James Bejon

Why do biblical narratives contain so many common motifs?

Take the exodus. The exodus is both a motif which is repeated and itself a repeat. As Alastair Roberts and Andrew Wilson point out,1 long before the exodus takes place, Noah is “remembered” and delivered from a generation worthy of judgment through the watery wrath of God and is later brought out onto a mountain top, where God enters into a covenant with him. Afterwards, due to a famine in the land of Canaan, Abraham heads down to Egypt, where Pharaoh is plagued, which causes Abraham and his people (enriched by its wealth) to be expelled from Egypt. And, before too long, Lot is rescued from a land under judgment in the middle of the night (urged on by the Pharaoh-esque cry, קוּמוּ צְּאוּ = “Arise! Get out!”)2 when unleavened bread has just been baked.

Explaining Biblical Repetition

All of these events significantly predate the (Mosaic) exodus, yet they clearly prefigure its general shape and nature. Why? How are we to explain their many commonalities?

The most commonly proffered explanations are twofold:

Option #1: the use and re-use of common source material (Gunkel, Noth, von Rad, etc.).

Option #2: the use of common literary conventions, also known as “type-scenes” (Alter).3

Alter’s description of Option #2 bears reproduction in full, since it helpfully distinguishes Option #2 from Option #1, both in terms of nature and motivation:

Let us suppose that, some centuries hence, only a dozen films survive from the whole corpus of Hollywood westerns. As students of 20th cent. cinema (screening the films on an ingeniously reconstructed archaic projector), we notice a recurrent peculiarity: in eleven of the films, the sheriff-hero has the same anomalous neurological trait of hyper-reflexivity: no matter the situation in which his adversaries confront him, he is always able to pull his gun out of its holster and fire before they, with their weapons poised, can pull the trigger. In the twelfth film, the sheriff has a withered arm and, instead of a six-shooter, he uses a rifle which he carries slung over his back.

Now, [the existence of] eleven hyper-reflexive sheriffs [is] utterly improbable by any realistic standards—though one scholar will no doubt propose that, in the Old West, the function of the sheriff was generally filled by members of a hereditary caste that in fact had this genetic trait. The scholars will then divide between a majority who posit an original source-western…imperfectly reproduced in a whole series of later versions…and a more speculative minority who propose an old California Indian myth concerning a sky-god with arms of lightning, of which all these films are scrambled and diluted secular adaptations. The twelfth film, in the view of both schools, must be ascribed to a different cinematic tradition.

The central point, of course, that these strictly historical hypotheses would fail even to touch upon is the presence of convention. We contemporary viewers of westerns back in the era when the films were made immediately recognize the convention without having to name it as such. Much of our pleasure in watching westerns derives from our awareness that the hero, however sinister the dangers looming over him, leads a charmed life, …and the familiar token of his indomitable manhood is his invariably, often uncanny, quickness on the draw.

For us, the recurrence of the hyper-reflexive sheriff is not an enigma to be explained, but…a necessary condition for telling a western story in the film medium as it should be told. With our easy knowledge of the convention, moreover, we naturally see a point in the twelfth exceptional film which would be invisible to the historical scholars. For in this case, we recognize that the convention of the quick-drawing hero is present through its deliberate suppression. Here is a sheriff who seems to lack the expected equipment for his role, but we note the daring assertion of manly will against almost impossible odds in the hero’s learning to make do with what he has…4

For Alter, then, repetition in the biblical narratives is to be explained not by the use and reuse of a common source, but by the existence of literary norms and conventions, which could potentially function in a variety of ways, all of which is well and good. But, in both cases, the fidelity of the biblical narrative to the facts of history is compromised, on the one hand because of the way in which sources are reworked and re-invented, and on the other hand because of the tendency of ancient writers to conform the facts of history to literary norms and conventions.

In this article, I want to propose an explanation for the repetition inherent in the biblical narrative which does not compromise its fidelity to the facts of history.

My proposal consists (very roughly) of a dash of Option #1, a slug of Option #2, a healthy measure of skepticism about man’s autonomy, and a firm belief in God’s sovereignty and artistry.

Patterns in Scripture, Patterns in History

More precisely, my proposal can be expanded as follows.

Much of what is recorded in Scripture may indeed—per the assertion of Option #1—have leaned on source material (oral or otherwise, e.g., “the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel”). And these sources may have exhibited commonalities, especially if they included forms such as Psalms, other songs (e.g., those recorded in Exod 15, Judg 5, etc.), “liturgy,” and so forth.

At the same time, I do not doubt the authors of Scripture were influenced—per the assertion of Option #2—by literary conventions, most notably (whether consciously or unconsciously) those established by Scripture itself. Authors wrote against the backdrop of the shape, fabric, and nature of Israel’s story as it was recorded in extant Scripture (and remembered in other ways). And many of them no doubt composed their texts so as to resonate with and contrast with specific parts of that story. Roberts and Wilson helpfully put the point in musical terms.5 For them, Alter’s type-scene is the equivalent of a harmony or motif introduced at the start of a piece of music, which is later recapitulated (sometimes in part, sometimes in full, sometimes against one backdrop, sometimes against another), developed, reworked, and much more.

The refrain of motifs in Scripture may, therefore, have a literary and/or cultural explanation. But, of course, our desire to understand such features of the biblical narrative needn’t be restricted to literary considerations. As believers in a sovereign God, we can supplement—and/or undergird—the above explanations by additional, deeper explanations. For instance:

• History often repeats itself, and truth is sometimes stranger than fiction.

• People are predictable. We are all to some extent the products of our pasts, and we often repeat the same mistakes, while certain patterns of behaviour are clearly a recipe for success.

• And, of course, for the Christian, beyond and beneath both of these issues lies a theological consideration. God often works in consistent ways and predictable patterns, not least because it allows us to better comprehend his word and world. For the God who is the author of history, repetition in history and literary type-scenes are one and the same.

In Scripture, then, intertextuality is not mere intertextuality. Or, to put the point another way (as a colleague on Twitter who summarized my idea helpfully did),6 typology is a feature of history before it is a feature of the biblical narrative. Biblical writers write typologically because God has ordained and written history typologically, and biblical interpreters should interpret the Bible typologically because it reflects the mind of history’s author.

As I say, I do not proffer that explanation as necessary (though, as a Christian, I happen to think it is the correct explanation). I simply proffer it as a way to explain the repetition inherent in the biblical narrative which 1) explains the relevant evidence as well as its alternatives, and 2) does so without any compromise of the historicity of the biblical narrative.

An additional feature of my explanation is its ability to explain how prophetic literature can remain relevant to God’s people over time. Consider, by way of illustration, Peter Leithart’s summary and assessment of different approaches to the book of Revelation:

“Idealism” is a coherent, plausible, and venerable method for interpreting the symbols and types of Revelation. It is not, however, consistent with the way biblical poetry works. Isaiah describes Jerusalem, not some generic city of man, as Sodom. . . .Daniel sees beasts coming from the sea, and the beasts are identifiable kingdoms (with some qualifications, Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome). Daniel sees a goat racing over the land without touching the ground. It crashes into a ram with two horns and shatters the ram’s horns (Dan 8:5–8). That is not a generic portrait of “conquest.” It is Alexander’s conquest of the Persians. We can tease out generalized abstracted types from the historical referents: the goat is Alexander, but other fast-moving empires have appeared in history (e.g., Hitler the speeding goat who shatters the horns of Poland and France), and we can and must extend the biblical imagery to assess and evaluate them. There will be other cities like the Babylon of Revelation, and they will display some of the same features which John sees in the city and, importantly, meet the same fate. But John is not referring to those other cities, nor to some transcendent concept or class of “harlot city” of which there are many specific instances. He refers to a real harlot city, one which existed in his own time, and that harlot city becomes a type of future cities.

All this is a way of saying that John is a typologist rather than an allegorist. It is an admittedly crude distinction, rightly disputed by many scholars. Whether or not the terms are felicitous, there is a genuine distinction between a mode of reading which moves from text to an abstract, generalized concept (what I am calling allegory) as opposed to one that moves from text to real-life referent, while leaving open the prospect that mimics of the real-world referent will emerge, non-identically, in other times and places (typology). There are allegorical passages in Revelation (e.g., 12:1–6), but even these do not refer to concepts, but to persons and events. And then these meaningful events foreshadow later events, not in every respect but in general.

Thomas Aquinas was on the right track: the words on the pages of Scripture have a literal meaning, referring in the main to people who actually existed and events that actually took place; the spiritual, typological meanings of Scripture arise from the events to which the words refer. God can write with events and people and things as well as words, and the pattern of history itself is meaningful, full of foreshadowings, ironies, repetitions, analogies. These are not literary devices imposed on history, but the very fabric of history. Abstraction is not the first moment of interpretation, but a later one.7

Hence, to convert Leithart’s sentiments to the matter at hand, biblical narrative is repetitive for the same reason biblical prophecy is relevant: because history follows predictable divinely-ordained patterns.

The Regularity of God’s Handiwork

As students of Scripture, it is important for us to distinguish datapoints from explanations. The datapoints behind the theories of form critics (such as Gunkel, Noth, von Rad) and literary critics (such as Alter) are unobjectionable. The biblical narrative involves many key themes and motifs. But how should these datapoints be explained?

That is where the form critics and literary critics part company, and that is where I have sought to propose a third way. The repetition inherent in the biblical narrative, I submit, is neither the result of a common literary source, nor of a common literary convention, but is fundamentally a reflection of the regularity of God’s handiwork in his great masterpiece—world history.

James Bejon is a junior researcher at Tyndale House in Cambridge, United Kingdom. You can follow him on Twitter.

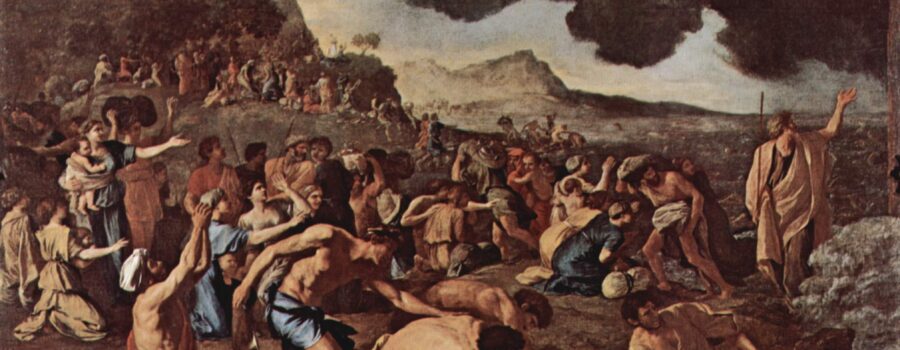

Image: Nicolas Poussin, The Crossing of the Red Sea

- Alastair J. Roberts and Andrew Wilson, Echoes of Exodus: Tracing Themes of Redemption through Scripture (Wheaton: Crossway, 2018).[↩]

- Cp. Gen 19:14 with Exod 12:31.[↩]

- Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 56–57.[↩]

- Ibid., 56–57.[↩]

- See their Echoes of Exodus.[↩]

- Thank you, Joe Rigney![↩]

- Peter J. Leithart, Revelation 1–11, ITC (New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2018), 12–13.[↩]