidic shepherd-king. See Alan J. Thompson, The Acts of the Risen Lord Jesus: Luke’s Account of God’s Unfolding Plan, NSBT 27 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011), 109–12.[↩]

- It is no wonder that Peter, before whose eyes the fulfillment of Sinai unfolded, takes up the descriptors given at Sinai and applies them to the church in 1 Pet 2:9.[↩]

- Interestingly, the term used to describe the multitude’s bewilderment in Acts 2:6 (συγχέω) is the same term used to describe the people’s confusion at Babel in LXX Gen 11:7, 9.[↩]

- Morales, Who Shall Ascend, 62; cf. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission, 102.[↩]

- After all, Jesus did tell his followers they are a city set on a hill (Matt 5:14), Zion atop God’s mountain.[↩]